The exhibition of painting by Louise Hearman must be seen in the light of the artist's recent successes as winner of the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize in 2014 and Archibald Prize in 2016. The exhibition, curated by Anna Davis for Sydney's Museum of Contemporary Art, does not show Hearman as a super-realist painter, which the two prize-winning portraits might suggest. Instead it supports the existing view of Hearman as a solid practitioner committed to paint with an idiosyncratic take on realism. The two recent prizes may have given Hearman a certain prominence in the media, but the exhibition does not infer that Hearman is an overlooked artist whose genius has been ignored. Indeed, the singularity of Hearman's work makes her difficult to classify: she comes across as eccentric and independent of any group or movement.

Hearman has been on the radar since she started painting in the late 1980s with permission from postmodernism and neo-expressionism to use the figure. Indeed, it is hard to imagine Hearman ignoring her acute observational and rendering skills to attempt anything else. In the last two decades painting took a gracious retirement from art schools in seeming response to pressure from generational upstarts photography and anything digital that offered more contemporary and efficient modes of image making. Few were willing to totally write off painting, American critic Dave Hickey noting a few years ago that “Painting isn't dead except as a major art. From now on it will be a discourse of adepts, like Jazz.” Lazarus-like, painting certainly seems to be enjoying a current vogue.

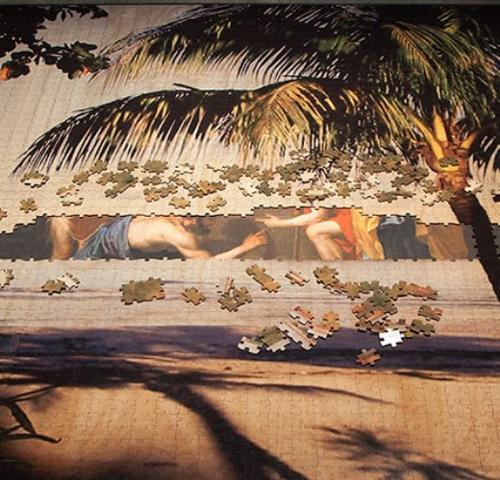

Image courtesy and © the artist. Photo: Mark Ashkanasy

The Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in Melbourne recently mounted a mammoth two-part exhibition, Painting More Painting (29 July – 25 September 2016), and The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World (14 December 2014 – 5 April 2015) at New York's MOMA, is their first painting show in over a decade. The world is seeing soaring art prices and booming art fairs selling—what else?—painting. Painters have adapted to the new technology as an economic means of note-taking and sales. The zombie formalists, for example, were accused of making paintings to match the format of phone screens so as to facilitate easy viewing and sales as quick as bet on a smart phone. The flat format of a painting is sympathetic to digital imaging and online sales. And crusty paint looks appropriately artisan, singular and handmade as to take on a Portlandia chic.

Hearman's works are painterly, yet precisely modelled in accurate tones and perspective that convince as realistic. She favours certain subjects: spooky girls, anonymous roads, endearing but often knowing pets and dark landscapes, all inevitably shown in crepuscular light. This half light suggests a time of transience: these are moments and places “in between”. Not that the images look hallucinogenic; it seems to me that Hearman pictures notions of possibility, of remembrance and dream. Is there any other way to explain the juxtaposition of an aircraft wing and a cat head? Or a child's head emerging from clouds? Hearman's illogical combinations seem to lack the implicit metaphor or symbolism of surrealism. Her images can be awkward at times, despite the seductive materiality of the paint.

Hearman claims “teeth, hair, light” as constants in her work, but also feet, when they touch the ground (despite her fascination with disembodied heads) and equally admires the way trees are rooted to ground—the join of organic to earth. While there are things she loves to paint often—and teeth, hair, light allow her to enjoy her manifest paint handling talent—her subjects are often things she stumbles over. A face on the street, light glancing off water, the movement of clouds and found portraits. It's often something small that grabs the artist. The paintings suggest that her own puzzlement is the driver in some ways for making pictures, that to see and record is to understand. The world around us is in constant flux but there are moments when things, momentarily, seem clear, and the ambiguity and transitional offer insight into reality below the surface. Like mystic William Blake, Hearman seems able “to see a World in a Grain of Sand and a Heaven in a Wild Flower”. Despite the perception that Hearman's images are unworldly, there is an uneasy but genuine relationship to the world. She strives for an “ecstatic normal”, although her closeness to nature is mediated by the camera.

The exhibition seems intended to highlight Hearman’s technique, the physicality and alchemy of paint. Why else would curator Anna Davis include the artist's palette of piled up colours in the display except to create an amazement at the before and after of transformation. The transformation of coloured mud to recognisable imagery is indeed magical but so is Hearman's bending that technique to conceptual ends in the transformation of the ordinary into things that are somehow “special”—the aura of the moment, the recognition of something that matters, despite it being unseen and unknown. Her enterprise seems like a campaign to hold a moment and rebuild a sensation that she feels holds meaning. This is meaning, not at a high philosophical level but at a bodily level. This is what nature tells you and what your biology informs you, intuitively. Looking at the exhibition I hear the hum of white light at midday, the bass notes of dusk, the ticking clockwork of the heart, singled out and made special by virtue of being painted.

Critics and writers have compared Hearman with Francisco Goya, perhaps with the notion that the early nineteenth-century artist painted dark pictures with a psychological twist. But, technically, Hearman is more likely channelling the solid workmanship and prosaic perspective of Gustave Courbet. Hearman appears fond of nineteenth-century academic art, which revels in technical pyrotechnics and, despite its brazen insincerity, suggests a faith in the images of the mind that we nominate as art. Her references are, in any case, not really art and most work appears to cite the concreteness of the filmic or photographic world. Hearman's compositions are routinely simple, usually with a single and central focus.

Her relationship with photography is interesting. Clearly her images derive from photographs evident in their lighting, tonal rendering and compositions, but the artist adjusts and changes things. Sometimes it's the luminosity (making her portrait heads spectral), although more often it's the addition of new and incongruent elements. This can make her worst work look like carefully painted Photoshop images. In her best works, Hearman seems to regard photographs as notes, initial representations that have only surface and serve as source material for a more nuanced and layered painting. Hearman acts as if painting has ultimate authority, a flattering concept for art lovers and collectors.

Hearman's painted constructions admit the artifice and, like Victorian melodrama, the viewer is complicit in the sensation. Much as when the magician pulls a rabbit out of a hat, the artist pulls a rabbit out of a landscape or a cat from a cloud, and the viewer knows it's not real but enjoys the pretence of innocence and the sophistication of seeing through it. The sensation of real life terror that might accompany loss of control or panic and can be enjoyable when played out as the faux horror of Grand, or in Hearman's case, petite Guignol within the safety of the gallery. It's a gentle, albeit enigmatic, world she draws, evoking dark emotions without serving gore. Hearman is willing to appear naïf in admitting to believe in beauty and who would want to burst that bubble?

Hearman's work somehow suggests genuine conviction despite conjuring up the clichés of emotional porn in her mix of spiritual little girls, adorable pets, vermillion sunsets, purple dusks and wooded landscapes. She is very much the artist's artist in her fascination with the properties of paint and hermetic personal vision. There is also an enduring fascination for such small scale, domestic-sized pictures that offer the satisfaction of lush painted surfaces and a belief in the artist's insight.

This exhibition is perhaps a fork in the road for this artist. She has been painting solidly and exhibiting regularly for three decades with remarkable constancy. Her subjects might change—favouring pets, landscapes, or portraits—and the medium might occasionally include pastels but Hearman's investment in her notable technical ability has not prompted a change in style or theme. Her recent successes in the Doug Moran and Archibald prizes with highly detailed portraits emphasising the meatiness and decay of human flesh, might tempt Hearman to lean further to an increasingly visceral realism and possibly an exclusive focus on portraiture. I suspect this won't happen. I would like to see more complex compositions and a greater engagement with metaphor but Hearman is an artist who has always gone her own way.