Simryn Gill is well known for her subtle process-driven work investigating time, memory and place. These themes return in her new exhibition, Sweet Chariot currently showing at Griffith University Art Gallery in Brisbane. Curated by Naomi Evans, this subtle and evocative show is comprised of three visually distinct, but thematically interrelated series. The first is an older sculptural work, Four Atlases Of The World And One Of Stars (2009), located at the gallery’s entrance. The five atlases are material, tactile balls created from scraps of paper. On closer inspection, place names present themselves, vestiges of the maps from which they were selected. By returning the flat map to the sphere, Gill evokes the ancient iconography of the Titan god, Atlas. Condemned and exiled by Zeus for his treachery, the five spherical globes remind us of the task assigned to Atlas: to carry heaven on his shoulders for eternity.

Much later, Atlas became associated with cartography or the study and production of maps. An atlas is a useful entry point and reflects the pertinence of geography and navigation as continuing themes in Gill’s work. Unlike a book, we do not read an atlas from beginning to end. Instead, its entry point is random. As described by French philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman, an atlas is open to possibilities, and lays no claim to the finitude of the archive or encyclopaedia. An atlas is a tool that lends itself to browsing and following unforeseen and unexpected pathways. It is particularly well suited to creating chains of associations that do not conform to pre-existing axioms. Didi-Huberman describes the atlas as best suited for “the inexhaustible opening up to possibilities that are not yet given”.[1]

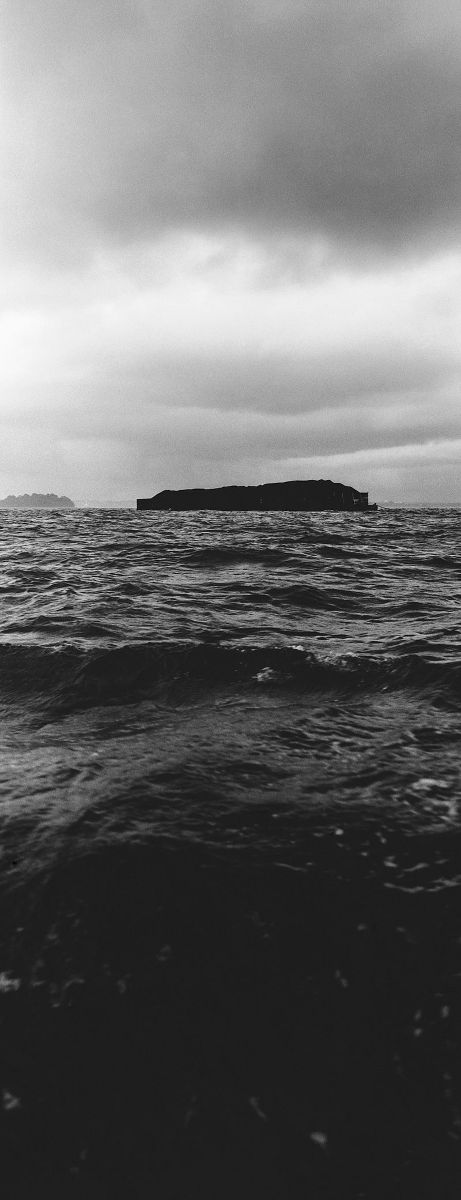

This evocative chain of associations Didi-Huberman speaks of allows for gentle conversations between the images to emerge. The second series Sweet Chariot (2015) is a sequence of vertical black and white photographs taken by the artist from a small fishing boat in the Strait of Malacca. Reflecting Gill’s interest in cartography, this narrow stretch of water is one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. As the major shipping artery between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, the Strait of Malacca is critical for global trade networks and the economies of Southeast Asia. The vertical photographs simultaneously point to notions of migration and relocation, reinforced by the series title, “Swing low, sweet chariot”. As a song connected with African American slavery, the images gently evoke the subjugation of geographically displaced peoples.

The final series of relief prints Pressing In (2016) are imprints created from found timber refuse washed up on the Malaysian coast. Gill’s long-term interest in collecting and reusing materials comes to the fore. The machine-shaped timber was collected by Gill from the beach was machine-made waste. The object speaks of its own history here; its previous lives, travels, indentations and imperfections, and eventual material decay. Timber decomposes rapidly in the tropics, accelerated by its time in the water. Developed with Melbourne printmaker Trent Walter, the prints have been made onto an eclectic collection of found paper materials including graph paper, records of pay rolls, navigational logs and charts. Like the timber used to make the prints, the paper is fragile and unstable, impermanent and subject to the corrosive effects of time and light. Time embeds itself in the prints as a visible sign of entropy and decay.

As a straight line, the horizon betrays the actual curvature of the earth’s surface. Horizons are simultaneously present and absent, stationary and mobile. The entire exhibition is organised around a paradoxically real and imagined horizon emanating from the photographs and can be traced along the gallery’s walls in full circle, enveloping the spectator. Situated roughly at eye level, the horizon asserts itself as a visual filament, uniting the series of photographs and prints. If the horizon may be thought of as a positive in the photographic series, a clear demarcation between ocean and sky, it is a negative in the prints. Not quite identical mirrors of the same, the printed shapes float toward a horizontal gap or space, evoking a negative or absent horizon.

.jpg)

Juxtaposed against the strength of the horizon is the vertical thrust created by the repetition of the vertical prints and photographs. The gallery space pulses with the competitive tension created by the horizon’s strength and the upward momentum created by the vertical shapes. The prints are grouped together in clusters of three or four, akin to small groupings of trees, reaching toward the sky. The emphasis on the upright is reinforced by the shapes of the prints themselves as Gill summons the ascendant forms pursued by her modernist ancestors, such as Constantin Brâncuși’s Bird in Space (1923) and Kazimir Malevich’s series of abstract shapes floating in space from 1915. The push and pull of the vertical and horizontal serves to insert the spectator into the grid as the map’s logic extends to the actual installation of the work in the gallery space.

Gill’s palette is sombre and organic, offset by the blue tones of the gallery walls. Deliberately eschewing narrative closure, works from the series whisper to each other, delivering alternative, unforeseen exchanges. Gill’s position on the fishing boat evokes further connections with the flimsy leaky boats used by asylum seekers. Underscored by the dark and ominous mood created by the photographs, I begin to consider the history of the found timber fragments used to make the prints. What is the timber’s origin? Could it be from the fragile boats used by people smugglers that did not reach their transit destination of Indonesia? The invisibility of displaced people begins to permeate the exhibition, as the waterway between Sumatra and Malaysia subtly shifts from trade route to menacing watery grave.

If maps reduce the complexity of the world to a flat image, Gill seeks to restore this complexity, albeit in its fragmented and torn form. Gill’s practice has always been concerned with notions of place. As the first exhibition of her work in five years by an Australian public institution, Sweet Chariot is a welcome and important update on this theme, delicately shifting from the personal to the political.

Footnotes

- ^ Georges Didi-Huberman, Atlas: How to Carry The World On One’s Back?, exhibition catalogue, Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2011, p. 15.