The defining characteristic of the Next Wave Festival is its emphasis on peripheral and emerging practices. Under the guidance of artistic director Georgie Meagher, notions of friction and affinity, co-existence and conversation and an interest in the possibilities of science fiction were explored by contrasting voices across dance, theatre, visual art and music. From the bio-erotica of Ecosexual Bathhouse by Pony Express to Amrita Hepi and Jahra Wasasala’s affecting dance work Passing and Rani Pramesti’s confronting Sedih // Sunno, the appeal of the festival is the variety of cultural experiences on offer in the program and coming across new works that ring true. It’s exciting to see artists take chances – something that Next Wave should be commended for cultivating.

The festival provides a forum for challenging and sometimes uncomfortable new work. I was apprehensive about going to see Sedih // Sunno by Rani P. Collaborations. On the morning of the performance, I heard the lead artist Rani Pramesti on the radio discussing the subject of child sexual abuse. I prepared myself for a confronting experience. But I’m glad I went – Sedih // Sunno, performed at North Melbourne’s Arts House was one of the best works I saw during the festival. It was upsetting at times, but also disarmingly funny and moving. Described in the program as a “gentle invitation to listen to sadness” (Sedih is Bahasa Indonesian for “sadness”, and Sunno is Fijian Hindi for “listen”), Sedih // Sunno sees Pramesti and her collaborators Ria Soemardjo, Kei Murakami and Shivanjani Lal guide a small audience of twelve through a series of domestic scenes.

Inspired by an assertion of her mother’s that “in sadness, you are always alone”, Pramesti uses family heirlooms, audio recordings and personal anecdotes in an attempt to question that assertion, and reflect on her mother’s experience of sexual abuse. Taking care not to speak on behalf of her mother, Pramesti plays audio recordings of their conversations, allowing her mother’s voice to be the one recounting her past. While in the first part of Sedih // Sunno we are introduced to trauma, in the second we are encouraged to experience the giddy innocence of children’s games, and in the third to reflect on the possibility of reconciliation. At one point, Pramesti explains the process of making Indonesian Batik. Using hot wax, at pattern is drawn or stamped onto a piece of fabric before it is dyed and the wax removed with hot water, repeated over until the Batik is finished. As studied and collected by her mother, Batik symbolised the cumulative effects of life experience mirrored in the traces and marks left behind.

In a completely different approach to history, Daniel Jenatsch’s video-opera A-97 at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image imagines a historical glitch in which the year 1997 isn’t over. With the inventive use of a green screen and live video footage, Jenastch’s narrative twists and diverts around Angela N, a member of an underground historical society who is trapped in 1997 by a malfunctioning IBM computer identifying as the Russian chess champion Garry Kasparov. Emulating the layered postmodern densities and complexities of key works by writers published that year – including Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon and David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (late 1996), A-97 flits between Mesopotamian spirituality, Arctic soundwaves, Pauline Hanson, Jean Baudrillard and Next Wave’s own website to carry the story. At one point, Angela N. is calmly told to imagine her thoughts to be like icebergs struck by lightning and broken into melting fragments that become part of a larger body of water. In A-97, the narrative is similarly broken into fragments that can, like ice on water, become part of something more, but also unrecognisable and forgotten.

In her installation Decolonist presented at West Space in Melbourne’s CBD, Katie West fosters slowness and reflection on Australia’s colonial history. The room is separated in two by a large, lightly dyed white piece of hanging fabric and in a scale comparable to the rectangular pocket for the Union Jack on the Australian flag, a video is projected onto the upper corner of the partition as another “Decolonist Flag” hangs over an arrangement of native plants. While the video displays a Venn diagram with a black centre over mirrored footage of bushland, West’s voice calmly describes a process of breathing, walking through a landscape, recognising trauma, meditating through it and moving forward. Decolonist suggests a middle-ground in which those who have reaped the benefits of colonisation and those still dealing with its trauma can meet through a method of decolonisation.

In a recent article in The Guardian, West describes the difficulty of identifying with her Yindjibarndi culture in a country marked by the assimilation policies implemented by the colonisers to stamp out Indigenous cultures. West cites her refusal to think of her identity as inauthentic, and her practice as a process of undoing anxiety. When collecting gum leaves and blossoms, or dying fabric with eucalyptus bark to create her work, she reflects that “In these moments of uncomplicated contemplation I simply exist. I have no trauma. I have no anxiety”.[1] In Decolonist, West re-creates a contemplative space in which to reflect on Australian history, proposing a method in which we might “slowly unlearn what we have been taught”.

Extending these themes, The Fraud Complex exhibited over two other rooms at West Space is a group show curated by Johnson + Thwaites. Sharing similarities (and a love letter as part of Kelly Fliedner’s Ships in the Night project) to Léuli Eshraghi’s curated show Ua Numi Le Fau at Gertrude Contemporary, The Fraud Complex includes works from eleven artists that refer to gender, cultural stereotyping, racial identity, artistic conceit and the reliability of images in order to question the division between the real and authentic. Hanging and rotating in the space, Tully Arnot’s poster Waterfall turns the natural splendour of a waterfall into a stuttering loop, reflecting the banal quality of the stock image, while in similar status-seeking anxiety, performance artist Beth Dillon stakes her identity on being The Tallest Artist in Next Wave. As evidence: the certificate of achievement stands proudly in a frame.

Other works including Bindi Cole Chocka’s photographic series Not Really Aboriginal, Técha Noble, Casey Legler and Jordan Graham’s video That Self and Yoshua Okón’s The Indian Project describe similar claims for fraught authenticity. A distracting aspect of The Fraud Complex are the interventions of Johnson + Thwaites surrounding the works such as the addition of living room curtains, brick-printed wallpaper and a bookcase. The attempt to disrupt the traditional white-cube space of the gallery with these objects feels unnecessary. Most of the works don’t hesitate to assert a point and would have benefited from remaining the exhibition’s focus.

Megan Cope’s Aboriginal eligibility test was one such work that confronted viewers. Discover your Aboriginality offered applicants the chance to become a member of the Aboriginal community until 4 June 2016, receive a Coloniser Exemption Certificate or offset White Guilt through payment of an extra $50. If those offers didn’t appeal, we were given the option to join the racist recovery program for $50 – “a self-directed unlearning program that may take a lifetime to achieve”. The first time I looked through the questions in the eligibility test, I was so struck by my lack of knowledge regarding Australian history that I didn’t fill it out. Cope’s work both causes us to question our knowledge of Australian history and gives us an insight into what it is like to have to prove one’s racial authenticity through a judicial process. Playing into hesitancies to give over personal information or just fill out the test, Cope notably placed the pens for the test in a Penguin Classics mug for George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

.jpg)

Continuing on this theme, in 1990, the pioneer hip-hop group Public Enemy’s posse of S1Ws consisted of The Minister of Information, Brother James I; The Supreme Master of Defence, Agent Attitude; The Czar of Education, James Bomb; and The High Chief of Affairs, Brother Mike. Affiliated with the Nation of Islam, and Black Panther movements, the S1W’s left the impression that Public Enemy was as much an organisation as a hip-hop group. And while Chuck D mocked the white middle-class for its Fear of a Black Planet, the S1W’s provided a militant presence to assert the seriousness of the group’s political stance. In the small, chapel-like Black Dot Gallery behind Sydney Road in Brunswick, Hannah Brontë’s hip-hop music video Still I Rise takes up the challenge to imagine a future in which the Prime Minister is an Aboriginal woman in an all-female government. Still I Rise features verses from seven female MCs, who address the relevant issues of concern to a number of government positions including the Deputy Prime Minister, The Minister for Women, The Minister for Education, The Minister of Defence and the Mama of the Mob, “the first tidda handlin’ Indigenous affairs”.

Borrowing the title and its final line from African-American writer Maya Angelou’s poem, Still I Rise, Brontë’s rendition absorbs the resilience of African Americans in continuing to rise above a history of slavery and oppression to make a similar point about the experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people defined by colonialism and cultural genocide. As The Mama of the Mob quips, “You wanna see us in poverty? Not how it’s gonna be”. In a brilliant article for Next Wave’s online publication Wormhole[2] Yugambeh writer Maddee Clark addresses the residual fallacy of colonisation that Aboriginal people belong to the past, and have a diminishing future. Clark sees in Brontë’s work a provocative example of the use of science fiction and futurist genres to portray Indigenous people in positions of power. As the last MC in Still I Rise triumphantly concludes: “I see our Future and it’s wondrously clear/ No longer tied down in a history of fear”.

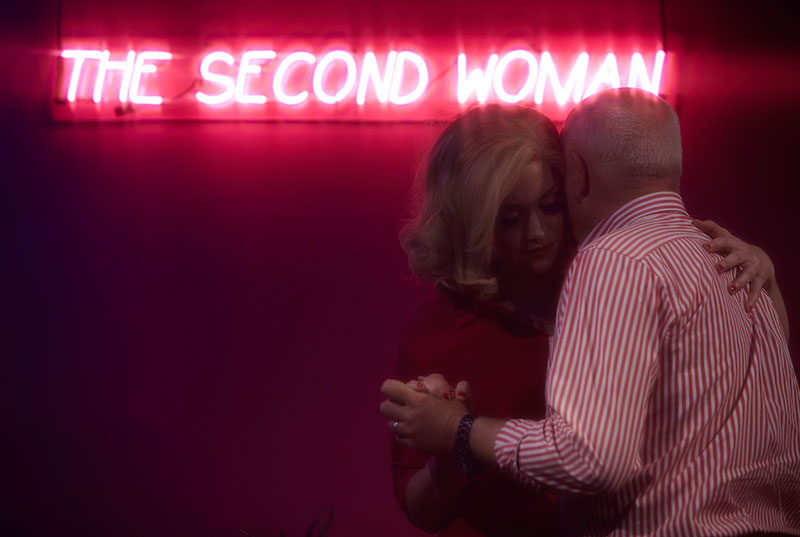

Back in North Melbourne, at Arts House, Lilian Steiner’s contemporary dance work Admissions Into The Everyday Sublime sees repetition and endurance as methods of achieving spiritual repose. Performing exhausting repetitions to white noise, the four dancers appear to be reaching for a tranquil plateau as a resplendence of whirling dervishes re-imagined for the everyday. Using repetition to catch idiosyncrasies and details, for 24 hours at ACMI Nat Randall re-performed a fifteen-minute-long scene inspired by John Cassavete’s cult film Opening Night. Over the stretch of time, one hundred different men played the role of a patronising lover drawing out responses from Randall that included laughter, indifference and animosity. As the short script and actions quickly become familiar, the different personalities of the men and Randall’s reactions to them were captivating to behold. Using duration and repetition, Randall expertly illuminates flickers of authenticity that compels us to keep watching such fraught intimacies.

As with the The Second Woman, the appeal of Next Wave 2016 lies in the variety of encounters. Georgie Meagher has carefully chosen a program to highlight artists and practices that we might not normally see in gallery and exhibition programs, or performances that are too intimate or experimental to be picked up by theatres. Sometimes galleries or performance spaces can feel like they are addressing the expectations of a close-knit group. In the two years leading up to Next Wave 2016, the festival producers travelled to capital cities to meet artists and connect them with local spaces, encouraging dynamic programming . The 2016 festival didn’t hesitate to address issues of colonialism, gender norms and sexual abuse, while balancing aspects of absurdity and humour throughout its program. If the festival moves in a few different directions we should be thankful that it has the capacity to do so and commend its attention to the new.

Footnotes

- ^ Katie West, ‘My art is a personal antidote for the effect of colonisation’, 18 May 2016: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/may/18/my-art-is-a-personal-antidote-for-the-effects-of-colonisation

- ^ Maddee Clark, "Coded Devices", published 6 April 2016 at http://2016.nextwave.org.au/essays/coded-devices/.