“Mary Reilly steals three handkerchiefs. It was a gambit to be transported to join her husband in Australia, exiled for life for stealing food."

A bolt of cloth unravels, spilling down the wide grey staircase. “She had waited five years until their child was of strong enough constitution to survive the four month journey on a convict ship.” A measure of fabric, perfectly square, a small nick with scissors, a resounding tear; followed by another white handkerchief that flutters onto stark concrete. “Her husband was pardoned; Mary was deported, albeit without their child.” Rip, flutter. “Their letters crossed. They never saw each other again.”

Scissors tucked neatly into her skirt Michelle Browne descends the brutal concrete and steel stairs. At each step she relates the fate of an Irish family in the 1820s as the fabric of their lives is wrenched apart. Brave threads cling, fragile connectors to crumpled scattered squares. Browne’s bureaucratic scissors excise them – the last spidery strands are cut, torn away, surrendered to solitary.

Looking down at my own freckled and square Irish potato-picker hands, the legacy of colonisation, famine, displacement and injustice resonates at a cellular level. In the often-repeated cycle, when Irish convicts, settlers and political prisoners reached these fatal shores to the ongoing genocide of Aboriginal peoples, they stepped up a rung on the ladder of oppression. Many struggled, disconnected from their families and homes, while other émigrés enjoyed the high life in the antipodes.

Surveyor Patrick Coleman spread his Irish genes and surname across state and racial borders, including fathering a son with Yhonnie Scarce’s great, great grandmother Dinah Coleman. There she is in a blunt sepia archival photograph hung at eye level above an intimate alter. Dinah’s penetrating gaze watches over an offering of Bush Plums – translucent breath infused glass sand-blasted to whitish opacity. Highly ambiguous, the plums are hard and cold, yet their womb-like curves evoke life and sustenance. Unveiling the romanticism in which she once held her Irish heritage, there is vulnerability as Scarce contemplates other scenarios of power relations between white settlers and Indigenous women in that era.

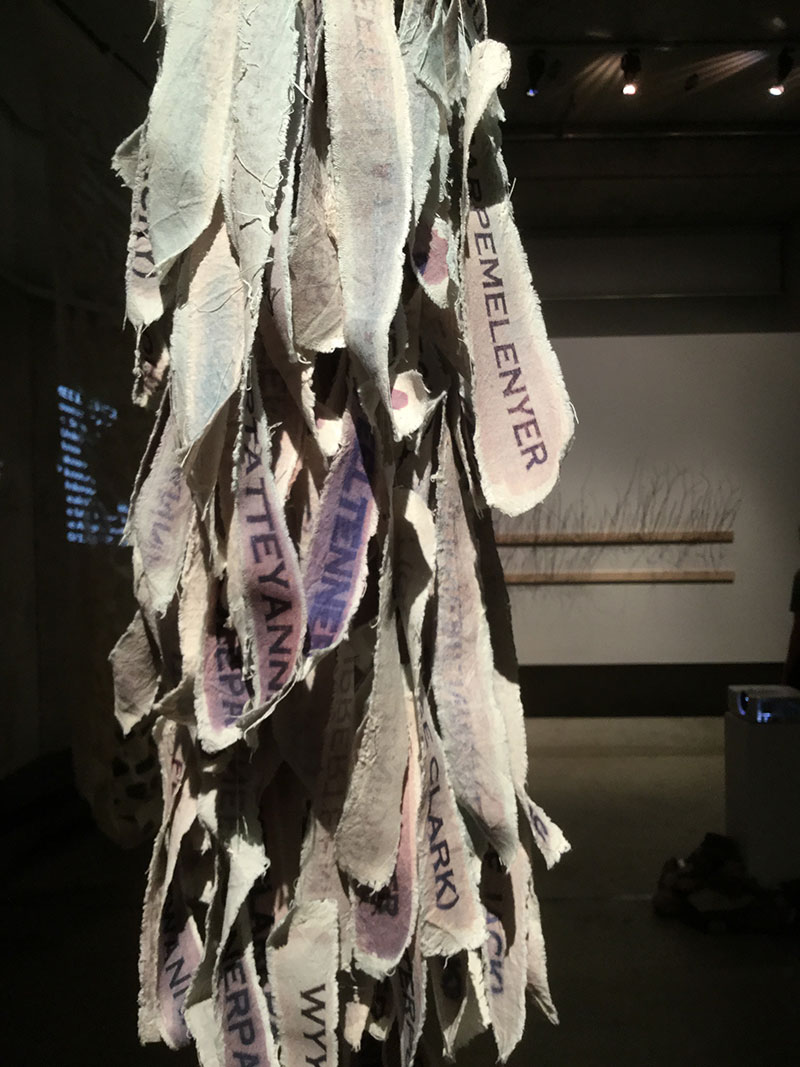

In textures of stone, calico, light, text, twigs and twine, Julie Gough probes that embedded power of the name. Dismal records on Irish arrivals in Van Diemen’s Land shine ghost like through a calico sail emblazoned with rubbings from Irish tombstones. Whether these imports failed or flourished, headstones bear witness to their presence, while Gough’s Aboriginal family's experiences is one of absence. At the same time that the Irish were being imported, the Indigenous peoples of Van Diemen’s Land were exiled to Wybalenna on Flinders Island in the 1830s and 1840s in a “Conciliatory Mission” whose result was rampant disease and mass death.

Solar-printed onto calico, the recorded names of those sent to Wybalenna are individually excised and hung by twine. Hard on a lazy 21st-century tongue, unused to language, they include east coast leader Mannalargenna, Gough’s matriarchal ancestor Woretemoeteyenner and Truganini, the well-known Palawa woman, adventurer, outlaw and ambassador who came to symbolise that genocide. What remains is a soft lattice, a gaping puzzle, a family tree whose every branch has been lopped. I struggle to read the fragmented Aboriginal records of torn lineage, with their leaves clumped, hanging upside down to wither and die. But like drying herbs their potency increases in over time. Viewers are invited to add a rock to the Cairn commemorating named and unnamed ancestors who lie in unmarked graves.

In the gallery space, barely breathing, burying herself beneath glass scattered with spent staples and atonements – small marks made by dot painting with a honeyed stick – is the work of Irish artist Sandra Johnston, who spent several weeks at Warlukurlangu Artists Art Centre, Yuendumu, to prepare for this performance. There, she immersed herself in the community as an observer – an invisible helper mixing paint, pulling staples from canvasses, bringing water and food. Along with the detritus of a desert art centre, she collected the carcasses of community life – deflated basketballs, ash and coals, torn rapper caps.

Her silence amplifies the tension. The shock of post-colonisation is palpable. Waiting for glass to shatter and blood to flow: the honey drips are palpable. Thkump. Thkump. I flinch, clenching my teeth. From my viewpoint, it appears that Johnston had stapled into her own flesh - I want to leave to avoid emotional triggers. But then I see a concave basketball stapled to the front of her red shirt like a womb or a tumor, later to be ripped away. Ash, is then sifted like poisoned flour, icing the scattered objects, strewn staples, sticky tracings. Where does recurrence end … when an audience claps and walks away?

Around one million Irish emigrated during the great Famine, while another million died – a genocide enacted by the British, starving the Irish Catholics out of their homeland. Sue Kneebone’s research in Ireland revealed a cast of ancestors – poor, rich, rebel. Her trademark archival material, as artefacts of colonial settler culture, are darkly humored sculptural interrogations and images projected onto a lowly hung silver-serving tray to narrate the family chronicle. Diseased potatoes, painted a rather shocking copper, with eyes shooting nowhere, scatter on and under a lonely single bed, attesting to the randomness of fate.

The Australian-bound brother became that staple of the justice system, the bent copper – a struggling Police Officer on the take in the gangland Rocks; while the new American, with the luck of the Irish, hit it rich after many years of poverty with an Arizona copper mine. Her chandelier of fallow agricultural tools are strung by chains around an empty chair – it could be one of my great-grandparents’ kitchen chairs. Not empty, really, the chair holds a copper seamed rock and a bible – a powerful allegory of absence, of repression, of journey, of faith.

Swaying gently next to the chair/chandelier, Dominic Thorpe is almost unobserved. But when he drags a colonial dresser across the gallery, climbs upon it and writes on the wall with both hands, the audience notices. Not so much falling silent, but generating a wave of hushed discussion around the room. “What is he writing? He’s dug a hole through the wooden dresser with a teaspoon! I saw Spiderman comics in the bottom drawer ...” Strangers speak to one another to piece the performance together.

Standing in Christ-like surrender, Thorpe simultaneously and repeatedly inscribes in Gaelic and Kaurna (the language of the Adelaide Plains):

remember … forget

remembering … forgetting

how do we remember … how do we forget

Engaging with subject matter of truth and social justice, such as the abuse of children by members of the catholic clergy in Ireland, Thorpe feels a responsibility to consider how the audience may be affected by engaging with another person’s story. He does not aim to upset but to recall with empathy and compassion.

.jpg)

Curated by Mary Knights (who migrated to Australia as a baby with her Irish mother and English father) and Irish artist Michelle Browne, with the assistance of Ursula Halpin, Border Crossings reminds us that we can never be complacent. Successive destruction of cultures through diminished food and resources, dismembered family and repressed language, are tragedies repeated throughout global history. Considering Australia, Ireland, Cambodia, Germany or Syria is to name only a few atrocities committed by one culture upon another.

The day after the official opening, the performers regrouped in the Gallery for an ephemeral four-hour performance with a lucky audience alerted by viral emails and text. Johnston disrupts and reinterprets Kneebone’s chair – bible, rock and ash white footsteps scarring the black floor. Pushed up against the gallery wall behind Kneebone’s 1848 banner, Thorpe sings Gaelic songs of rebellion and republicanism. Browne lays down her torn handkerchiefs to hem and embroider. Besides Gough’s Sail of Irish records they look like children’s graves.

All of the artists will reassemble at the Galway Arts Centre in Ireland in July to re-imagine and reconstruct the exhibition in response to that site. Knowledge making here is interactive, artists work alongside each other and with students. It comes in many forms and relationships – from the hand, the mind, the heart, the individual and their embedded community. When galleries can be experimental and experiential research environments, as SASA Gallery has been for a decade under Knight's Directorship, artmaking becomes a powerful critical tool and a social force.

These fearless artists reveal their familial histories across the artificial borders of sculpture, installation and performance. Poetically echoing and augmenting each other’s investigations into the trauma of the colonised and the coloniser these works evoke the brutality of genocide, the legacy of injustice and unexpected humour amongst oppression. It takes courage and luck to survive, to move on. It also takes courage to retell the tales, to remember the past, to never forget, to hope that history does not repeat.