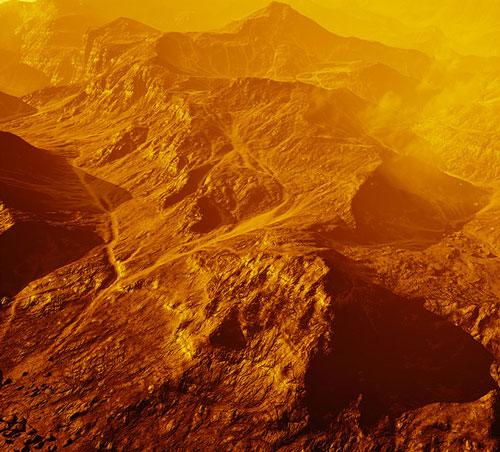

Okwui Enwezor, artistic director of the 56th Venice Biennale, is the Barack Obama of the artworld. Bringing to the act of curating and positioning this "Parliament of Forms" a truly global focus on art and artists, Enwezor privileges an exceptionally broad representation of voices from countries in far-flung or under-recognised regions of the world. Big ideas are expected of biennales, but this one has a particularly compelling urgency and mandate, vested in “The State of Things” to forefront the rout of global capital, impending environmental catastrophe, challenged conditions and histories of labour and civil rights movements.

Summoning up the Zeitgeist, and historical workings of the Venice Biennale itself, Enwezor champions Walter Benjamin's oft-quoted description of Paul Klee’s dark angel of history, propelled backwards to the future while looking upon the ruins of the past. This symbol of the palpable crush and mayhem of being witness to history at a time of conflict, neglect and upheaval is an apt creative metaphor as is the double meaning invested in the word “Futures”, in association with markets.

Amidst the changing world order of nation states, La Biennale is a behemoth, with its curated program and national pavilions representation once contained within defined venues and locales in the city, but now so far expanded into every nook of available real estate that it is impossible to view in its entirety. So, too, the greater ambitions of a program of events, writing, readings, performance, new curriculums unfolding over time through platforms like e-flux, overrides the significance of the opening week to more fully embrace the durational impetus of the longer-standing exhibition and ideas prospectus. It would be easy to lose anchor here. But, somehow, you do get a sense walking through of a big and highly intelligent conversation through art.

Setting the scene in the Arsenale complex, the opening halls are an encounter with crossed words and swords in an installation juxtaposing florettes of knives by Adel Abdessemed and a neon war of words by Bruce Nauman. Walking through, into the adjoining chamber, Katharina Grosse’s Untitled Trumpet, referring to the clarion call of Kandinsky’s spiritual riders of the apocalypse (also a military metaphor), presents an explosion of colour and rubble lifting up the walls and floors of the building.

The relentless dusty traffic of humanity, which includes the crowds of the opening week while intimating the hoards that have descended on Europe with less glorified aims, is represented by Ibrahim’s Mahama’s sack-cloth and rope-lined main thoroughfare Out of Bounds; in effect, turning the entire complex into a gated refugee zone. The Arsenale exhibition, now filling the almost derelict entire outer precinct of buildings right up to the harbour and backlots, features many “new” and not-so-new countries or groups as national pavilions strategically given space in this main exhibition venue. This includes the small Pacific island of Tuvalu as a semi-submerged space under water, negotiated by walking on planks, as a comment on rising sea levels; and edgy smaller nations, like the Latvians, represented by kit homes made out of detritus and outfitted with screen media as the ultimate shed life for survival.

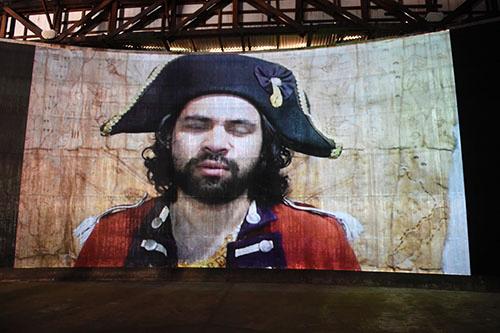

Video art, with its capacity for high impact, in the curated sections, includes the fantastic Fara Fara by Carsten Höller and Mans Mansson, a face-to-face competition and dance-off for audiences of two rival Congolese rumba groups, and the environmentally resonant multi-screen spectacle of John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea made with the BBC natural history unit. In the Arsenale pavilions section, there are video recordings of the extraordinary human tragedy borne out in the hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the South African pavilion and, on a very different register, the equally compelling alternative history of art as a form thing in Sean Lynch’s Adventure Capital for the Irish pavilion.

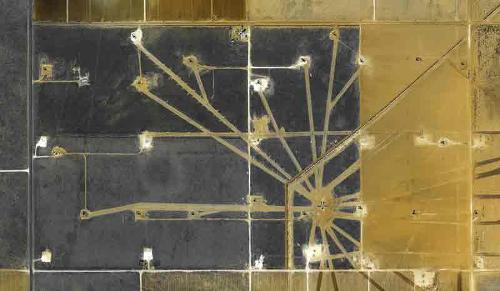

The world of labour and capital is a persistent theme, centred on the provocation of a program of readings from Marx’s Das Kapital and conceptual works that forefront current and past histories of labour and protest, including Jeremy Deller’s collection of 19th-century worker ballads and model of an arm bearing an Amazon Tracking Device, apparently intended to monitor workers’ productivity. In this context, the scale and spectacle of Andreas Gursky’s large-format photographs of the stock markets, a Vietnamese basket-making factory floor and May Day IV are resonant juxtapositions, as are the provocative investigations into exchange value by Marco Fusinato and Newell Harry. Newell Harry’s table full of gifted, traded anonymous artefacts from Vanuata and accompanying text works is a standout here.

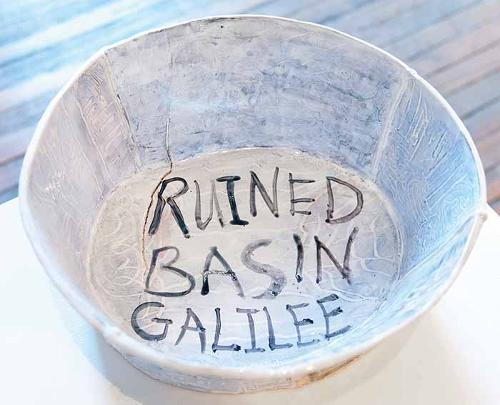

Fiona Hall’s work in the Australian pavilion, Wrong Way Time, is also central to the argument. The new pavilion all painted out in black to disguise its best feature (the view of the canal) has been highjacked by her hoarde of art and artefacts like a reversioning of the South Pacific cargo cult of the 1940s. Her graffitied clocks, infested ornaments, crafted, obsessively annotated and arranged objects as cash crops, all arranged in cabinets of torched charcoal veneer, collectively present one great monument to the Doomsday Clock ticking away.