Lost and Profound represents the fifteenth edition of Gertrude Contemporary's annual Octopus exhibition, for which it invites leading curators to develop their own project. For this iteration, Sydney-based artist and senior curator of Artbank, Daniel Mudie Cunningham took on the challenge, commissioning works across Gertrude Contemporary’s three galleries. Donning rose-tinted glasses, Cunningham’s nostalgic exhibition attempted to articulate the ways in which art practice can thoughtfully reinvigorate obsolete technologies and found objects, creating new ways in which to interrogate memory.

This curatorial framework had mixed success. A number of the artists worked with both retro and found materials, from old photographs to grainy 1950s film footage: for two different projects by Tara Marynowsky and Sam Phillips, vintage vinyl albums were the material of choice. While Marynowsky embellished portraits of crooners that graced LP covers of the 1950s, turning them into fantastical creatures, singer-songwriter Phillips used such album covers as the basis of collages, which were then used to promote her own musical releases. In both works, the artists’ interventions worked solely with the aesthetic qualities of the now much-coveted vinyl record, inadvertently reinforcing the object’s antique quality rather than questioning how nostalgia can manifest in these fetishised objects.

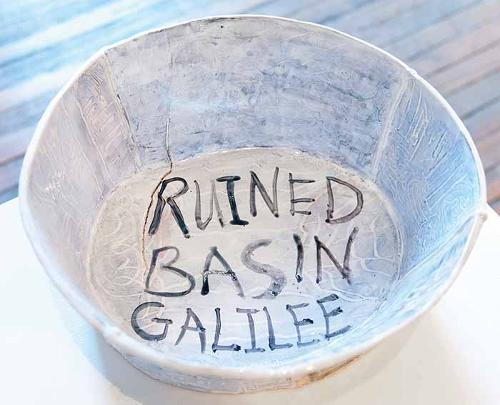

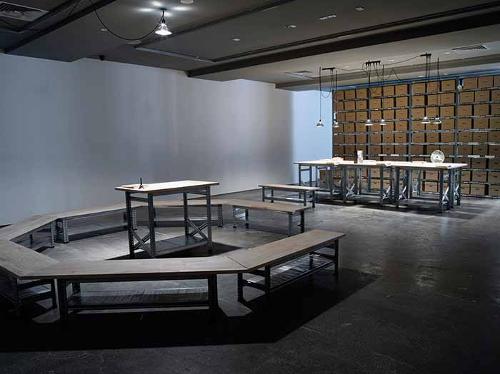

Other works in the exhibition were more successful in creating unexpected narratives from personal archives and collections. Patrick Pound’s The Museum of Falling amassed an array of objects, under the theme of "falling“. Elvis Richardson and James Hayes’ Episode 1: Dear Daddy used an anonymous 1950s photo album - found by Richardson in a flea market – to construct a photographic and sonic portrait of the photo album’s owner “Tony“. Through close scrutiny of the album’s photographs and hand-written notes, Richardson presented Tony’s constructed life: a migrant who had his fair share of romances, with a daughter living in Panama. Richardson opens up a personal tale, one that attempts to deliver not a grand narrative, but rather imagined fragments. By contrast, Giselle Stanborough’s That Really Hurts and It’s Still Hurting accounted for her childhood photographs, which she lost when her father remarried. Stanborough combined images of the artist alone in a darkened room with YouTube screen shots from the home videos of other children called Giselle. The resulting work carried the unmistakable tone of the teen video cam confessional.

Also working in a confessional style, Peter Maloney’s text and collaged paintings weaved together images of homoerotic male nudes, images of violence alongside phrases drawn from the vocabulary of the self-pitying artist. These one-liners, such as “Why am I not in this show?“ overshadowed the more subtle interplay between image and abstract form that occurred in the paintings. Tina Havelock Steven’s Up There presented vintage aerial video footage taken by the artist’s father from the cockpit of his Harvard fighter plane. Steven paired this footage with a digital video documenting the artist herself carrying out durational drumming on the body of a decommissioned plane. While the link between the two videos beyond the use of the aircraft was unclear, Steven’s drumming followed in the recent lineage of contemporary musical durational pieces by pop stars such as The National and Jay-Z.

Lost and Profound endeavored to unpack our relation to archives, to the photos and objects that remain, but ultimately it left a nagging concern – that nostalgia can also be a regressive force. This exhibition could have done with more dusting off.