The Biotech species

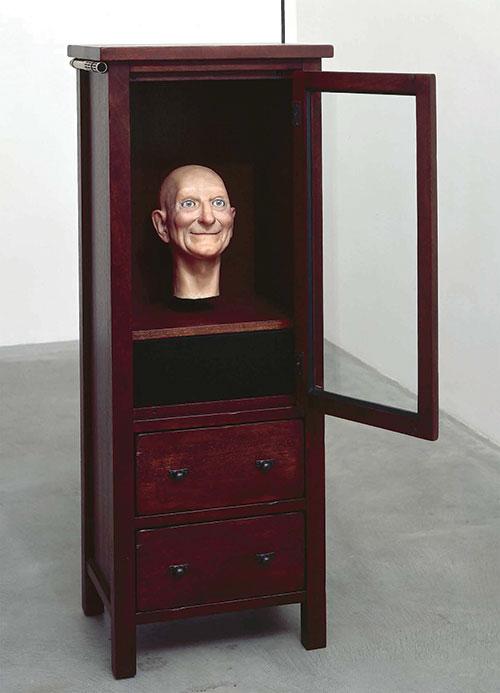

The lesson we have learned from phenomenology is that society and technology co-constitute each other. Current and past events in the development of biotechnology point to the great changes we are going through as society and individuals. The ability to code life into symbols, and being able to interpret these symbols has changed the very notion of what we understand as life. (To complicate matters even further British physicist Stephen Hawking argued that computer viruses should be considered life forms since they submit to all the standard definitions of life). And, indeed, biotechnology and in particular the work with DNA allows us to alter hereditary characteristics. This is advanced even further with bioinformatics and nanotechnology where we can rebuild on an atomic level, and thus shape biological life forms. We have also unravelled the codes of life by mapping thousands of genes comprising the human genome, and have become able to genetically engineer embryos and alter the human species in general. Some hope that at the end of this process we will be able to thoroughly re-engineer life and dispose of death.