.jpg)

John Corbett is the most comprehensively represented artist in the permanent collection of Ararat Regional Art Gallery, which has specialised in the area of fibre art since 1973. Making Time: The Art of John Corbett, 1974–2013 marks the first major survey of an artist whose work has been infrequently exhibited in the past decade.

The scarcity of examples from Corbett’s early career proved challenging for curator Anthony Camm, as the artist often cannibalised his own work, dismantling and reusing materials to make new pieces, or made works of such fragility and impermanence that they have not survived. Corbett has always privileged the process and the exhibition outcome over considerations of commercial appeal or preservation. A small number of objects retained in public collections, and installation photography from the exhibitions themselves, are all that remains of many of these works from the mid-1970s and early 1980s. The eighteen works selected by Camm are both ambitious in scale and expressive of an inherent theatricality; vividly coloured quilts and wall-mounted panels, free-standing and wall-supported sculptures, hanging pieces, and rolled-up remembrances.

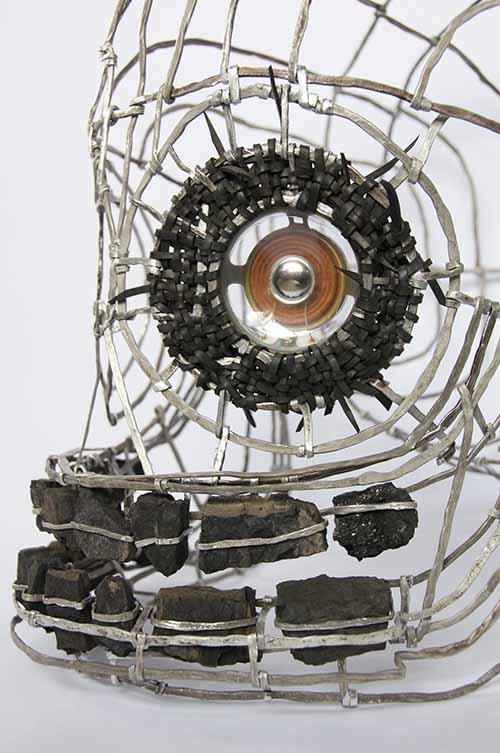

The exhibition traced Corbett’s burgeoning interest in off-loom weaving in the 1970s, a period when he was initially influenced by two Polish artists, Tadek Beutlich and Magdalena Abakanowicz. Turkoman (1975), a pivotal work acquired by ARAG in 1976, was exhibited for the first time as the artist originally intended, and with its proper title reinstated, having been incorrectly catalogued. A woven length of black and white striped cloth with trailing fringes, the work is suspended from the ceiling at a central point and secured by six rocks (sourced by Camm) to form a cone-shaped tepee-like structure. Another work from this period, Hammock (1974), of hand-spun and dyed bright orange wool shows Corbett’s experimentation with the three-dimensional and sculptural possibilities of textiles.

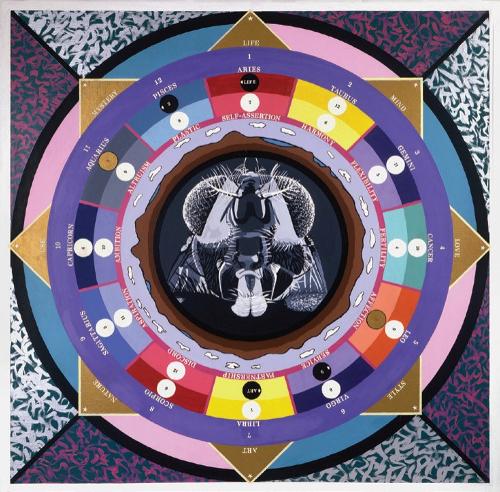

Corbett’s ongoing engagement with international fibre art practices is evident from the text-based assemblages and sculptures he produced from the 1980s onwards. A study tour of America and Mexico in 1987 transformed Corbett’s output. He was particularly drawn to folk traditions, symbols and objects with a ritualistic purpose, such as milagros, votives offerings left in Catholic churches. This influence is discernible in the sole work on paper Milagros Fragment (c. 1989) and the reverse appliqué works Tierra del Ensueno/Toro (1989), and the imposing Journey to Death/El Camino por la Muerte (1989) a three-dimensional wall hanging of multiple layers centred on a cross motif to which over 155 hand-cut aluminium shapes are attached. Another Latin American reference comes via Corbett’s interest in the textile art of the indigenous Kuna people of the San Blas Islands off the coast of Panama. Their symbolically rich molas, featuring riotously coloured and boldly graphic iconography, inspired works such as Portrait (1990).

One of the first Australian artists to confront the emerging AIDS crisis, and to advocate for the wider issue of gay rights, Corbett produced uncompromising works which memorialised the dead, and directly addressed issues of gay male identity. He represented Australia at the 9th International Triennale of Tapestry in Lodz, Poland (1998) with The Loss (1997), one of his meditative “scroll” works to mark the gay community’s grief and mourning. This 2.4 metre work was partially unfurled and secured along the wall, while another scroll piece, The Most Beautiful Part of a Man’s Body (1995) was installed on the floor nearby. Prick and Masculine (both 2000), are more overtly homoerotic, perhaps acknowledging the wider public acceptance of Queer cultural expression.

Rather than any particular desire to align himself with a craft aesthetic, or position his work within the fibre art genre, Corbett has been more interested in the potential for non-conventional materials and techniques to express marginal perspectives and socio-political themes. His scant interest in cultivating the mainstream art world over the course of his career has meant his contribution has often been overlooked. Making Time offered the opportunity for a re-appraisal of Corbett’s unconventional and highly personal artistic narrative.