.jpg)

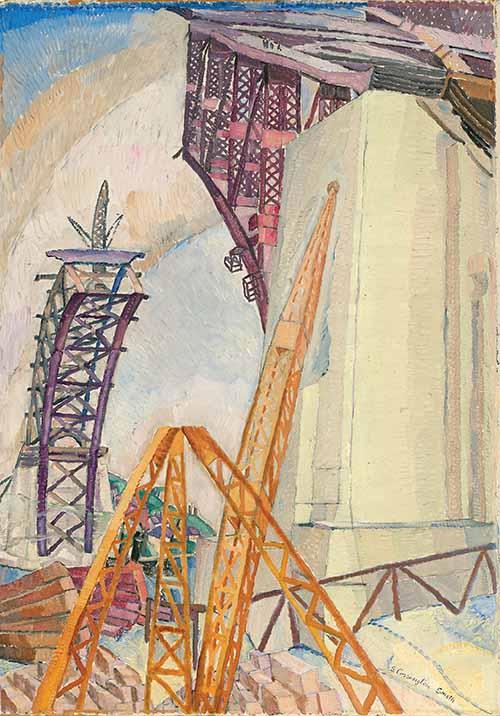

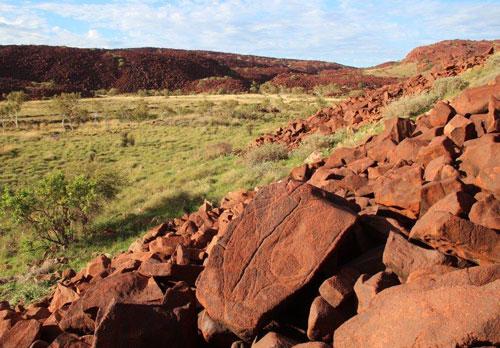

Olga Cironis' exhibition Into the Woods Alone examines a particular species of homesickness. This is not the nostalgic longing for a distant home (nostos: return home; algia: longing), but rather a contemplation of the loss, alienation and amnesia that characterise the aftermath of histories of conflict and migration. This body of work developed through a journey that Cironis made to the Greek mountain villages where her parents were born and her own birthtown in the Czech Republic, exhuming traces of the post-WWII Greek Civil War, the internecine division of the populace and the ensuing exodus into central and eastern Europe. For Cironis, this local history is also writ large in global contexts: in the Cold War, Europe’s economic rise and fall, and white Australia’s anxiety about foreigners penetrating its borders.

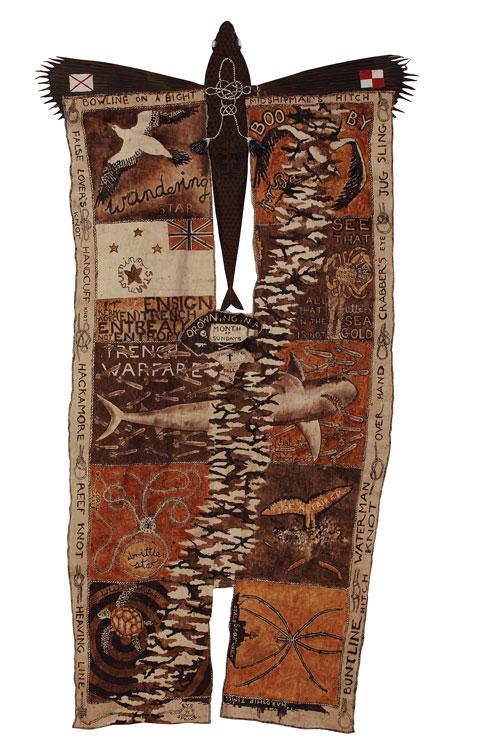

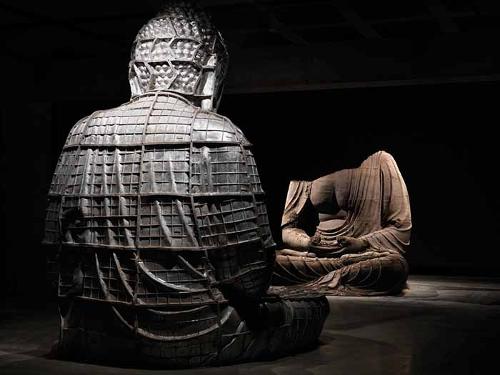

Into the Woods Alone uses devices of framing, concealment and preservation to consider ways in which these histories inhere in places and objects. Cironis’ repeated themes of marginality and invisibility suggest the measurement and archiving of lost time, through motifs such as the steady growth of human hair, places marked by the trace of absent people, and objects wrapped in layers to protect them from the degrading forces of air and light. In Bound by Fate and the title series Into the Woods Alone, Cironis makes use of frames in order to subvert their customary invisibility, emphasising the coded ideals of taste and tradition contained in a scrolling nineteenth-century style gilt frame, or by scratching a rough “X” into the glass shielding a photograph of an autumnal park at twilight.

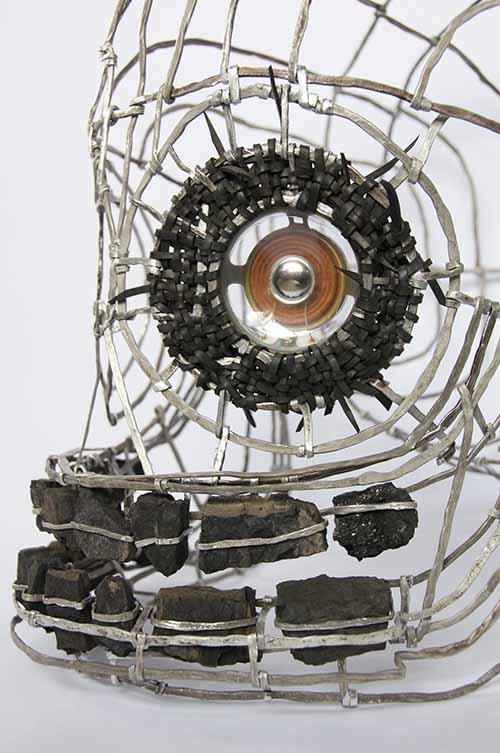

The woven hair in Bound by Fate 1–9 recalls nineteenth-century mourning art, but these slightly abject objects in their kitsch found frames offer no clue as to the identity of the donors, emphasising their anonymity and anachronistic placement. As in a related work, What’s Mine is Yours, in which a glass sphere stuffed with brunette hair is displayed on a wooden stand, the viewer is presented with the material evidence of human life through discarded bodily matter, but these isolated remnants tell us little about the circumstances in which the hair was harvested in the first place. The glass sphere, like many domestic objects and techniques in Cironis’ oeuvre, alludes to women’s practices steeped in long traditions and folklore; this piece evokes practices of scrying or divination in which a lost loved one might be located through the traces they’ve left behind. The anonymity of the hair also erodes the political, religious and philosophical views of the donors, differences that can divide communities; in the context of Cironis’ exhibition the hair is deliberately mute.

Such voicelessness is rendered visible in Alexandra: the artist stands stoically before a tapestry, wearing a headscarf and fur coat, and gazing directly at the camera, her lips stitched shut. This gesture of censorship, reminiscent of asylum seekers’ protests in Australian detention centres, is reflected in her textual declamations, salvaged from overheard conversations – “Can’t we speak of more pleasant things?” and “I ask for nothing” – as well as the stitching of domestic objects into fabric. Whitewash features a blanket dating from the Greek Civil war, still in its original bound state; Cironis will not unfurl it and set loose its secrets.

All of the works in Into the Woods Alone make such occlusions and elisions their central motif, and it is clear that for Cironis the historical narrative, both in its official mode and in the oral testimonies of first-hand witnesses and their descendants, is incapable of providing a comprehensive vision of the past. For Cironis, it is the hidden and indirect ways in which people live out their history that may be most revealing of the import of past events. The artist revisits the sites of her family’s past with a forensic eye, collecting evidence through which to reconstruct her own position in the world, which she describes as “misplaced.”

In some ways this quest puts me in mind of Freud’s 1936 essay “A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis,” in which the ageing analyst recalls his first trip to Athens, where he experienced not elation at finally visiting this yearned-for destination, but rather estrangement. He describes a fleeting incredulity that the Acropolis truly existed, an intense experience of derealisation that led him to doubt the evidence before him. In Into the Woods Alone, Cironis seems to be negotiating a comparable sense of derealisation in the wake of historical experience, encountering the fundamental strangeness of the past whilst mining it for evidence.