The Tiwi people of Bathurst and Melville Island have established a unique place in the history of Australian art due to their distinct culture and contribution to modern-day Indigenous arts practice. Nevertheless, in recent decades, Tiwi artists and crafts persons have been marginalised in comparison to popular focus on Central Australian and Arnhem Land art. Jennifer Isaac’s recently released Tiwi: Art/History/Culture will undoubtedly inspire a major re-evaluation of Bathurst and Melville Island art and become a definitive text for collectors, curators, historians and general readers. More importantly, the lavishly illustrated volume provides a major resource for contemporary Tiwi artists seeking to understand their own aesthetic heritage at a time when ceremonial practices are ceasing and almost all locally-produced art is destined for mainland or overseas destinations.

Isaacs presents her subject with the nuanced understanding of an experienced Indigenous arts curator and historian who has had forty years association with the Tiwi Islands. The only previous publications, both now out of print, exploring the breadth of the subject are the anthropologist’s Charles Mountford’s meticulous compilation Tiwi art and ceremony, 1956, and Cathy Barnes’ Kiripapurajuwi: Good craftsmen and Tiwi art, 1999. Tiwi: Art/History/Culture defies the common fallacy that there exists an inevitable contradiction between scholarship and so-called ‘coffee table’ publications. Isaacs’ text is readable, and entertaining as well as being meticulously researched and annotated. The Miegunyah Press designer, Marian Kyte, has produced a publication tour-de-force in the page by page juxtaposition of text and images. This is a book that can be read methodically chapter by chapter, commencing with The Islands and its People to the concluding postscript Looking After Tiwi Culture, or opened at random and browsed with pleasure.

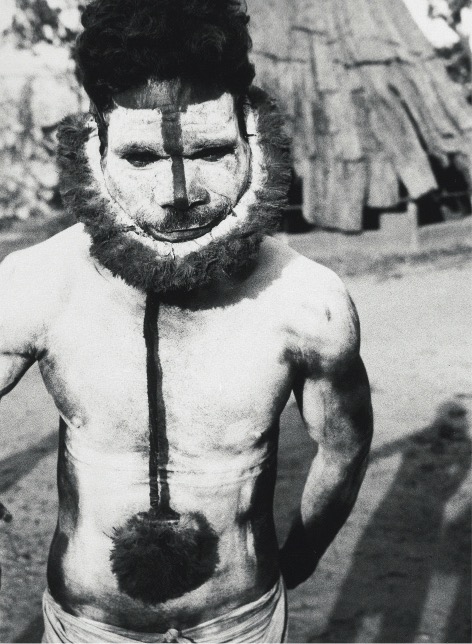

Tiwi: Art/History/Culture is full of surprises. Isaacs’ diligent research has uncovered much previously unpublished archival material such as Herman Klaatsch’s 1906 hand coloured photograph titled Burial posts at Lusmore Head. The author explores the extensive collections made by Walter Baldwin Spencer in 1912-1913 and Charles Mountford in 1954. She astutely observes the vibrancy of the 1954 art documented by Mountford may reflect the artists “determined display of Tiwi-ness to non-Tiwi”. Nevertheless, it is the bold designs and intense colours of the natural ochres available on the Tiwi Islands, used during the 1960s-1970s by artists like Mani Luki and Micky Geranium, which astonish. Ironically, the sedentary nature of life at Milikapiti under government welfare management encouraged the production of spectacular ceremonial sculptures despite Tiwi residents being forbidden to create art during the five-day working week. At this time artists willingly pre-sold burial poles to visiting collectors, even before the actual ceremony. Isaacs faithfully records the subsequent development of the art centres of Tiwi Designs and Tiwi Pima at Wurrumiyanga (formerly Nguiu), Munupi Arts at Pirlangimpi and Crafts and Jilamara Arts and Crafts at Milikapiti. These enterprises became influential role models for many similar organisations established in remote communities during the 1980s-1990s. Among the surprises are the charming paintings by lesser-known artists, such as Jane Tipuamantumirri, working at the Ngaruwanajirri enterprise. Also, surprising are the Tiwi Pottery utilitarian ceramics that initially appear so bland in comparison to the islands’ lively screen-printed fabrics. Early examples illustrated in Isaacs’ book have a dignified presence equal to the best Chinese Song Dynasty wares which were their inspiration though the influence of the potters, Englishman Michael Cardew and Australian Ivan McMeekin.

This book has been produced at a timely moment in Tiwi art when few people on the islands, as Isaacs observes: “regard old Tiwi cultural behaviour as the absolute priority for modern life and the young lack an understanding of the past”. The symbiotic relationship between culture and art is sensitively explored by Isaacs and re-affirmed in statements by individuals such as the artist Pedro Wonaeamirri. Tiwi art, with its emphasis on individual expression rather than the reproduction of conventionalised totemic motifs, has proved to be remarkably resilient despite periods in the late 1970s at Wurrumiyanga and again in the late 1980s at Milikapiti when making virtually ceased. It is curious in the light of the clear connection existing between art and culture that subsequent art revivals have not been reflected in ceremonial life. In the early 1990s, during which time art-making began flourishing again at Milikapiti, there was an ongoing decline in pukamani and kulama rituals. Ceremonial body painting was applied in an increasingly perfunctory manner, painted wangatunga baskets ceased to be made, improvised songs no longer accompanied dances and body ornaments were ‘borrowed’ from community museum displays rather than made specifically for the occasion. Today it is the art enterprises that have become responsible for maintaining art practice and nurturing skills, and the choice of media more often reflect monetary incentives rather than older cultural imperatives.

Tiwi: Art/History/Culture enables a contextualised understanding of Bathurst and Melville Island art by Tiwi and non-Tiwi alike as Isaacs’ selection of illustrated art works is both aesthetically informed and ecumenical in taste. Today it is still considered largely taboo to critically judge Indigenous art although this is not the case on the islands themselves. In 1989, while I was living and working as arts adviser at Milikapiti, I witnessed the respected elder, Justin Puruntatameri, declare the postponement of a pukamani mortuary ceremony to around one hundred gathered mourners, because he considered the carved tutini poles below standard. Tiwi art has often displayed an uneven quality. Don Hocking Budjameri Tipakalippa’s figurative paintings from the early 1960s may be ethnographically interesting but they are not invested with the power of other works from the “Paru mob”. The introduction of the chainsaw in the 1980s had a devastating influence on carving and resulted in the mass production of poor quality tourist items generically known as ‘beer birds’. The book’s survey permits a more knowledgeable assessment of famous artists such as Kitty Kantilla, and Timothy Cook whose transformation from social fringe-dweller into community celebrity must be one of the more remarkable stories in contemporary Australian art. It is doubtful whether history will much remember the work of Freda Warlapinni who commenced painting late in life on the wave of the ‘Emily phenomena’. In every remote community, art advisors and dealers were encouraging elders to take up the brush in the hopes of discovering another Kngwarreye. Warlapinni probably had greater insight into her abilities than many who promoted her. She titled one painting Pwaja pukamani which may be loosely translated “the leftover pieces of pukamani designs”.

Sadly, I was mindful reading the book that the names of several remarkable contemporary artists are missing. Their youthful potential was tragically cut short by alcoholism, prison terms and self-harm. The Bathurst Island artist and potter, Jack Puautjimi, laments: “too many problems in town, fighting, suicide”. Tiwi: Art/History/Culture presents the opportunity for Tiwi artists to look back with pride at the past and with creative insight into the challenges of the present because, as some say: “we living in the future now”.