The original South Australia Illustrated was the title of a portfolio of images by the colonial artist George French Angas published in London in 1847. The optimistic spirit of this publication lived on in South Australia Illustrated: Colonial painting in the Land of Promise. The project owed much to the curator, Jane Hylton who, since the beginning of her professional life at the Art Gallery of South Australia in the early 1970s, has pursued an interest in South Australian colonial art. With an extensive exhibition containing iconic, less well-known and rarely or never exhibited works accompanied by a major publication, SA Illustrated looked the total package, perhaps the last word on the subject. In curatorial terms there is of course no such thing.

The depth of scholarship and extensive gallery of images embedded within the publication have opened up further opportunities for survey exhibitions combining artworks from major and regional collections across Australia to create nationally inclusive narratives about the colonial experience. An example in SA Illustrated is the subject of encounters between Indigenous people and colonists. This was one of the standout themes of SA Illustrated, not only because of its relevance to contemporary audiences, but also because the imagery by artists as diverse as S.T. Gill, George French Angas, Charles Hill and Alexander Schramm remains so compelling. S.T. Gill's bustling street scenes in which Aborigines and colonists go about their business and Alexander Schramm’s detailed studies of Aboriginal encampments underscore a complex, and to contemporary eyes, contradictory state of affairs of an almost surreal society barely held together by rituals and rules from the other side of the world.

No less intriguing is the visual record of a settlement becoming a city. To have in one exhibition William Light’s euphoric illustration of Rapid Bay, J. M. Skipper’s earnest sketches of colonists stepping for the first time onto the sand at Holdfast Bay, Martha Berkeley’s watercolour of a North Terrace barely scraped from the bush, S.T. Gill’s 1845 watercolour of Charles Sturt’s expedition clearing the city in 1844 and Eugene von Guérard’s c.1860 oil of a distant view of Adelaide, infused with Claudian gold and featuring the North Arm of the Port River shining like a national guitar, was a special journey in appreciating how the people of this 'Land of Promise’ yearned and strove for a city jewel in its crown.

Around such aspects which also include the significance of portraiture within the art market economy (particularly around the 1850 - 1860s), the impact of a mining driven boom economy, the publication and exhibition of work in Britain to promote investment and migration, artists at the forefront of exploration of coast and hinterland, and the significant achievements of women artists including Martha Berkeley, Alice and Helen Hambidge and Rosa Fiveash, a compelling narrative has been created, which oddly enough, resonates with present day realities.

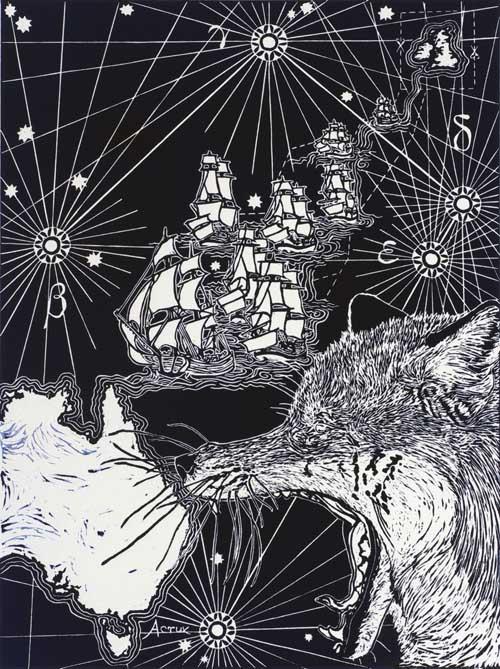

If the topic of South Australian colonial art is to be revisited at a later date emerging trends in art museum interpretation would almost certainly demand the inclusion of colonial photography. SA Illustrated and its majestic, period-style publication designed by Antonietta Itropico, almost reads as a valedictory, a consignment to future generations of South Australians whose grandparents never swore allegiance to Queen Victoria, and who may sometimes wonder why Adelaide does things differently. This point of difference is honed to a fine edge by Hylton when her research looks squarely at the loss of momentum in South Australian art in the later nineteenth century. Early artists, such as George French Angas, came with the intention of working professionally and promoting the colony through their art. That Angas held Australia’s first major one-person exhibition, in Adelaide in 1845, is one example among many cited by Hylton, of this fledgling colony’s cultural self-assurance and capacity to achieve.

The root causes for the later nineteenth century loss of momentum: isolation, a relatively small population base and a sputtering economy have continued to cast shadows over efforts within South Australia to sustain critical mass in the visual arts. But against this SA Illustrated (the publication) highlights examples of vision and cultural nerve, as exemplified by H. P. Gill’s contribution as Honorary Curator of the Art Gallery and Director and Examiner of Technical Art at the School of Design. By taking the reader behind the scenes to get a real sense of the events and personalities associated with the establishment of the School of Design and the National Gallery of South Australia, within the broader narrative of painting in colonial South Australia, Hylton has articulated a characteristic trait of Adelaide’s visual art community to organise, collaborate and be self-reliant.