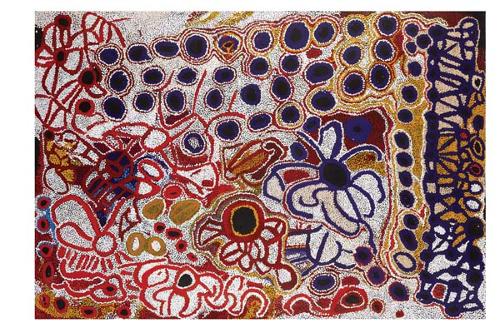

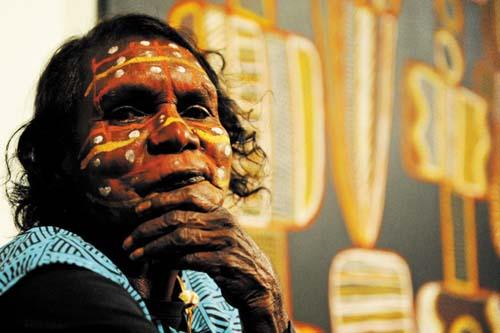

In the last few years of her long life the renowned artist Kumantjayi Napanangka, who was awarded the Order of Australia posthumously in 2011, experienced both the heights and the depths of the Indigenous visual arts sector. She won the National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award in 2008. At the same time she was subjected to extraordinary exploitation as she was photographed as a frail object draped in poorly rendered fakes apparently giving credence to shoddy works done by others in her name. Examples posted on the web by those still exploiting her today can readily be seen.

The treatment of Kumantjayi Napanangka epitomises the problems which have undermined the public's faith in the Indigenous visual arts (IVA) sector. From its earliest beginnings there have been two substantial issues that have cropped up time and again.

The first involves a range of unethical conduct, against artists like Kumantjayi Napanangka. It involves the relationship between artist and dealer, the treatment and payment of artists, through to issues around the representation and the authenticity of artworks.

The second issue involves the professional relationships between the dealers in the sector, be they private commercial galleries or not-for-profit players. Dealers of all varieties and persuasions have become adept at impugning their competitors by claiming they are unethical or incompetent. Sometimes these accusations play out as the 'art centre wars’ in which community based art centres are pitted against a range of mainstream galleries and other commercial competitors.

Disputes about both of these issues can and do bring disrepute to the sector. They cause confusion and chaos in the market, and they are pivotal to the portrayal of this sector being written off as dysfunctional and ‘troubled’ in some sections of the media.

These matters have been playing out over decades. In 2006 the then Liberal Government launched a Senate Inquiry into the Indigenous visual art and craft sector. That there was a Senate Inquiry at all into a sector as small and confined as Indigenous visual arts is telling. It says much about the seriousness of the claims of misconduct and the effect of that misconduct on the endemic poverty and inequality experienced by the artists whose work is the absolute bedrock of the sector.

In many ways the Senate Inquiry report has shaped public policy in this area like no other instrument. Its recommendations have been taken on board, almost as an article of faith, by the current Government and central to them was the establishment of an industry code of conduct. The industry negotiated the form and content of the Code over an extended period and it has been operational now for just over a year.

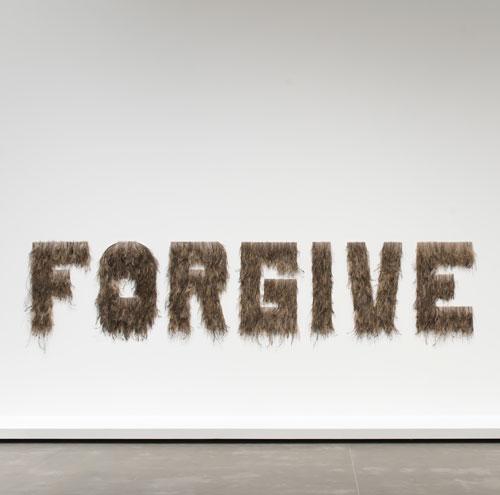

Put simply, the Code is a set of principles based in Australian competition and consumer law. Dealers in this voluntary Code become signatories and commit to operating according to the principles described in the Code. If they fail, a complaint can be made and the disciplinary procedures of the Code imposed. Sanctions against members can include the imposition of a bond, suspension and, ultimately, public naming and shaming. There is ample evidence that in disputes people do treat the code with respect, agree to modify their behaviour and avoid naming and shaming. This is a good result. The outcome is better treatment for artists and increased professionalism by dealers. For the first time there is a mechanism to police industry behaviour and to give indigenous artists a fair go.

In a little over a year since the Code was officially launched on 29 November 2010 we have already signed up more than 200 members across Australia, ranging from artists in Cape York to leading collectors and a significant group of art dealers. We’ve even had strong support from important overseas galleries. Over the past year there have been 15 complaints and disputes dealt with under the Code. One serious matter involving alleged illegal conduct has been referred to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). All other matters have led to negotiated settlements involving improved conditions for artists and more accountable conduct by dealers.

In a short space of time the Code has carved out an important place in the sector. Its members represent a sizable proportion of the industry and no other organisation has been able to bring together such a diverse group of players from across the whole sector. Those involved are proud of the work done so far, and are conscious that there is a big job ahead to safeguard the reputation of a vital industry for Indigenous Australians.

What has surprised me most has not been the resistance from the ‘shonky’ dealers refusing to modify their behaviour but the non-committal attitude demonstrated at the top end of town. I believe these galleries have a real opportunity to take a leadership position on a matter of great importance in Australia. That they have failed to engage with enthusiasm so far has been a real disappointment. I am most surprised by the contradictory position of the Australian Commercial Galleries Association (ACGA), which led the fight for ethical dealing in the IVA sector. In a recent article published in the February issue of The Melbourne Review the ACGA claimed a pivotal role in developing both the Code and the Resale Royalty Scheme. In fact, it does not publicly support either. The ACGA points to its own thinly sketched code of ethics as sufficient. This is frustrating mainly because it misses the point, which is to bring together the entire Indigenous art community to embrace a standard of ethical dealing for Indigenous artists which artists, dealers, collectors and customers can embrace.

The Indigenous Art Code offers a unique solution to the fundamental problems that beset the sector.

It is fundamental strategic reform in a sector which is distinctively Australian and a vital economic lifeline for Indigenous Australians. It is also a sector which is one of the last bastions of unregulated activity and which has been damaged in the minds of many people by lingering suspicions of unethical behaviour and exploitation. In the past four decades industries across Australia have embraced strategic reform designed to give the players and the consumers in those industries greater confidence and greater efficiency. The IVA sector is one of the last to come to this process and in doing so it often exhibits its underlying conservatism and division.

Unless the Indigenous art sector can rally together in support of the Code the long-term damage to the Indigenous art industry and the Indigenous communities which depend on it may be far-reaching, and even the top end of town will not be immune. There is still time for those galleries and organisations who aim to be leaders in the visual arts to show more and better leadership in an area of national and international importance - by proudly showing their support for the Code and the work it is doing to make sure indigenous artists are given a fair go.