The biennial photo feast that is Fotofreo is in its sixth incarnation this year. The core program consists of twenty-two exhibitions spanning fifteen venues. Add to this the Open Program (or fringe) with eighty-eight exhibitions across Perth, including an epic installation of photo-essays by more than sixty Australian and international photographers at the cavernous Midland Railway Workshop, and you have perhaps more than can be absorbed by audiences over the month of the Festival.

Inspired by international photo festivals being embedded throughout compact cities such as Arles in France and Pingyao in China, the first Fotofreos relied entirely on volunteers and enthusiasts. They were focussed on Fremantle, a port city adjacent to Perth, where heritage buildings are dwarfed by giant container ships and the smell of the live cattle trade wafts across the town on the sea breeze. It is a perfect setting for the meeting of local and visiting war correspondents and photo-documentarians, fine art and landscape photographers, photography academics, curators and commentators and enthusiastic photo-lovers and students of photography. Fotofreo was invented by a gang of local photo media practitioners who wished to bring the international dialogue that they experienced overseas to their home town by inviting inspiring others to Fremantle to show, to talk and to party.

Today's Fotofreo has grown to sprawl across the whole city of Perth and perhaps some of the early energy and edge that marked its beginnings has been dissipated. The twin themes of landscape and portraiture, mainstays of the art of photography, are dominant. Portraits of Fremantle, Broome and Port Hedland inhabitants at work, home and play combine these genres in the show No Worries: Martin Parr where this outsider sets out to capture the quirky essence of Australia. His images are big, colourful and engaging but somehow the underbelly is absent, creating an all-too-cheerful portrayal. Bo Wong’s portraits, displayed as banners overhead in the fruit and vegetable section of the Fremantle Markets, have a grace and mystery reminiscent of the work of Bill Viola, with the protagonists focussed on their inner worlds, seemingly oblivious of the camera. The viewer is invited to create the back-story, as they are in Bronek Kozka’s slick images of suburban life; like film stills suggesting dark narratives being played out in front yards and behind closed doors. Traditional documentary is alive in the understated fringe exhibition by Alastair McNaughton, The Shacks, examining the lifestyles and dwellings of some of the community of 178 shacks struggling to hang onto a tiny strip of coast between sea and highway at Cockburn’s Naval Base, just south of Perth. The impoverished but beloved shacks perch on an idyllic beach right next to an area of heavy industrialisation.

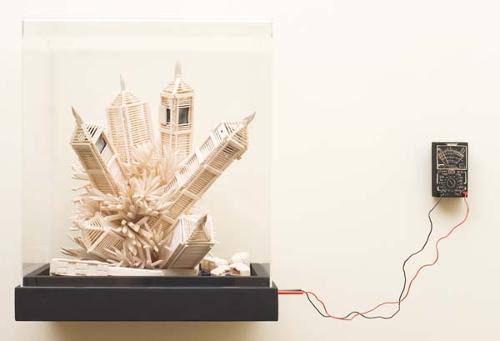

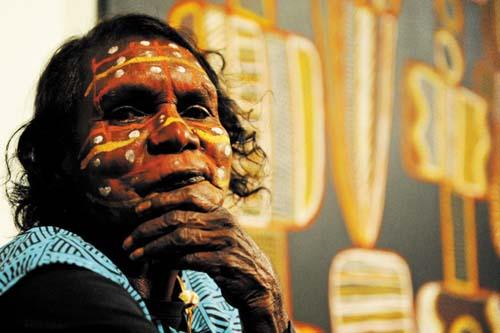

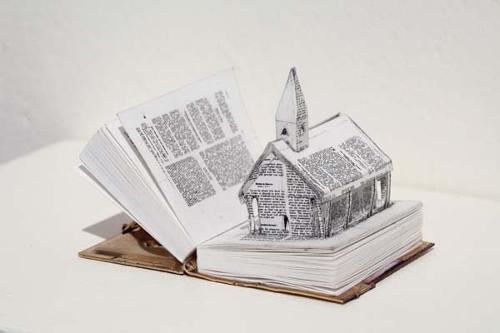

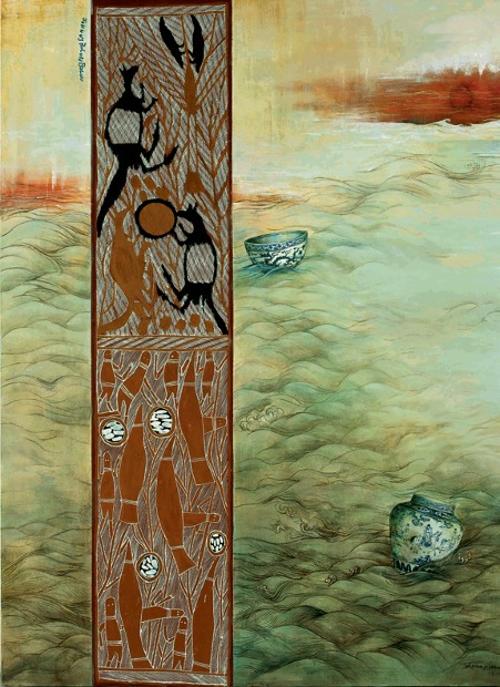

It’s a giant leap from these insights into the real and imagined worlds of Aussie battlers to PICA’s exhibition of cutting edge contemporary Australian and UK photography, Hijacked III. This shows sets out to explore "what it means to look at, create and construct images in the 21 century". Hijacked I was Australia/USA and II was Australia /Germany. For each show, an impressive book has been published locally by Big City Press; this version with 10 writers, 3 curators and 35 photographers. The first Hijacked was shown in a series of less than adequate hallways. It was a raw celebration of humanity in all its strangeness and ugliness. In version 3, where there are people, their faces are nearly always obscured; their gaze averted or hidden. Christian Thompson’s monumental 3 metre image from the series King Billy is a faceless portrayal of his ancestor (a senior tribesman of the Bidjara people) swathed in Aboriginal motif fabrics, crowned and holding a kind of chalice which is the bottom half of a plastic bottle, heavy with signification. It is an imposing and confronting image, seductive and bewildering. Another Indigenous artist, Tony Albert, depicts family members in gaudy Mexican wrestling masks, a new generation of warriors protecting their paradise in north Queensland.

Helen Sears’ quiet montages depict people from behind in landscapes overlaid with hand drawn netting. There are wedding photos with faces whited out or scratched off by Natasha Caruana and water-damaged old family snaps by Seba Kurtis. Alin Huma’s series End of Film, was shot with a camera devoid of viewfinder or focussing mechanism in order to reduce the technical qualities that he felt “shut down the conceptual power” of photography.

This is all thought-provoking but Huma’s photographs, like many in the show, are heavy on concept at the expense of compelling imagery. I preferred the performative approach of Trish Morrissey’s interventions into random families taking recreation at the beach, by inserting herself into the image. But then Hijacked III is not trying to amuse me or make me feel good, but to disrupt the way I think about photography. In this it succeeds beautifully.

Hijacked III will be on at Griffith University Art Gallery, Brisbane 27 April to 16 June and then the Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney 29 June - 19 August.