Although Western Australia produces a great deal of remote and regional Aboriginal art, Perth sees little of it. The capital of the state is an artistic vacuum compared to most places, and more so when it comes to Aboriginal art. To see the Ngaanyatjarra masters, or the recent innovations from the Kimberley or Pilbara, you are better off in Broome, Singapore, Sydney or Melbourne. In the last few years, however, there has been some effort to build bridges from Perth to the far north and remote east, across the desert plains. The state gallery's Indigenous Art Awards are the most prestigious of these efforts, while new commercial galleries have all played a part in bringing quality work to town.

But the city’s TAFE college Gallery Central has now hosted a couple of events that show another side of Aboriginal art. Modelled on the frenzied Desert Mob market in Alice Springs, the Revealed Marketplace opened the eyes of local punters to the sheer quantities of painting moving out of remote country. And as with Desert Mob, the market is paired with a show that foregrounds the freshest of works from the art centre movement. In Perth this show drew on 50 of the less established artists from 18 different art centres, including from the southern half of the state. The promise of new art centres and galleries at Canarvon, Geraldton, Mount Magnet and Wiluna is to make visible an Aboriginal culture that is all too often presumed to have been destroyed by colonial policies. Western Australia’s forced adoptions and re-education camps decimated the state’s southern Aboriginal people, yet families did manage to stay in contact and to reconnect amidst it all. The painting Lost by Andrew Binsair from Wirnda Barna Artists at Mount Magnet contains something of this historical tragedy, as an imagined Aboriginal elder of the pre-colonial times peers forth from a starry sky.

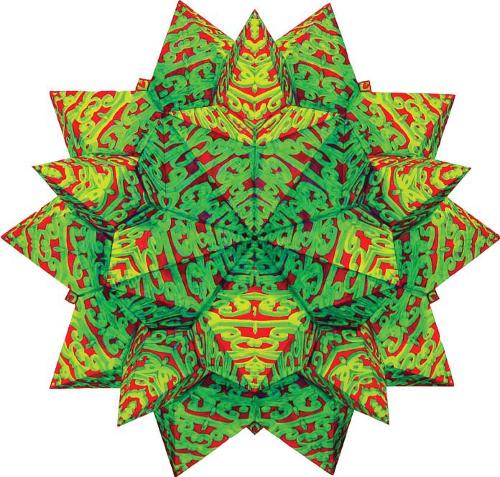

The northern coastal community of Kalumburu has also been dismissed for losing touch with its Aboriginal history, as it remains in the grip of a mission that has somehow survived into the twenty-first century. Here a recent project to revive an art practice in the far north has brought about a flourishing of unusual and distinctive styles that testify to something special in this northern outpost. At first the trippy designs of Mary Teresa Taylor and the underwater scenes of Mary Punchi Clement appear to be a completely secular art. Yet, as with Binsair’s iconic portrait, there is something more there, an insight into the spiritual life.

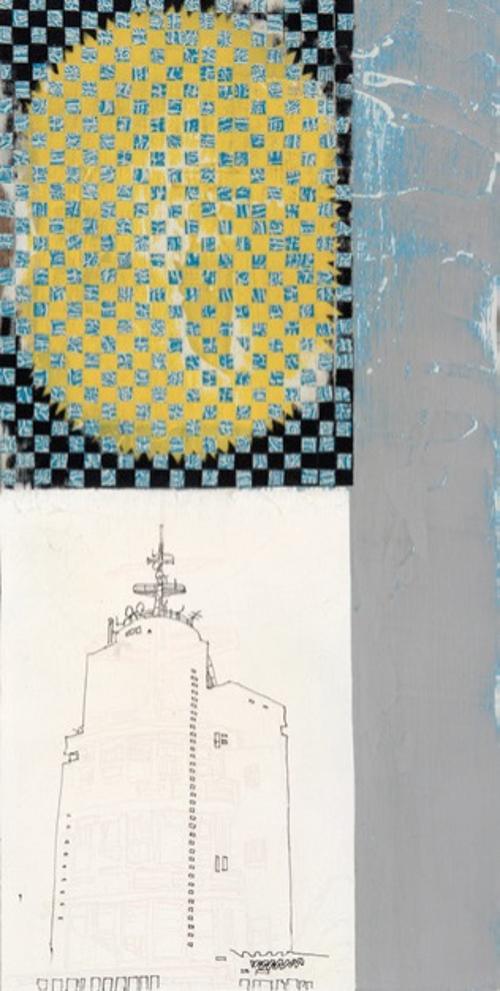

Another dimension of interest in this show lies in its punu (wood carving) and weaving. Barbed spears, camels, hitting sticks, boomerangs, lizards and camp dogs are among the objects on the gallery floor. These objects tend to pull the paintings off the wall, their colours and designs bouncing off the acrylic and ochre. It’s a good strategy for curators who want to liven up yet another painting show from remote Australia to include something else, something that testifies to a more plural material culture. It gives paintings something of a context. The wallwork is not only by painters or art centres, either. Vanessa Russ, originally from the Kimberley but now a Perth resident, exhibits some interesting graphite on paper works that riff on Warmun designs without reproducing them.

Revealed, then, can be understood as a part of a local trend to begin to showcase the variety of Aboriginal art that is being made across the state. Amidst this diversity, classical desert dotting appears to be a fading glimmer of an art movement of the past. Aboriginality lies as much in one media as another, in one part of the country as another. What binds the work is that which holds Aboriginality together, a fidelity to the country itself. This is the power of much of the new work from the south, as well as that of the far north, that it responds to something in the land that both compels and eludes within the art itself. This is the power that is missing from much of Australia’s artworld, that oscillates between high pretension and commercial banality, between careerism and decoration. While this situation exists, shows like Revealed will maintain their relevance, as even the worst of Aboriginal art possesses the aura of its own necessity.