Melbourne’s Docklands is known more for its urban development headaches than its unique environmental and spatial qualities. Massive structures, railway lines and a stadium obstruct the flows of vibrant Melbourne across to the west; high winds and vast concrete offer an unwelcoming first greeting; many locals feel unsupported by infrastructure and services. Creating a testing ground for place activation, RMIT’s OUTR presented Urban Realities, one hundred local and international participants competing in ten teams for a $20,000 jury prize and a $5,000 popular vote.

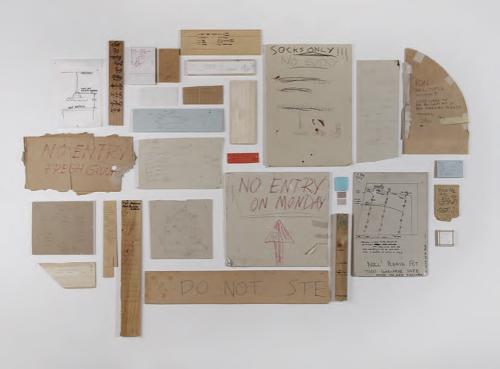

The working constraints were basic, yet ripe for fast experimentation against the pressures of time and constant public engagement both onsite and online. Teams had a $2,000 cash budget plus $500 for The Pantry, a store of donated materials. Participants lived and worked onsite, with Shed 4 as their headquarters; any bought materials needed to be sourced locally; no ground penetrations were allowed. The ten sites were scattered all over Docklands, some kilometres apart, with specific project briefs sensitive to each site: healing, transplanting, filling, stitching and connecting place.

As one of eight local and international jurors, my experience of Urban Realities was multiple. I cycled across the incomplete sites on Friday evening to witness their emergent place-making. The next day, the formality of the jury’s tour involved a presentation from each team. Here, the distinctions between program and performance, design and art were brought strikingly to bear on each work through the teams’ newly developed site vocabularies. Aesthetics were grounded in contextual references; material choices referenced environmental concerns; process was articulated into final function.

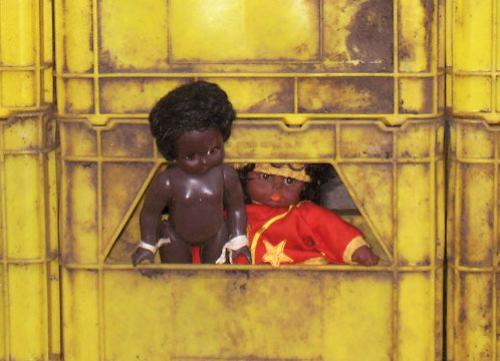

The finished works were diverse: a set of orange kites; a sandpit beach; a bottle-cap game; a reconfigurable gathering place and bike station; a garden of transplanted weeds. The People’s Choice winners, Team 2 or the MAD Collective, created a lightweight structure which opened new sight lines and connections at a pedestrian intersection next to construction hoarding. Tens of thousands of little blue strips were tied to steel mesh, maximising the wind’s power to create sound and movement; each strip had been painstakingly hand-cut, crafting an extended life for disposable plastic overalls, leftovers of a street art exhibition, found in Shed 4.

The winning work was Dirtybuoy by Team 5: Alysia Bennet, Paul Coffey, Stuart Harrison, Jeremy McCloud, Nicole Mechkaroff and Phillip Smith. Briefed to diagnose the site’s unknown illness, the team presented an analysis of the harbour water as the material weight of their structure. Transparent storage tubs interpreted the water’s depth and composition into four layers at 1:1 scale. Opposite them 1,200 bags of water pegged onto metal hoarding created new picture-window views across the harbour, as well as reflecting different lighting conditions: natural light, street lamps, fireworks and the big screen — which the team further exploited by creating an explanatory presentation, adding to their social media strategy.

“We ended up making something that we found quite beautiful: it was about water, it was about light, it was about wind," said Harrison, “but finally we were interested in actually making things happen.” Team 5 branded Dirtybuoy into an event space, curating a host of Melbourne’s finest baristas, and offering water to passing cyclists. Yet the work stood alone as a sculptural form, attracting visitors from the vast distances of its sight lines, and offering different experiences across the day’s wind and light.

Urban Realities’ most effective works suggest a shift away from Docklands’ preoccupation with spectacle at large scale. The choice of the ten sites, and the sensitivity of each brief, indicate significant potential for future work — not for merely ameliorative public art, but for grounded, engaging public space.