The Tasmanian landscape has long inspired painters with its extreme weather and rugged environment. For Sue Lovegrove, environments such as Tasman Island, a desolate and rocky place off the south-east coast, where native plants and animals rule supreme, trigger what she describes as 'an intimate and personal response'. Her exhibition The Shape of Wind is an attempt to communicate this intense experience and essence of place.

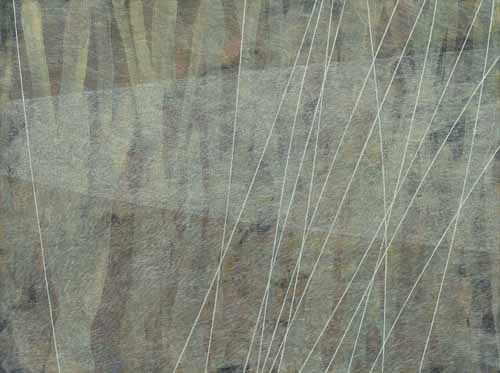

The landscape genre presents a significant challenge to contemporary artists: how do you visually represent the natural environment? Our relationship with nature requires so much more than a distanced figurative re-creation. Rather than pictorially represent the landscape, Lovegrove zooms in on the native grasses that populate the island: plants which she believes ‘are often disregarded or seen as insignificant’. Her 23 intricate paintings, all titled The Shape of Wind, successfully raise the status of these grasses to a vegetation worthy of intense scrutiny.

The word ‘obsessive’ comes to mind. This obsession is evident not only in the labour invested in these paintings, with their innumerable fine lines and intensive layering, but also in the repetitiveness of the subject. While the paintings are all numbered, the earliest in the show is 453, alluding to a much larger body of work. Additionally, the sameness of the subject, method, and patterning, indicates an unusual and extreme fixation.

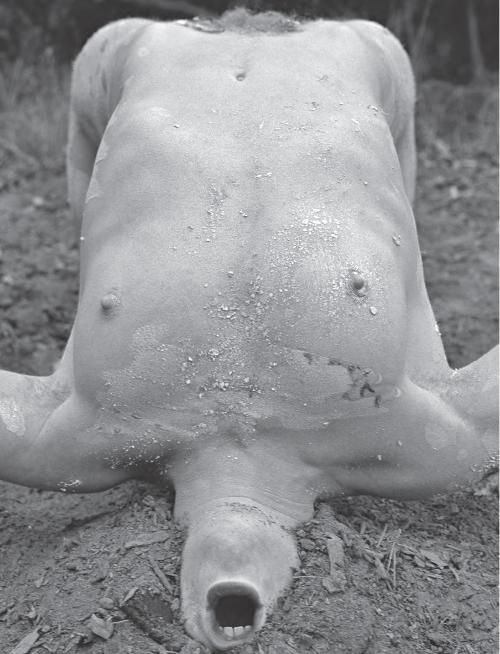

The grass forms are fairly abstracted: colours are not in any way representational and the fine white lines that cross the canvases are highly choreographed. However these paintings manage to capture the chaos and varying extremes of weather inflicted on the island’s vegetation. The Shape of Wind 462 suggests a gale, while the larger 473, alludes to a calmer environment, with drooping and bowed lines.

These are not works that can be fully appreciated at a glance, nor does photography capture their depth and detail. The sides of Lovegrove’s unframed canvases indicate the intense layering from which the rich receding backgrounds of eventual dark purples, greens and browns have been created. Drips of bright yellows, pinks, blues, oranges, and watery purples form horizontal stripes against the white canvas edges like a rainbow spectrum (I would love to see these works hung on a darker background, rather than the ubiquitous gallery white). In the middle ground, what from afar appears as thick translucent lines across many of the paintings, are in fact tiny parallel lines, over which thicker white grass lines bend and arch. Illusion is key in Lovegrove’s paintings, and it is far easier to read the grassy forms from a great distance than up close.

While most works are unframed canvases, on one wall a number of smaller framed paintings hang in a grid formation. The works are simpler than the canvases, and consist merely of thin white ‘grass’ lines on a blue paper background. Compared to the works on canvas, they seem somewhat contrived, and yet it is not so much the relative simplicity of the paintings that disappoint but more the method of display. I understand that for practical reasons these works on paper require long-term protection, however, the frames detract from the simplicity of the works, despite the minimal finish.

In all The Shape of Wind is a tight and well-resolved show, and a welcome alternative to the usually more pictorial landscape paintings shown at Bett Gallery. While Lovegrove’s works are somewhat figurative and still restricted by the traditional rectangular canvas, her obsessive repetition and mark-making, as well as the distillation of the landscape to one subject: native grasses, successfully alludes to her experience of being in the landscape.