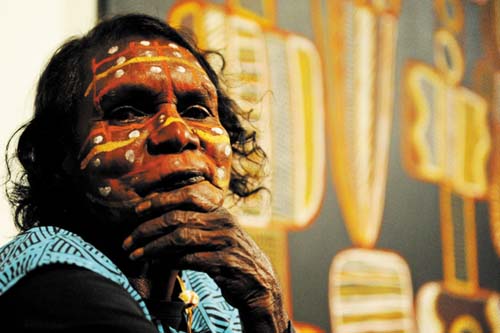

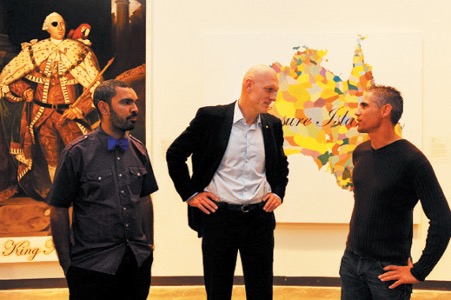

Jean Baptiste Apuatimi is dancing in a Mexican restaurant one km from the White House and gives me the strongest arm-squeeze-and-kiss I've ever felt - the culture warriors are in Washington D.C. and I’m with ten of them for a week to celebrate the opening of their exhibition at the Katzen Arts Center.

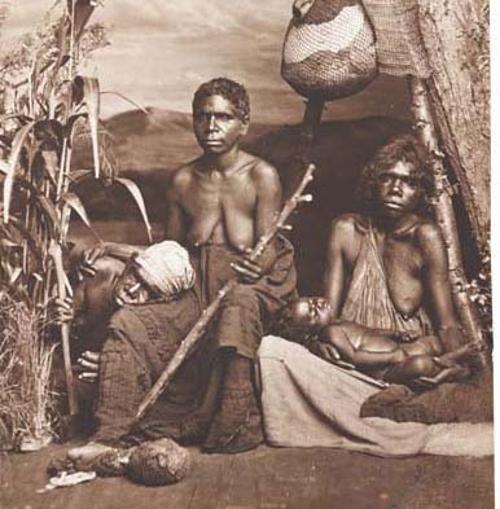

So how does 'Culture Warriors' fit within the history of US exhibitions of Australian indigenous art? Works by indigenous Australian artists were first shown as 'Art’ in 1946 at New York’s Museum Of Modern Art (MOMA) in an exhibition called 'Art Of Australia 1788-1941'. This could seem an unexpected venue because of the associations of MOMA’s 1984 exhibition 'Primitivism in 20th Century Art'. However MOMA should be recognised as being the first venue in America to show Australian indigenous art as fine art rather than as ethnography. Its aim as stated by Margaret Preston in the 1946 catalogue was to be an exhibition: ‘which starts with the work of the aborigines, and ends with the influence of their work as a basis of a new outlook for a national art for Australia’. The assimilation implied by this statement is impossible to reconcile with the distinctive styles developed by culture warriors such as Judy Watson, who on our trip scoured the Thomas Jefferson drawings at the University of Virginia Museum for appropriation into new work. So the tables are turned yet the outrageous reality is that 'Culture Warriors', this multi-million dollar travelling exhibition will only be seen in one university museum in America before travelling back to Australia.

In the American press throughout the 20th Century Australian indigenous artefacts tend to be compared to Native American culture, though urban Australian artists are actually closer to the American civil rights movement. Destiny Deacon installed an eerie room full of golliwog dolls and racist frights familiar to Americans. Yet the local and transnational social critiques that were abundant in 'Culture Warriors' were largely opaque to the American audience because of their lack of knowledge about Australia. ‘Oops, should I be not be calling them Aboriginals?’ one of the major sponsors asks me in the oh-so-corrected Obama era opening – to which Obama was invited but couldn’t come. The Embassy organising the event certainly hoped Obama’s administration took note that Australia, through 'Culture Warriors', which was funded as an official state exhibition, ‘acknowledges a country’s history of state-mandated racism’ the 'Washington Post' reported.

Vernon Ah Kee’s text-based 'not an animal or a plant' clearly refers to the global history of anthropology studying humans and natural history museums exhibiting non-Western people. Yet it was the Jasper Johns reference in Christopher Pease’s 'Target' (concentric circles indicating water holes) that illustrated the 'Washington Post' review. Pease’s typographical overlays represent different ways of looking at land as it is defined as a physical object through elevations rather than as the spiritual places of his Nyoongar people.

Pease described to me his tension or guilt at not being able to ‘believe’ the spiritual, but rather only ‘know’ the stories his ancestors believed. Herein lies the difficulty of painters of ‘country’ being appreciated overseas for more than merely decorative, ancient, or incommensurate patterns. The 'Washington Post' compared the ‘tradition’ in Wamud Namok aka Lofty Bardayal Nadjamerrek’s painting to the work of John Mawurndjul which, in their view, ‘has more in common with 20th-century abstraction’.

Coincidentally 'Icons of the Desert', an exhibition of early Papunya Tula boards, is on at New York University’s Grey Gallery at present. In the context of these two excellent exhibitions, and two questionable contrasts that I will mention shortly, I recall NYU’s head of anthropology, Fred Myers’ chapter 'Performance of Aboriginality' in his 2003 book 'Painting Culture', where he deconstructed the reception of the 1988 'Dreamings' exhibition in New York. Myers identified a twin American preoccupation with non-Western spirituality and religion on one hand and a celebratory and apolitical multiculturalism on the other.

Myers’ theory certainly rings true in the otherwise discerning juggernaut Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the National Museum of Women in the Arts, who each opened exhibitions of Aboriginal paintings this month, work considered not up to scratch by several commentators. Margo Smith, director of the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection Museum at the University of Virginia, voiced ‘concern about these exhibits’ which she says are ‘not on a par with the work shown in Australian museums and galleries’.

Curator Brenda Croft commissioned works from Queensland’s 'ProppaNOW' collective replete with the confrontational edge one would expect from the exhibition’s title. A full hour walk through one of Gordon Hookey’s paintings unravelled his layered references to fighting – a resonant topic with the large presence of military officials invited by the Australian Embassy to the opening. To these audiences in DC the curatorial argument for an indigenous perspective in the culture and history wars was even less evident than in the Canberra hang of 'Culture Warriors', which Museum Victoria’s John Kean described in a telephone interview as ‘rhetorical’, ‘disconnected works’ in a ‘survey exhibition style’.

Cultural attaché Brendan Wall programmed a strong series of lectures aimed at the collection history of indigenous art from Australia and conversations with native American artists. This was a cue to what was different about 'Culture Warriors' – artists were invited to offer their opinions, and were also able to visit local collections such as the Smithsonian and Kluge-Ruhe.

Ultimately live embodiment and performance of ideas are the culture warrior’s best weaponry. Christian Bumbarra Thompson has revived his Bidjara language in new songs that brought tears to the audience’s eyes. And Apuatimi’s body, taut as a drumskin, danced sound into the hundreds of ears in the auditorium.

Ricky Maynard gave a speech as piercingly honest as his portraits and as earnestly researched as his photographs of Tasmanian sites. He concluded: "it’s easy to look but hard to see."