Reflection and criticism surrounding the Sixth APT and its implications as an international event are proliferating and generally well-measured (see pre-emptive strikes in recent issues of 'Broadsheet and Art and Australia'). So to avoid a perfunctory contribution to these debates and as a way of capitalising on my perspective as a young artist this review will focus on a few key works that appear more buoyant in what is an ambitious and disparate assembly of works. I ascribe this buoyancy to the unexpectedness and generosity of the work by Hiraki Sawa and the DAMP collective.

There seems little publicity surrounding the inclusion of Hiraki Sawa. Perhaps this is a result of the artist's lack of emphasis on political forces, customary practices or personal anxiety regarding cultural identity - the common requisite explorations for most APT artists. Alongside Bill Viola, Sawa is represented by James Cohan Gallery and has gained much recognition over the last decade for videos that gently edit miniaturised animals (e.g. camels and elephants) or large scale objects (e.g. aeroplanes and lighthouses) into quiet domestic interiors.

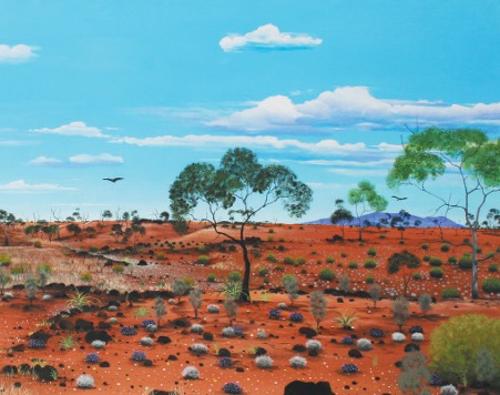

Sawa was commissioned for the APT and is liberally granted the whole of the GoMA’s Media Gallery on the second floor. His large immersive video installation O is a poetic renegotiation of cause and effect exemplified by the appearance of shadows devoid of corresponding physical entities. Three large projections are installed on the gallery floor displaying footage taken from a visit to the Central Australian desert in April 2009: flocks of migratory birds traverse the landscape, the movement of water reflected onto ancient rock formations and a lone branch appearing stark against a mountainous panorama. These potentially idealised moments of nature are recuperated from a typical exploration of the sublime through their combination with some of Sawa’s more characteristically intimate scenes established in an aged, abandoned interior. In these delicately surreal moments, the full moon rises beneath a chair and tiny lighthouses adorn quiet corners.

These large projections are offset by works on ten smaller monitors set into the walls showing neatly looped footage of perpetually spinning objects (tops, lightbulbs, bottles and so on). These works are economic instances of Sawa’s larger interest in circular movement. Also connecting these works is an immaculately recorded and compelling sound track by Dale Berning emitted from a series of consecutively rotating speakers that speed up and slow to a stop, simulating the movement of a spinning top. O appears to address a more expansive terrain than his previous works (some of which are shown in the Children’s Art Centre) and its intimate physics eclipses a number of other immersive works in the show.

Also included is a work by Melbourne collective 'DAMP’. For APT6 DAMP has remade 'Untitled' 2007, an oversize faux marble plinth supporting a motley collection of chairs accessed through an interior staircase. Throughout the exhibition this arrangement will be put to use as a meeting place by local groups invited by DAMP. Their selections, including the QAG installation team, the Brisbane Knitting Group and local Artist-Run Initiatives amongst others, reflect a democratising spirit that is central to the ethic of the collective. The physical and conceptual elevation of the group process as a creative force is so literally presented here it may seem a little elementary but its gargantuan size and farcical DIY marble texture point toward something much more playful.

In this incarnation of the work DAMP has fitted out the inside of the plinth as a spacious cubbyhole filled with an accumulation of effects from their Melbourne studio including badly executed monochromes, a tea station, fake vomit, bottles of DAMP Estate Collaborative Sauvignon and a copy of Sharon Goodwin’s high school text 'Chemicals and the Artist' complete with a gas-mask clad Mona Lisa. Astutely recognised and presented, this studio/lounge is the location of the external space of their collective process, inclusive of art and non-art related objects and discussion. This space is also a gesture extended to the visitor, a welcome retreat from the sanitary and dislocated space of the gallery, a gesture that is all too keenly taken up by some visitors: I can’t help but notice that the No Access vinyl instruction applied to the gate that leads to the top of the plinth has been amended to read No A---ss. This kind of larrikinism is a key feature of DAMP’s work and tends to disfigure (though not entirely) the overstated relational aesthetics readings to effect a much more idiosyncratic and exciting set of propositions.

To speak generally about the APT, the sparseness afforded by the large galleries assists in what is a sophisticated arrangement of works. My one reservation is with the acoustic proximity of Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan’s lively kids’ activity 'Inflight (Project: Another Country)' with the meditative space of Ayaz Jokhio’s 'a thousand doors and windows too...' . Several smaller project-based exhibitions ('Mapping the Mekong', 'Vanuatu Sculptures' and the 'Mansudae Art Studio') lend the show moments of curatorial and geographic specificity that successfully relieve the interpretive anxiety induced by the overwhelming expanse of work.

This year’s APT is expanded in both scale and geography and is newly inclusive of work from the Middle Eastern nations of Turkey and Iran. One might be critical of this move as sign of the diminishing import of the regional focus but perhaps these additions are a strategy for the renewal of a project in danger of monotony after exhausting its initial assertions. The APT’s dedication to an expansion and democratisation of the conditions of ‘contemporary art’ set out by other Biennale/Triennial events can sometimes make for interpretive experiences that are much akin to a conversation involving a beginner language dictionary. These experiences can be overly explicit and didactic. In singling out the work of Hiraki Sawa and DAMP I mean to point toward the cultivation of an openness to what is unknown in our interactions with the world. These works initiate an indeterminacy that reinvigorates our encounters with cultural difference.