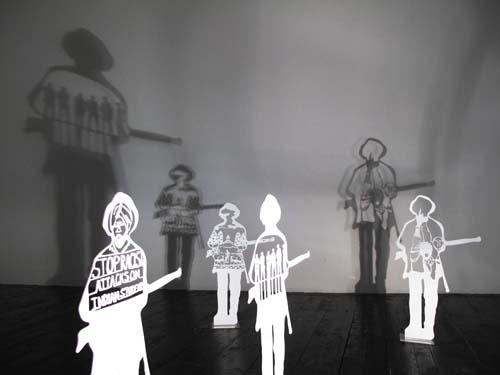

Vernon Ah Kee: Sovereign warrior

If I didn’t have art as an outlet, I would be angry, really angry, and frustrated. Aboriginal people in this country are angry to varying degrees. Some are very, very angry; some have it on a low simmer; some hardly sense it at all. At different times, I experience all those things.