Indecorous Abstraction is an exhibition of abstract paintings (and purportedly abstract paintings - but more on that later) by fourteen women artists, curated by Margot Osborne. That very fusty first term in Osborne's title - try saying it without sounding like a Victorian prude - sits oddly with the austere twentieth century notion of abstraction in art. But before you get the wrong impression, it should be said that Osborne exercises a particular and idiosyncratic conception of the indecorous here. As she writes in her catalogue essay, these paintings are ' 'indecorous' only in so far as they transcend 'décor' and the decorative'. The idea is that by putting together a group of strong abstract paintings by women of varying cultural backgrounds and generations, the stigma of the 'decorative', which Osborne believes has dogged abstract painting by women, may be thrown off.

So what is Osborne's beef with the decorative, and what alternative is she posing? As she puts it elsewhere in her essay, 'the difference between a significant abstract painting and mere 'décor' art comes down to the painting's material embodiment and transmission of the artist's perceptions, emotions or vision'. Earlier, she mentions, 'the artists' use of organic line, pattern and repetition to move beyond mere decoration and design... to create contemplative rhythms, resonance and mesmerising fields of materialised energy.' While Osborne's references are broad - she makes a passing mention of a spiritual dimension in some of the works - and sometimes daffy - she refers to a psychological study that has shown that Mondrian's abstract paintings cause 'a sharp peak in brain arousal' - her general focus seems to be on abstraction's formal and expressive qualities.

Her appreciation of abstraction, in other words, is largely confined to those qualities defined by Modernism as of value. Similarly, her denigration of the decorative - for lacking those same qualities - also repeats a Modernist attitude. Much of the show Osborne has put together reflects this superannuated rationale - but interestingly, a number of her inclusions offer some resistance to it.

Angela Brennan's paintings, for all their attractions, fall into the first category. They are bright, colourful, gestural works that appear to owe something to Sonia and Robert Delaunay. The titles, like the paintings, are warm and whimsical - Every night about this time III and In the sphere of love (both 2001). Ildiko Kovacs and Kari Bienert also look like pleasure seekers. Kovacs fills her canvas, Leaning to the left (2002), with an unravelling, vigorously wiry form. Bienert's three paintings are mosaic-like patchworks of colour, but her inability to control a too wide variety of colours and tones deadens what is intended to be a pleasant effect.

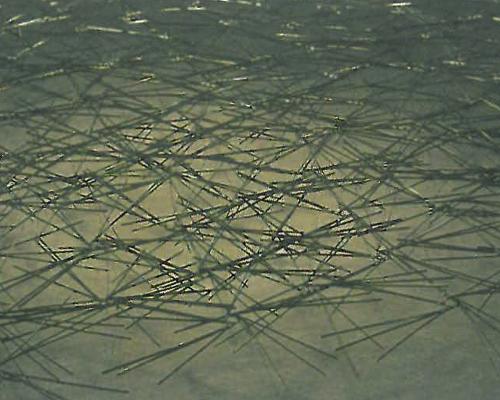

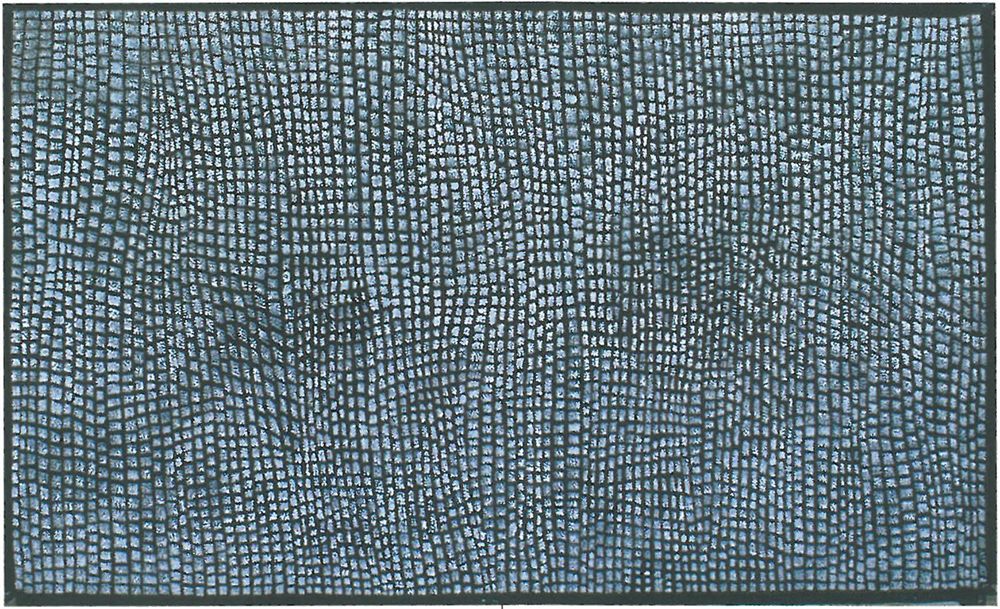

Wendy Kelly's and Savanhdary Vongpoothorn's works are comparatively austere. Kelly's blue monochrome 2001/62 Diamond (2001) features a matrix of thread-like lines laid over a diamond shape. Her work is subtle, minimal (but not 'minimalist' as Osborne states in the catalogue) and contemplative. Vongpoothorn's Untitled (2001) was apparently made by perforating the canvas and applying paint to the back, which bleeds through to the front in glowing, shimmering matrices of colour that hover over a dark, brown ground. Cathy Blanchflower's canvas Orbital (Atlas XV) (1999) is, according to Osborne, an optical painting. As someone immune to the effects of 'magic eye' puzzles, I withhold judgment on what looks to me like a large, dull geometric work.

Marion Borgelt's Psyche of a Landscape: The Wimmera Plains (2000) pares back its motif to the sparest of geometric forms: light cross-hairs centred on a dark, reddish ground. Borgelt's paintings have a romantic quality, harking back to a moment in the '70s when painters such as Barry Goddard adapted the language of post-painterly abstraction to interpret the Australian landscape. Aida Tomescu produces my favourite painting of the show - Ithaca (1999) in which a thick, dark greenish-greyish paste of an almost geological texture obliterates all but a few touches of colour that remain at the canvas' edges.

Borgelt's and Tomescu's focus on landscape raises another issue - that a number of paintings in Indecorous Abstraction are not in fact abstract. This is most clearly so in the case of paintings by Aboriginal artists, Rosella Namok, Dorothy Napangardi, Mitjili Napurrula, Gloria Petyarre and Angelina Pwerle. Namok's painting Yiipuy and Kungkay: calm weather (2001) is of particular note. It's a large, glossy, brusquely sgraffitoed panel that adapts traditional designs and colours into something slick, fast and shiny.

Is Osborne's inclusion of representational works a problem? Not so far as it provides a pretext to see work like Namok's. But it is a problem if it encourages us to see such works as abstract. The trouble with placing these paintings alongside genuinely abstract works is that it encourages the viewer to focus on what the works have in common - certain superficial formal qualities - while eliding the points of difference - the different cultural, social, ritual and aesthetic contexts from which these works draw their distinctive meanings.