Arte Povera, a movement identified by curator Germano Celant, exploded as a reaction to a number of cultural specificities – post-war Italian politics, an aggressive urge to explore and experiment with the art object and to shatter complacency. This almost political agenda, combined with constant experimentation and action, is signalled immediately by Alighiero Boetti's embroidered map marking zones of political geography. Politics, energy, force, change and dark, wry humour - all these elements are at play in the Arte Povera works.

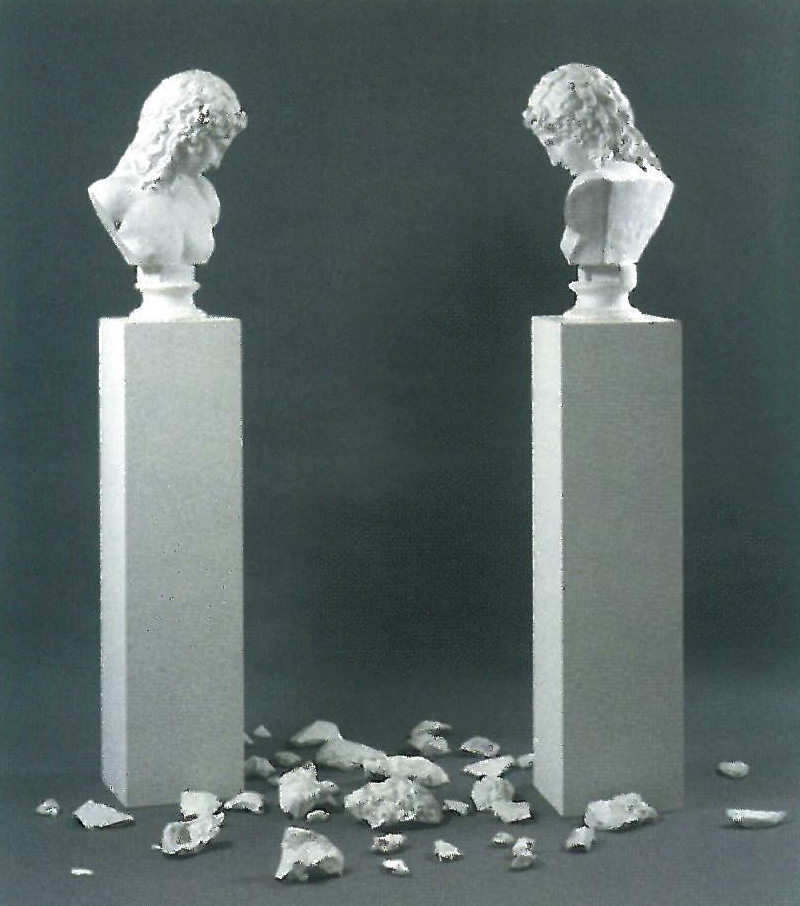

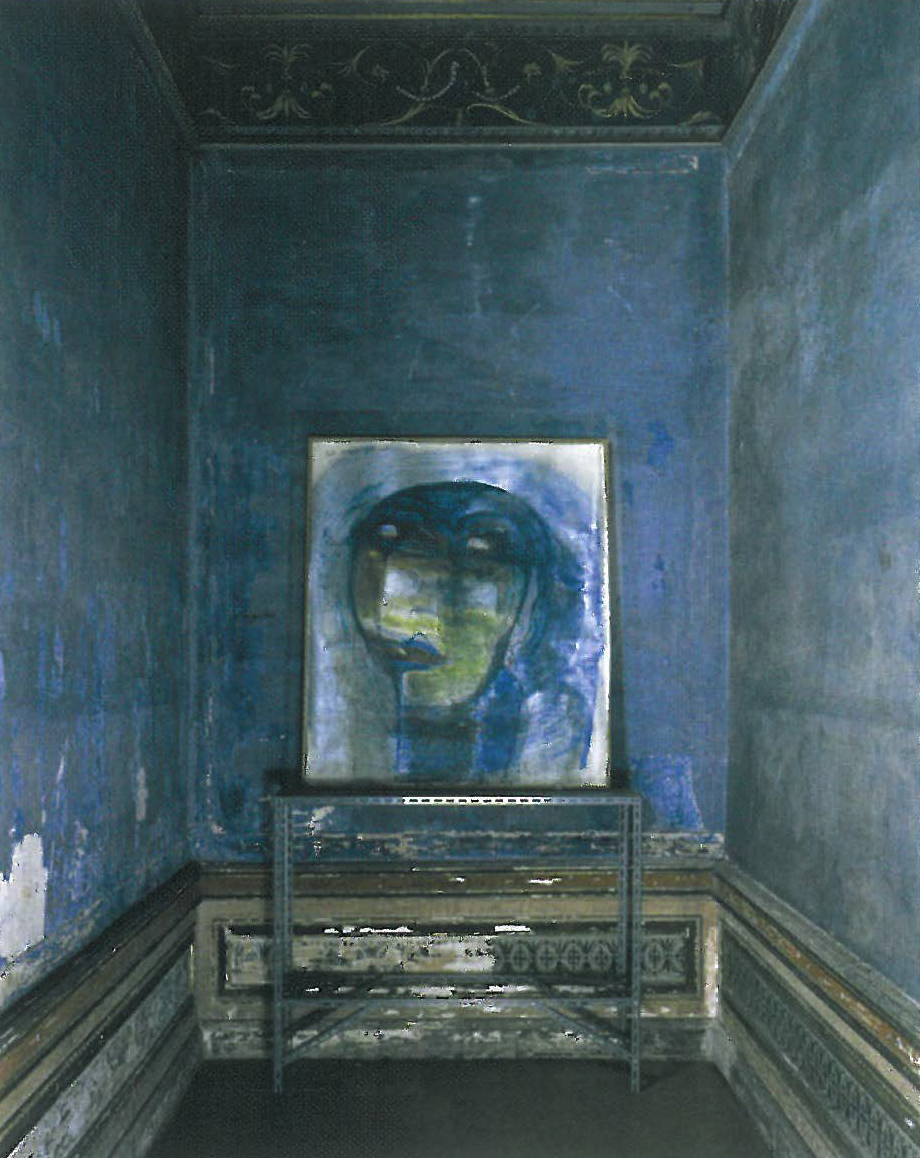

So why does this exhibition feel strangely lifeless? Michelangelo Pistoletto's Venere degli stracci [Venus of rags] perhaps holds some answers. This work, a plaster Venus, facing, almost embedded in, a mountain of rags has heavily graced the exhibition publicity material. Bringing the discarded into a sharp aesthetic focus, Venus acts as a ready signifier for Italian experience/s. The sumptuous image reproduced in the catalogue has Venus and her rags piled up intruding on a faded palazzo wall; signalling a palimpsest of cultural experience. Yet Venus in the MCA space, against her blank white wall in her clean art space is lessened; she becomes, oh dear, something cute. This context may honour the work but it also diminishes its impact. It is not that the Arte Povera works cannot exist outside of an Italian context; but they do require a space, an environment that energies them rather than engulfing them (coercing them) into the art establishment.

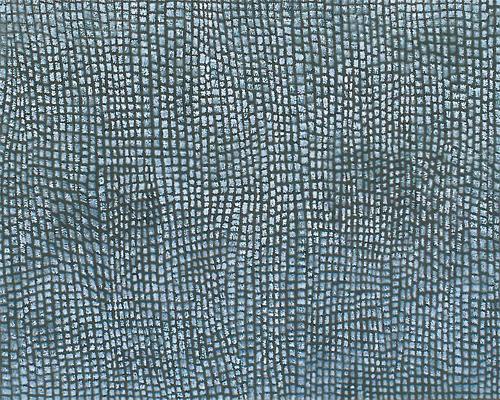

That is not to say that the MCA has not been generous in their presentation of this exhibition. Arte Povera: Art from Italy (1967 – 2002) is well articulated and broad in scope; there is nothing stinting about either the space or attention given to the work. Installation works, relying so critically on the experience of the body in space, can be particularly hard to curate as they ask for a moment of direct interaction for the viewer. Respiare l'ombra [Breathing Shadow] Giuseppe Penone's exploration of the natural, corporeal and artificial, does successfully engage the viewer, making it in this exhibition something of a stand out. The heady scent of the laurel leaves held behind mesh are a delight – we absorb the scent into our own lungs mimicking the gold leaf lungs that sit against the wall, the body exposed.

The space of Pier Paolo Calzolari's La casa ideale [The ideal home], a "palace of memory" constructed of felt, text, ice and featuring, occasionally, a pure white dog, also engulfs its audience, catapulting them into an artificial yet tangible environment. (Watching people in this environment is a pleasure – some awed, others entertained and amused. It also makes clear that the most effective pieces in this exhibition are those that transcend the gallery space through dominating it). Mario Merz's Architettura sfondata dal tempo [Time Based architecture – Time-debased architecture] acts in a similar way; the igloo like shape offers a shelter, the jagged edges and the intrusion of the painted bison erupting into the space disrupts our ideas of safety. This is an art with impact and immediacy.

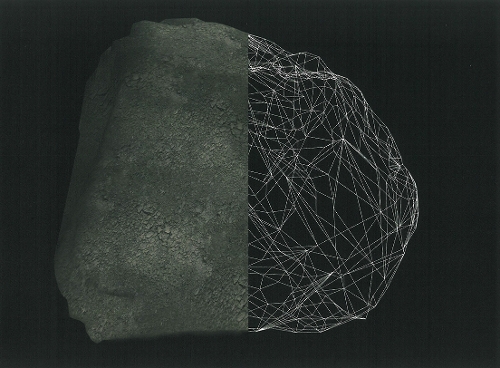

A crucial part of the presence of Arte Povera work relies on this impact, on surprise. The surprise of the fragile and heavy in a constant tension, or of the use of unexpected natural materials. Jannis Kounellis' work's reflect this– piled coal sullies the white cube; steel panels and dirtied clothing hang as a crucifixion triptych, the earthy is ordered in these meticulous constructions. Giovanni Anselmo's Senza titlo (struttura che mangia) [Untitled (Eating structure)] creates an almost shocking tension: lettuce sits between two granite stones, if the lettuce wilts then the stone will fall.

And yet, somehow this exhibition never seems to fully demonstrate the sheer vitality of Arte Povera. Viewing Gilberto Zorio's Barca Nuragica [Boat of the Nuragh] a constructed bullrush boat sweeping through space, lit and slightly charred by intense heat and light, or Stella di giavellotti [Star of Javelins] the expectation is confrontation, as though the javelin is directed at us. These forceful works which are meant to threaten (offer?) violence, are reduced to little more than an intellectual pleasure. Likewise, Marisa Merz's violin moulded in wax is made charming, the sense of mystery summoned by the wax sitting in water, diminished. It is not that the art is made meaningless, rather that meaning has shifted, the works becoming passive objects rather than energetic signals to action. This is a deeply sincere overview of the Arte Povera movement, sadly though the sincerity lent by the gallery space has washed out some of the very elements that makes the movement so powerful.