Neo Tokyo, featuring ten young Japanese artists, and one collective, provides a fascinating survey of contemporary Japanese art, within the specific focus of engagements with the urban experience. While many of the works deal with particular Japanese concerns, notably the sculptures of Kenji Yanobe which negotiate post nuclear tensions employing symbols from Japanese anime such as Astro Boy and Godzilla; the anxieties and pleasures of the urban space, played out in Neo Tokyo, are universally resonant. Negotiations between conformity and individuality, key issues in this exhibition, are of relevance to any urban dweller – with Tokyo a particularly potent space for this tension.

Commenting on conformist models, Shingo Suzuki's 1/1 references a popular board game, 'The Game of Life'. This tidy piece of social engineering is 'won' when pegs representing spouse, family, possessions are fitted neatly into holes. Suzuki has enlarged these pegs to six feet, the height of the average Japanese male. They are however left white (unlike the 'Game of Life' where you are gender colour coded – presumably in case of ambiguity). Displayed in a sterile space these pins may perhaps offer an opportunity to construct our own colour coding and a different method of travelling the board. Or perhaps a bleak acceptance of the social role in which even colour has been washed out.

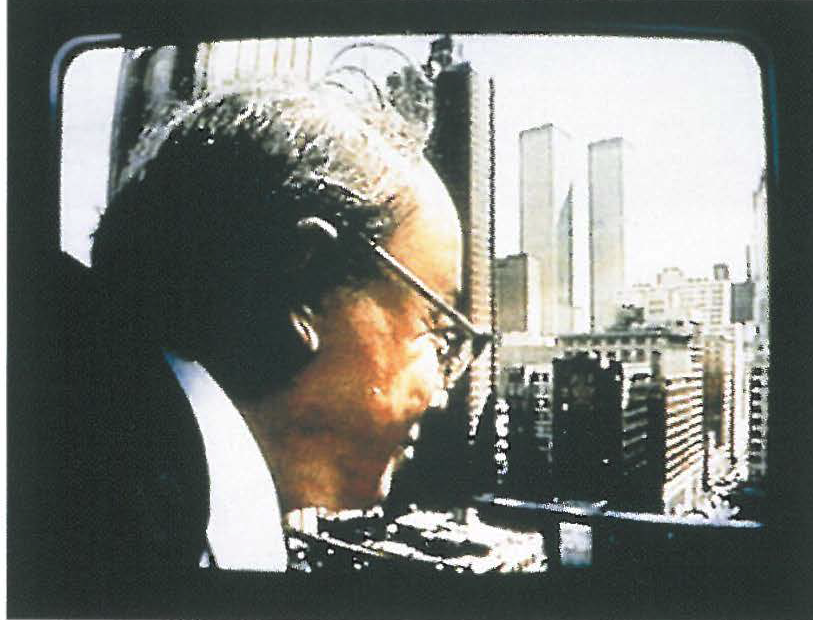

Both Momoyo Torimitsu and Miwa Yanagi explore the individual reduced to corporate symbol. Torimitsu's Miyata Jiro is a delightful conceit, playful yet critical. A life-sized battery-operated figure of a Japanese salaryman, Miyata Jiro crawls through major metropolises tended to by the artist in the guise of a nurse, and the videos of his various excursions (or perhaps incursions) are displayed with his commercial endorsements. Both entertaining and unsettling, the crawling salaryman, the perfect corporate cipher, not only represents the anxieties of the Japanese businessman, but perhaps our own corporate fears. He is, after all, crawling through our spaces, almost as though moving into battle. (And to answer the question drifting through the gallery: No, the crawling salaryman is not deliberately meant to look like our Prime Minister. But yes, it does make you think.)

Miwa Yanagi's's luscious digitally generated consumer environments, populated only by elevator girls (beautiful, young Japanese women identically dressed and employed by department stores) are as enticing as the most seductive piece of advertising. Utopia or dystopia, certainly these spaces are beautiful, but their beauty is uniform and desire has been commercially packaged.

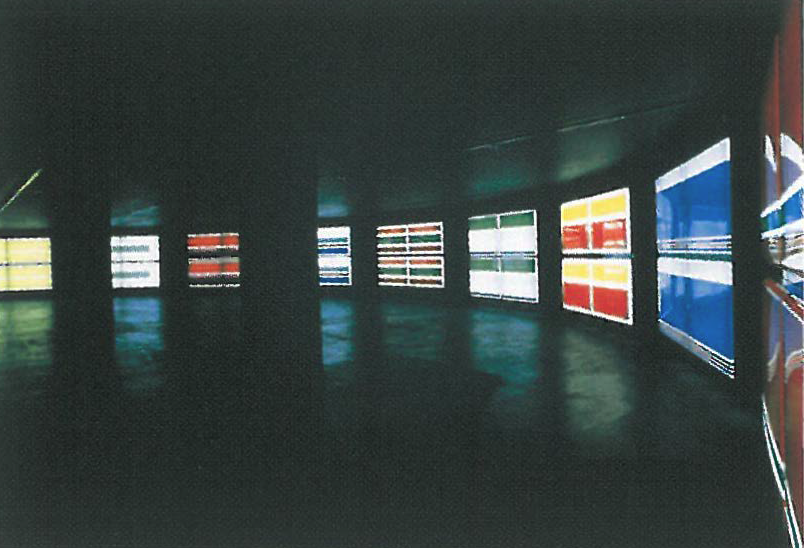

Beauty is something I imagined would be rare at 7-Eleven, yet Masato Nakamura's neon abstractions are quite beguiling. Using the corporate colours of convenience stores, these light boxes act as signs for the city – enticing, they welcome us in, providing colour coding for our choice of consumer experience.

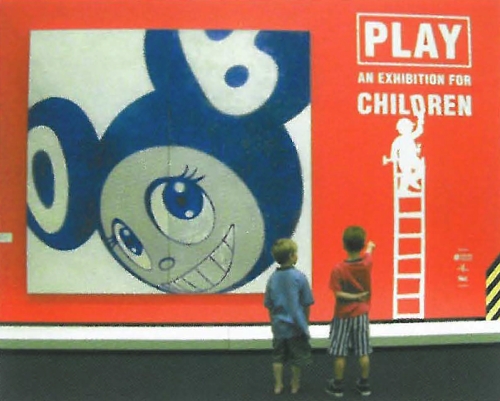

Within the metropolis, however, alternative spaces exist – memory, dreams, the fantastic. Taro Shinoda's Personal Satellite Project, composed of rocket and satellite models, is the artist's own method for transcendence. These almost totemic models offer to transport us, providing means of escape. The Little Pilgrims (Night Walking) of Yoshitomo Nara reference cartoons and dream worlds. These five stylised childlike figures, almost saccharine sweet in lamb's ears and nightdresses, mimic the kawaii (cute) culture of Japan. And in the same way that a store filled with Hello Kitty merchandise is unsettling, so Nara's illustrations and figures of these kawaii children disturb the viewer. The enticing exterior may hide menace; it could be a dangerous seduction.

Myeong-eun Shin's little pink poodle sculptures surrounding a mother and father pair, complete with ridiculously stylised locks, are cute indeed, yet they also represent control and conformity. Like a fever-induced dream of a dog breeder perhaps, these are perfect identical specimens, manipulated and modified to the point of the ludicrous. And yet the delightful eccentricity of the poodle shape shows that perhaps even the most conformist and manipulated experience may in fact be simultaneously individualistic and creative.

And The Lemon Project of Satoshi Hirose brings us back to our own corporeality, relocates us as individuals in both gallery and urban space. A passageway filled with lemons creates an extraordinarily sensual environment. As we experience the evocative smell and the crazy beauty of a room full of lemons so we are reacquainted with our senses. And imagining biting into a lemon, that sharp, sweet, sour taste, at once both mouth-watering and repellent, seems an apt metaphor for the urban experience as so intelligently explored in this challenging and yes, refreshing exhibition.