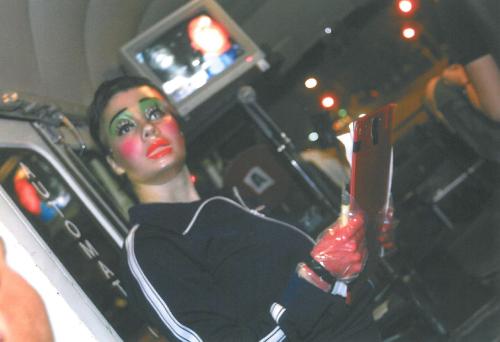

I well remember my first sight of William Yang's photography. It was at the original Australian Centre for Photography in the 1970s, and Yang's images shone like scandalous jewels on its dark walls. 'Jewels', because was ever photography so brightly coloured, so intense, with its multitude of small images crammed on the walls? 'Scandalous', because this was the first public outing of the Sydney Gay Scene at the height of its self-indulgent hedonism. To make these images of such outré intimacy, this man had become invisible and his camera appeared to be an extension of his ever-watching eye.

The Gay scene was/is his culture, but Yang the observer was also from the start, Yang the interpreter. Those early images captured the frenetic pleasuring of men newly liberated by the sexual revolution, while later photo essays recorded the slow grief of a community as it learnt to cope with death through AIDS and different ways of showing love in mourning. Throughout the decades Yang has refined his technical skill and added personal touches, such as his hand-written annotations to images, which turn many of his photo-essays into extended diary entries.

What then is the difference between the early work and this large recent survey? 'Obsessions' still seems an appropriate key-word. Each subject is savoured, and then worked at, reduced to its essence, and still enjoyed. Many of the subjects are familiar from early exhibitions - Bondi Beach, the Gay scene, parties, food, and Chinese heritage. But there is more. These are works of a mature observer, who selects the objects for his camera with all the discrimination of an epicure.

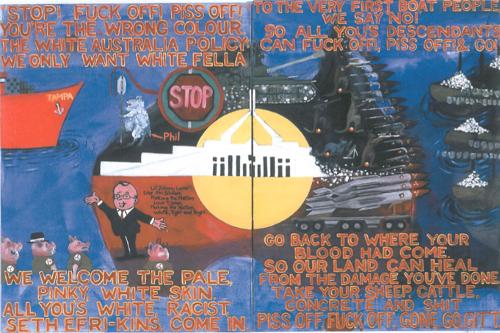

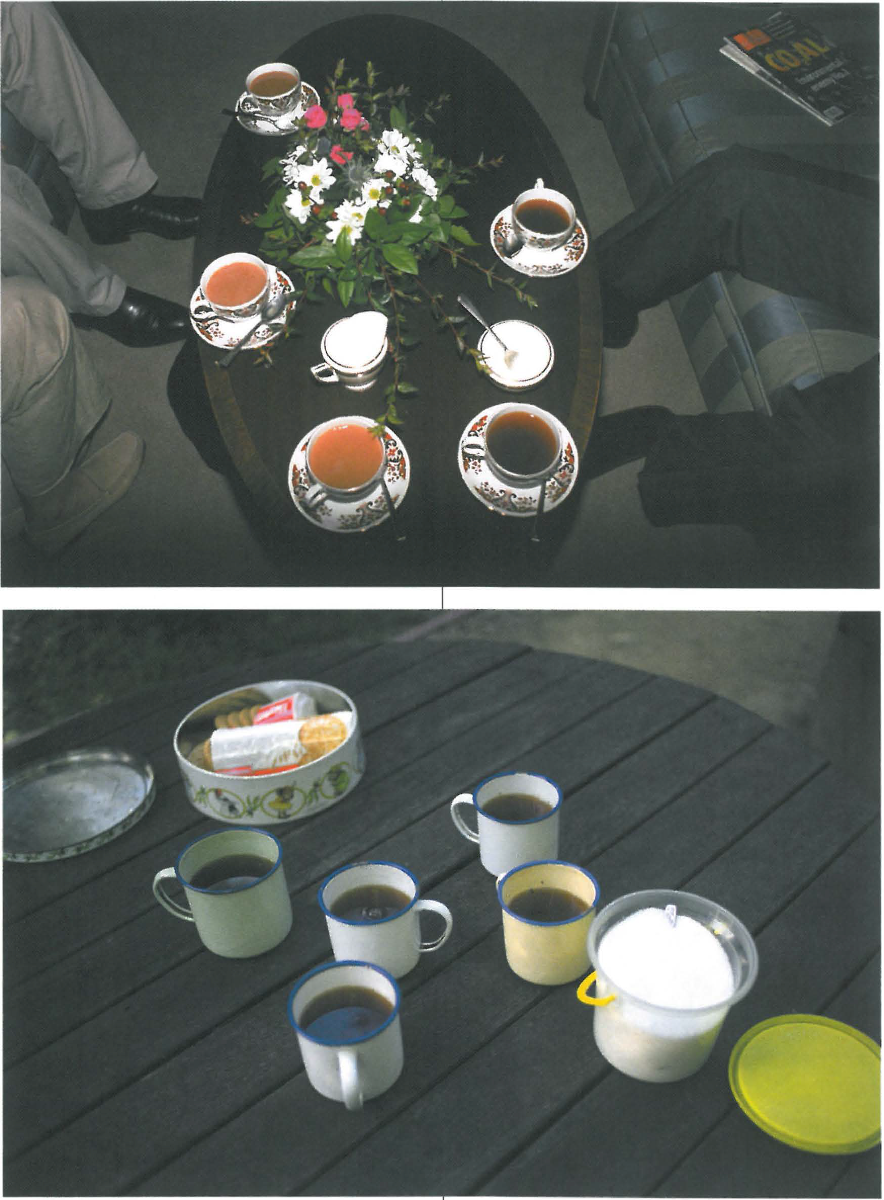

Enamel mugs and sugar on a rough wooden table are enough to evoke Morning Tea, Near Nerang. A pair of hands cutting a mango makes the intimate mood for Breakfast with Scott. Yang understands that it is the small gestures that make the large picture perfect. He has written many times of his self-awareness as an outsider, and it is perhaps this status that makes him such a brilliant observer. Tea with the Deputy high Commissioner, London, with its flowers, fine china cups, milk jug and trouser-legs encapsulates all that is precious about the London diplomatic circuit. Yang always sees more than others, and records it with deadpan accuracy.

Food is an effective device for coding a society. From the banality of the lunch special at a roadhouse in Western Australia to the huge fish in ice at markets at Bergen, the cheese platters of Paris, the cream cakes of Germany and the Peking Duck of Beijing; food defines how people live, and how they value themselves.

Yang's work almost seems to flow between apparently opposing sets of values. Sometimes his society is one of performers, the half-seen inhabitants create personae either for themselves or others. They are aware of how they look as they live. But then he will cut through to essential truths, to the results of performance, such as his stark images of the Holocaust, or his images related to the AIDS pandemic. After all his images of food and Australian native life, including an incredible postcard image of a koala, and some classic landscape photographs that would do the pictorialists proud, he is able to confront the viewer with a photograph of roasted echidnas. Cute can also be eaten.

Some of Yang's most effective images do not rely on exotic travels or unusual content. Instead it is his understanding of the simple conjuction of shape and form. Cloud patterns floating devoid of context; flags at Bondi Beach against a perfect blue sky. These are images of a world of perfect beauty, where pleasure comes not from artifice, but can be seen by the all-observant eye of the artist.