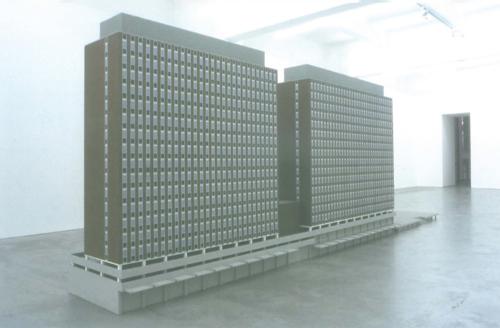

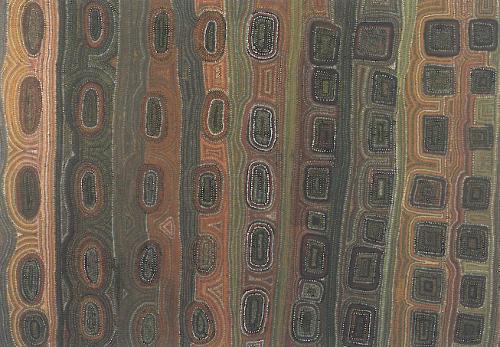

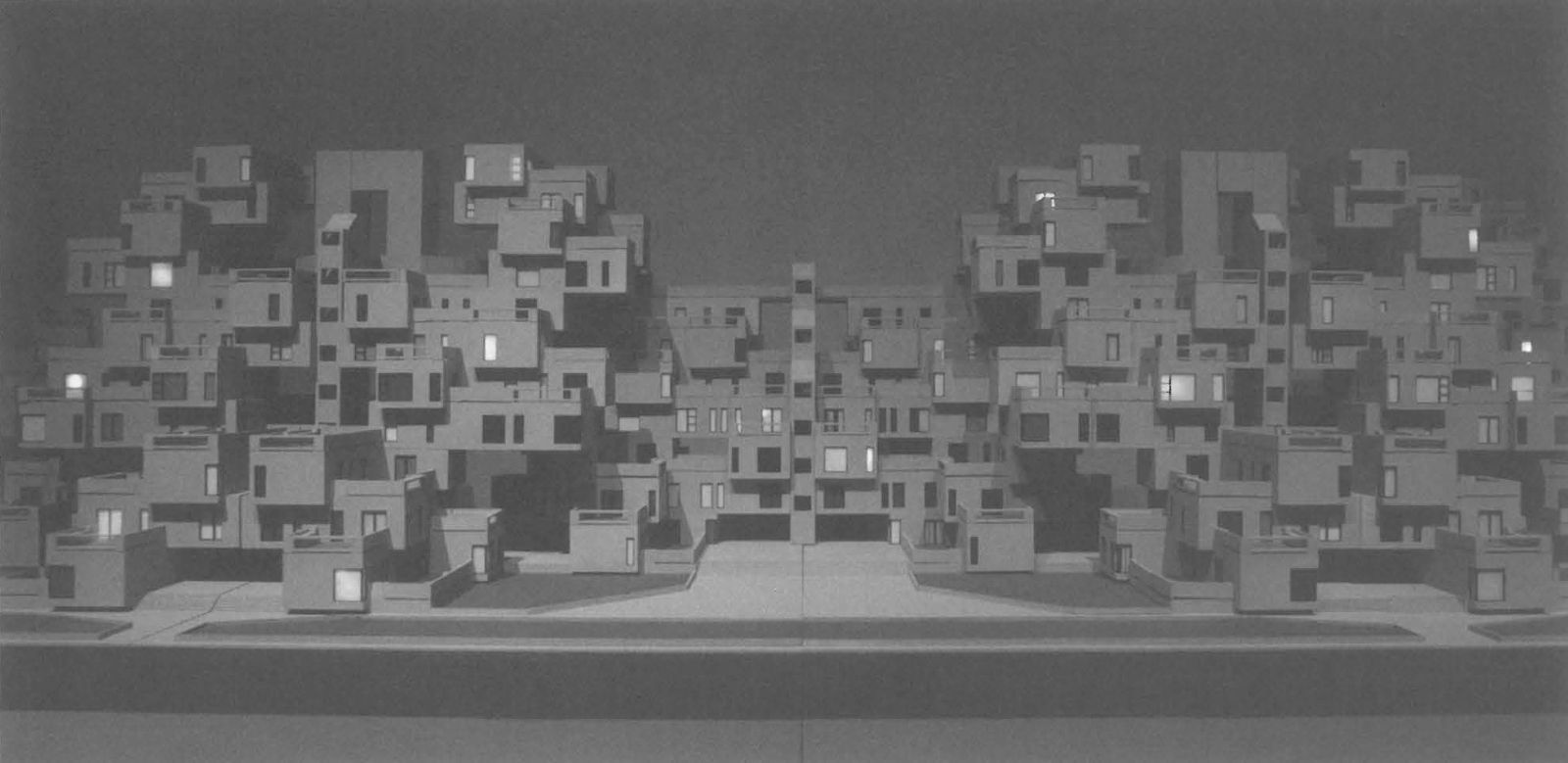

Callum Morton's sustained interest in the relationship between people and their built environment continues in his new work Habitat. The work is a 1:50 scale model of a mass housing project built by Moshe Safdie for the 1967 Montreal Expo. This concept for low-cost community living stacked sixteen different modules to create living spaces varying from bachelor pad to a family-sized suite. The project went massively over budget, and sited on the outskirts of Montreal without the amenities that Safdie had originally planned, the complex was not such a desirable place to live.

The real Habitat was thus a sort of model in its very execution: a prototype whose potential remained unfulfilled. It is against its noble dreams of community living (which, by the way, Safdie optimistically views as '&possibly the only utopian project to have been a real popular success') that Morton moves in his imaginary tribes of disruptive residents.

Departing from Morton's previous works, where the internal voices of conflict threaten his pristine modernist models, the chaotic sound and light routine of Habitat almost matches its architectural form. There is something undeniably human about the haphazard-looking facades, more Native-American Pueblo than J.G. Ballard High Rise.

So while Mies van der Rohe would have gasped in horror at Morton's curtains on the Farnsworth House in International Style (1999), one suspects that Safdie wouldn't mind the coloured contents of each miniature apartment in Habitat, that turn the otherwise neutral façade into a flashing Christmas tree. As an apartment illuminates, a soundtrack describes the internal goings-on of its occupants: alarm clocks, farting, flushing, kettle whistles, burping, door slams, cars starting, conversations and arguments, a giggle that turns to complete hysteria. As the evening progresses, the screams and howls of a schlock-horror film take over the dwellings.

The precise goings-on might be difficult to decipher, but the time-lapse effect of a day is assisted by a wash of coloured light on the back wall indicating the cycle from dawn to dusk. Habitat has a twenty-eight minute cycle, the same ratio to 24 hours as the model's measurements are to the real structure. Shrunk in time and space, the perpetual routine of their lives in fast-forward is as funny as it is depressing. The effect is no advertisement for apartment living.

Except for a tantalising peak through a portal in one gallery wall, the frontal orientation make the viewing experience of Habitat quite passive. This sense of being a spectator means that the work lacks some of the sly surprise of other Morton installations.

Habitat offers what initially seems to be a voyeuristic experience, letting us hear and see the lives behind drawn curtains. But of course our voyeurism is largely unfulfilled. In fact, perhaps the drama is not as it seems. Maybe, rather than being privy to the secret goings on of hundreds of private lives, we are witnessing that other concealed life of domestic space – the eternally flashing screen of the television.