Every day a film festival is on somewhere in the world. The Adelaide Film Festival stands out from the ruck by commissioning films and projects, and by a broad emphasis on the celebration of multiple aspects of contemporary screen culture from advertising to cartoons to computer gaming. The second AFF had more extra features than a new car making it certain that each person that attended was able to design their own Festival – whether making movies on their mobile phone, getting down with interviews, workshops, debates, music videos, animations or shorts, going to the Australian International Documentary Conference or simply looking at lots of films. All films were Australian premieres, many were world premieres.

The film that set the tone for me was The Ister, made on digital video by Melbourne-based David Barison and Daniel Ross, a 204 minute documentary about the Danube and its journey through Europe from its mouth in Romania to its source in the Black Forest. Basing itself on a series of lectures by Martin Heidegger on a poem by German poet Hölderlin about the River Danube the work is a language- and concept-heavy journey. It takes us through many different regions of contemporary Europe, the war-torn, the once communist, the patched-up, the bombed, the heaped with history and memory. It includes interviews with philosophers Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Jean-Luc Nancy, Bernard Stiegler, and filmmaker Hans-Jürgen Syberberg. The film raises issues of home and place, culture and memory, technology and ecology, politics and war in highly complex configurations and specific sites.

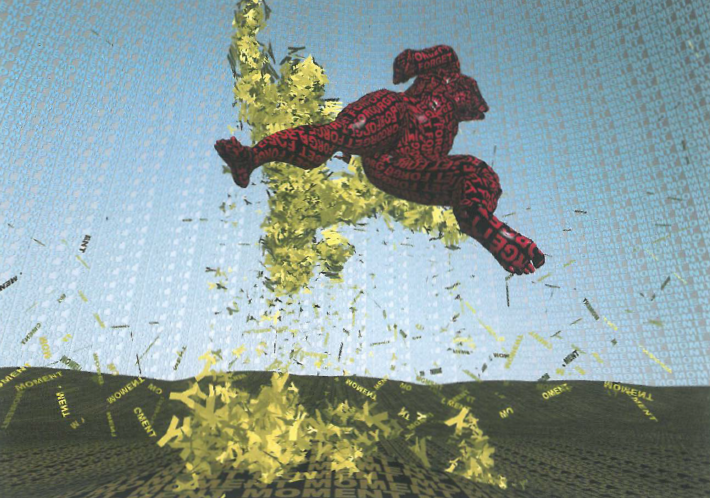

This specificity was missing in Transcriptions the four-screen video installation commissioned by the AFF and made by David Evans and Garry Stewart, with the assistance of many others. The digital environment of the dancers is deliberately placeless and their archetypal battle choreography is global-nowhere techno-space. Yet there is something quaint and out of date about such a simple vision of the future when today identity and history are clearly seen as highly significant rather than simply erased by technology. Perhaps it is best viewed as a work in progress. The overarching ambition of the work - 'to make concrete the notion that language is the frame through which subjectivity and lived experience is perceived' is so abstract that it lacks resonance.

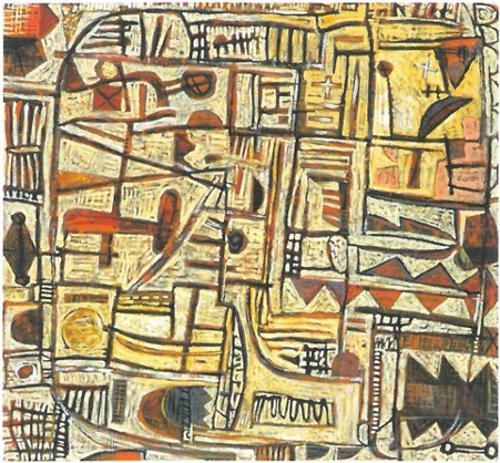

In contrast Chinese artist Wang Jianwei's videos are so specific to China that particularly in the case of Ceremony, a video of a major stage multimedia performance held in Beijing and Brussels in 2003, more information could usefully be included. This performance has some similarities to Evans and Stewart's work in using dancers and projections but in Ceremony there is a sense of immense historical events being reviewed and made over symbolically rather than a semiotic theory finding an illustration.

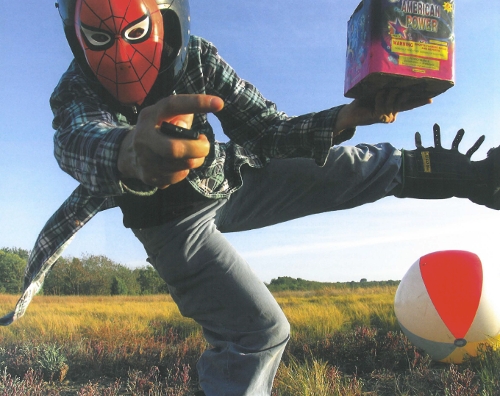

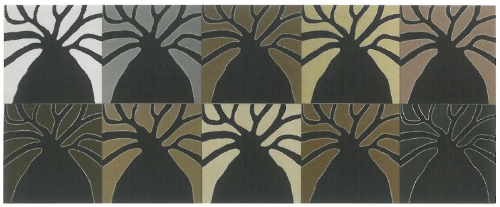

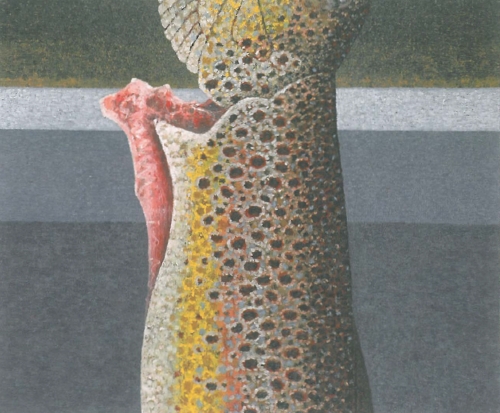

Jianwei has said: 'I want to experience comprehension and incomprehension at the same time, a balance between doubt and conviction, being pulled by two extremes.' Spider is a two channel video, a symbolic critique of the intensive development and surveillance happening in China at present as well as a study in contrast between faceless bureaucratic men going through repetitious tasks and the peasants who do the work of building and labouring (the term peasant has survived modern times in China and denotes not just country people with rudimentary education but the peasant power which enabled the Cultural Revolution to happen). The second screen shows the faces of these people simply looking and smiling into the camera. This is effective as the openness of their faces introduces them to us as individuals.

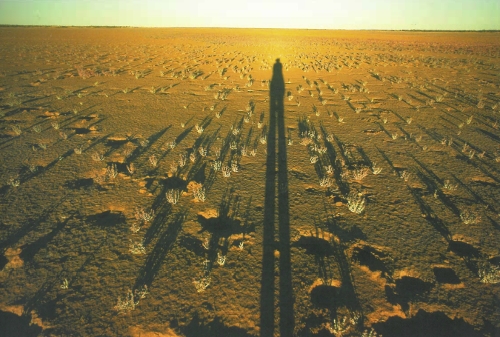

In the third video Square featuring Tiananmen Square on a public holiday when people come from the country to take photographs of Chairman Mao's portrait it is again the peasants who provide the best content. There is a man with a performing cat on his head, there are two brothers in identical shirts, one of whom is removed from the video limelight by his brother but returns, and a woman who snarls at other people then smiles for the camera. It is the sense of humanity provided by the documentary elements of Jianwei's work that is illuminating rather than his more formal theatrical interpretations of conformity and exploitation but maybe this contrast is needed for each to be seen clearly.