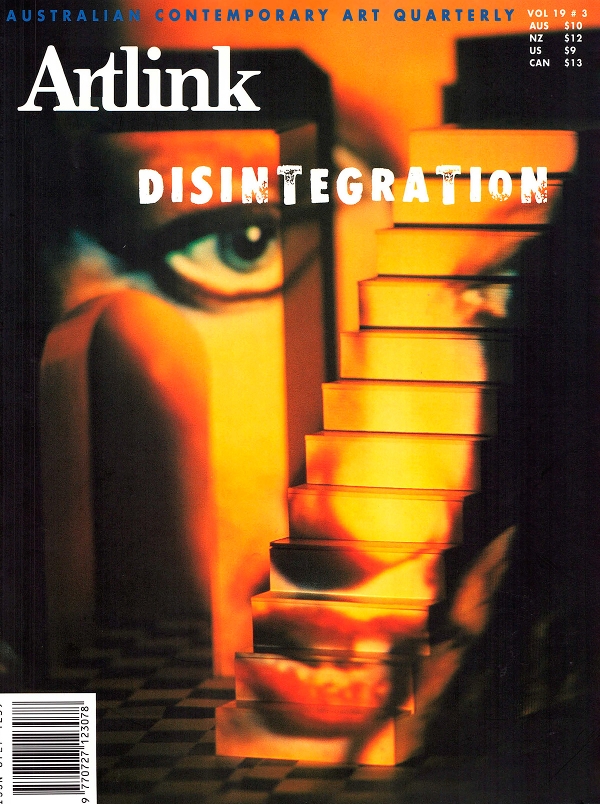

Disintegration

Issue 19:3 | September 1999

Pioneering issue on the concept of disintegration and the new Millennium. Fin de siecle broodings on breakdown, desperation and fracture. Articles explore new technologies in the arts as well as specific regions, Asia and indigenous Australia. Reviews

In this issue

Age and Consent: Ella Dreyfus

Howard Arkley

Obituary for the artist Howard Arkley who died in Melbourne on July 22 1999. Outlines his career in terms of the artistic highlights and short personal biography.

Decrepitude in Venice

Report about the 48th Venice Biennale 1999. Discusses works by various artists as the Millennium approaches: Sergei Bugarev, Thomas Hirschorn, Jean-Pierre Bertrand, Federica Thiene, Stephanie Mantovani, Dieter Roth and Louise Bourgeois. Focus on disintegration in the city of Venice.

The Future Breed: Creatures and Mad Science

Explores the links between film and computer generated games which emulate life. With the creation of artificial intelligence on the computer, complex questions of the nature of human behaviour are raised. Science fiction confronts issues of intelligence and sentience.

Who's Afraid of the Prosthetic?

Explores relationships between human participants and the machine. Describes two projects Fuzzylove Dating Data Base and The Brain Project which use their location in a technological matrix as a means of exploring inter-relationships between the user and the their sources of energy and fear, Discusses formulation of information --the computer and related technologies -- as an industry.

Things Falling Apart: The Work of Ian Howard

Discusses Professor Ian Howard's visit to Beijing - his earlier frottage works from the days of the Vietnam war and the Berlin Wall as well as the large computer painted image making. Howard's work represents direct encounters with the real world combining personal and esoteric images with public and popular ones.

A Contradiction in Time: Bleak Days After Meltdown

Independent film making is experiencing an exciting resurgence in the wake of great social and cultural change. Looks specifically at films and videos from Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and Thailand screened at the 23rd Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Sorties into the City: The art of Elmer Borlongan and Emmanuel Garibay

Explores the works of two contemporary artists of the Philipines who paint the city -- Manila -- in expressionist style, depicting narratives of survival amid inhuman conditions. Borlongan as a resident and Garibay as a commuter express their views of the city in different ways.

Fashion for Civil Disturbance Bandung-Style

An interview by Damon Moon with Rifky Effendy, a curator and artist based in Bandung Indonesia. Effendy's curatorial project Wearable has been exhibited in Indonesia. The project explores some of the living conditions in Indonesia in the times leading up to the resignation of Suharto. The idea of clothing is used as a metaphor for identity --camouflage or exposure vulnerability or protection.

Bored with Polite Language: Dissidents and Reformasi

Currently in Indonesia there is a remarkable tendency to speak, write and create art works using critical, open, and sometimes vulgar language. The contemporary art scene is full of social and political intent. Describes works by Juni Wulandari, Iwan P Wijono, Toni Volunteero and Mella Jaarsma.

Marginalia: Photography of the Here, Now

Examination of the issues raised when documentary photographers represent the alienated margins of our society despite an openly dismissive and hostile critical environment. Examines the works of photographers working in Australia who use various strategies and methodologies to document the margins. Explores the difference between photojournalism and documentary.

Life and Death on Aboriginal Land with Anne Mosey

Exploration of the work of Anne Mosey who attempts with her installations and collaborations with indigenous artists to represent the tumultuous and often tragic events of life in Aboriginal communities, in particular Yuendumu, where death and grieving are ever present elements. Discusses collaboration with Dolly Nampijinpa Daniels which explore familial and cultural histories from a dual perspective.

Naming and Reclaiming: The Searching Eye of Pam Lofts

Central Australia remains at the post-colonial interface where issues such as reconciliation, cultural dislocation and otherness are daily issues. Examines the work of Pam Lofts and her relationship as a white artist working in such an environment. Explores the distinctions between the European concept of landscape and the indigenous focus on country.

Taking Control of the Grog: Yuendumu

Mosey who acted as consultant for a video project by Pat Fiske, Valerie Napaljarri Martin and Tom Kantor which documented the damaging impact of alcohol on indigenous communities tells of the making of this video. It documents the history of the Yuendumu Women's Night Patrol from 1991.

Traumatising States: Film Reflects Dysfunction

How dysfunction, abuse, drugs, gambling, war, suicide etc are depicted through the moving image. Argues that artists are able to tease out psychic and emotional states and present them in ways which are not spectacularised as entertainment for a consumerist culture. Examines particular examples to support his argument. Refer to artists list.

The Story of Wrap me up in Paperbark

The author ( co-writer, editor and associate producer) discusses with Des Kootji Raymond (director) the production of a controversial television documentary ÒWrap me up in PaperbarkÓ. The documentary is about indigenous peoples right to reclaim the remains of their elders who were forcibly removed from their homelands as children. Discusses the repatriation of remains of Aboriginal people from museums.

TV Docos and Realpolitik

The author Des Kootji Raymond as the director discusses with Jeffrey Bruer, co-writer, editor and associate producer, the production of a controversial television documentary ÒWrap me up in PaperbarkÓ. The documentary is about indigenous peoples right to reclaim the remains of their elders who were forcibly removed from their homelands as children. Discusses the repatriation of remains of Aboriginal people from museums.

Living out the Abject/Subject

Larry Clark is a well known American photographer and film maker. The Experimental Art Foundation mounted an exhibiton of photographs from the 1960s through to the 1980s as well as a series from the film Kids. Clark's trademark is gritty realism and under age sexuality. Discussion of the boundaries of eroticism and pornography.

Laughing and Killing: The Guilty Pleasures of Anime

Anime (Japanese animation) is increasingly violent and yet the Japanese level of violence is much lower than in America. Viewed as an escapist form of entertainment with female characters idealised and existing in a male fantasy land runs counter to the Wests view of feminism. This form of popular culture is a useful vehicle to examine the country's psyche.

Reconstructing Identity in Post-Apartheid South Africa

Visual arts in South Africa since the 1970s have played an important role in the struggle for freedom. They have chronicled the country's history of political oppression, chaos and transformation. Artworks today investigate a highly individuated sense of the political self.

Disqualified Knowledges: Insight into Disturbance at Splash

Explores the positioning of artworks made by people with a mental disability looking specifically at the arts access program --Splash Art Studio. The studio encourages the voice of the participants each attempting to articulate their own knowledge. The studio operates between the dominant voices of the psychiatric and art institutions making possible a space for people to develop their own ways of working.

Empire: Michael Riley and Dreams of Return: Michael Buckley

Empire by Michael Riley produced by ABC Indigenous Unit

video 30 mins

Dreams of Return director Michael Buckley producer Julie Shiels

CD-Rom Mac/PC

The Silence: Gilles Peres and Roaring Days: Matthew Sleeth

The Silence by Gilles Peress

Scalo Publishers, 1995 RRP$54

Roaring Days by Matthew Sleeth introduction by Michael Thomas

Published by M33, 1998

Photo Files ed Blair French

edited by Blair French

Sydney: Power Publications and Australian Centre for Photography, 1999

paperback, 315pp b&w illustrations

Signs of Life

Melbourne International Biennial 1999

Telecom Building Russell St and other venues in Melbourne

11 May - 27 June

James Gleeson

A selection of work from 1978-1998

Pinacotheca, Melbourne

2 - 26 June 1999

Red Contemporary Art Events

National Gallery of Victoria

28 May - 30 June 1999

Richard Larter

An exhibition to celebrate his 70th birthday

Watters Gallery and Legge Gallery

May 1999

Transit Lounge

Keith Armstrong

Metro Arts, Brisbane

26 May - 19 June 1999

Respirare: Sebastion Di Mauro

Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane

June 3 - 26

piVot

1 July - 8 August 1999

Nexus Gallery, Adelaide

curated by Elizabeth Fotiadis

Ian Chandler

Greenaway Gallery

28 April - 23 May 1999

Jam Factory Biennial 1999

JamFactory, Adelaide

17 July - 29 August 1999

Cache: An Exhibition of Work by Artists from the Letitia Street Studios

11 June - 4 July 1999

CAST Gallery

27 Tasma Street, North Hobart

50 Reasons: Rox De Luca and Jo Darbyshire

Fremantle Arts Centre

28 May to 20 June 1999

Angela Stewart: Three Women

Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery

28 May - 27 June 1999