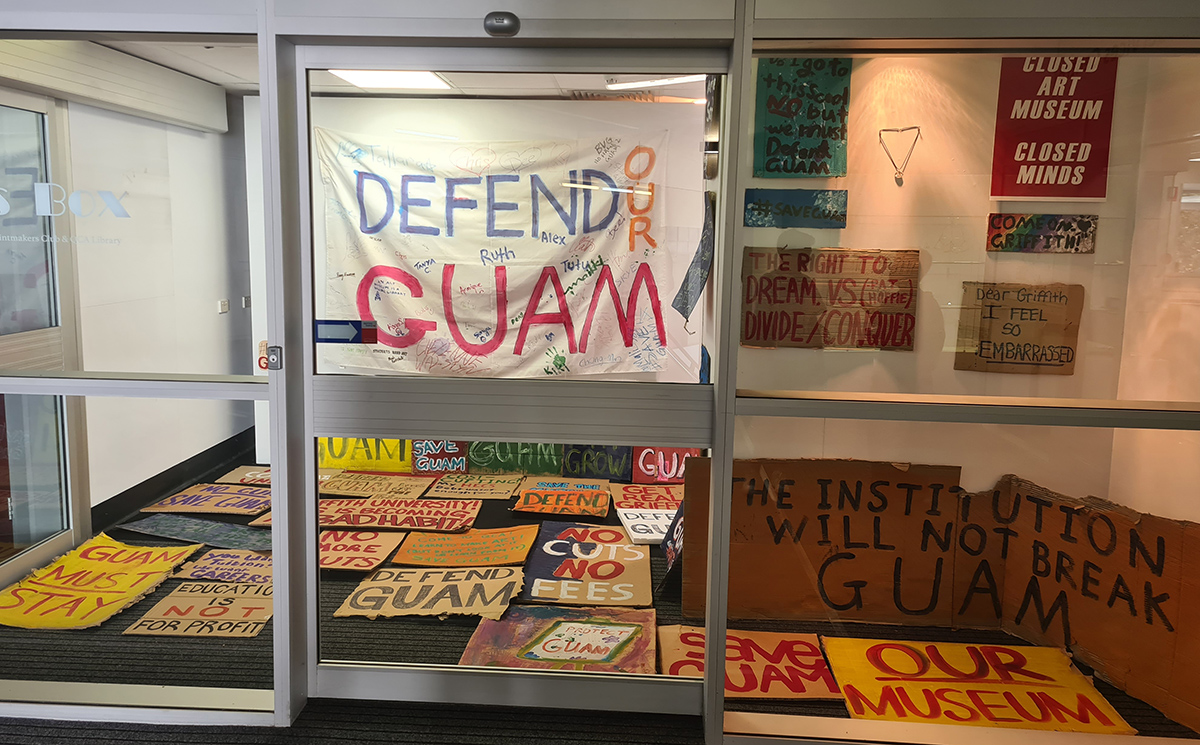

Photo: Tanya Clark.

You will know Griffith University Art Museum (GUAM) if you’ve visited or lived in Brisbane anytime since the early 1990s. It’s a beautifully appointed gallery space with a reputation for high quality and thought-provoking exhibitions and scholarship, set near the river on the South Bank Campus and the southern tip of the city’s art and cultural precinct. It’s also prime real estate and a well-proven training ground for many of the country’s leading artists and curators: a jewel in the managerial—I mean magisterial —crown of Queensland College of Art and Design (QCAD).

If Griffith was hoping for a smokescreen when it announced that it is undergoing a confidential consultation process with the staff of GUAM, its timing was perfect. The shock news of the much-loved gallery’s potential closure comes in a week of high agitation in the Australian art world: media channels have been fixated on the National Gallery of Australia’s $AU6.67 million spend on Jordan Wolfson’s robotic Body Sculpture, and Mike Parr’s dismissal from Anna Schwartz Gallery’s stable for his performance piece referencing the Israel-Gaza conflict.

Griffith University’s management argues that, due to the need for more teaching space to accommodate its growing Film School, closing the University gallery is under consideration. The local art community is perplexed and angry by this sudden threat. The consultation process is due to conclude on 15 December, allowing a brief two-week window for public feedback. With a sense of urgency, the art community has hastened to respond.

Artist and QCAD alumnus Tony Albert called it ‘completely unacceptable’.[1] A petition to save the gallery amassed over two thousand signatures within a week, and a public protest was held on 13 December at the Grey Street entrance to GUAM. Capturing the sentiment, artist and Griffith academic Susan Ostling wrote:

GUAM has become a centre for serious art viewing, thinking and discussion. Its exhibition program is of a high calibre and its contribution to an art school environment is irreplicable. To consider repurposing GUAM is to fail to see the intellectual and creative role it plays within the Queensland College of Art and Griffith University.[2]

QCAD alumni include the internationally acclaimed artists Gordon Bennett, Tracey Moffatt and Michael Zavros. Griffith University’s official succinct statement sums up management’s understanding of the gallery’s function: ‘GUAM generally displays external collections.’[3] This falls well short of conveying GUAM’s multifaceted role. The University gallery has been active in preserving the history of Griffith’s alumni and our national art community and providing opportunities for young and emerging artists, both local and international. For example, Archie Moore—the Australian representative at the next Venice Biennale—realised one of his most ambitious projects, Archie Moore: 1970-2018, at GUAM in 2018. Retrospective exhibitions have honoured the work of some of the country’s most prominent artists, including Jenny Watson, Davida Allen, Christian Thompson and Ben Quilty. In house, co-curated and touring shows have shared the work of Juan Davila, Gonkar Gyatso and William Kentridge with Queensland audiences.

Other significant outputs (to use university terminology) are publications that make invaluable contributions to Australian art history. With Hand & Heart: Art Pottery in Queensland 1900-1950 (2018) won the AAANZ Best University Museum catalogue prize and Gordon Bennett: Selected Writings (2021), published by GUAM and Power Publications, was awarded Best Book by the Annual Museums and Galleries Association. Originally co-published with documenta 15, the Richard Bell Reader was re-released in 2023 in collaboration with TATE Modern. These are just some examples illuminating the global reach of GUAM and its relationships with leading art institutions worldwide, as well as its regional art history credentials.

It's difficult to underestimate the value of the gallery. Nonetheless, Griffith University betrays apparent ignorance of the gallery’s depth of research and the cultural value its national reputation and its specialist team embodies. While citing financial losses in its decision making, it’s hard to overstate or fully imagine the negative impact of such a sacrifice.[4] When an art school closes its art gallery, it sends a clear message from the university management to their art students and the cultural sector more broadly: visual art isn’t a priority.

This is particularly devastating for Brisbane. While inner-city cosmopolites of Sydney and Melbourne boast of their respective city’s art world capital, Queensland has long endured a reputation as a cultural backwater, described by then-Brisbane resident, art historian and critic Rex Butler as a ‘double displacement’. This stigma partly owes to the legacy of the culturally repressive Joh Bjelke-Petersen premiership between 1968–1987. In the aftermath, the arts helped revitalise Queensland. The establishment of the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) in 1993 and the opening of Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art made Brisbane a global art centre which celebrated its locality.

But an art community can’t sustain itself on big ticket events alone. GUAM provides a tether between this international showcase and the local community through carefully considered programming which responds to global art currents, and fosters relationships between international and local artists as well as audiences and institutions. For example, the Indonesian art collective Taring Padi (who featured at documenta 15 in 2022) were scheduled to participate in a residency and set of public programs in collaboration with Brisbane’s Indigenous collective proppaNOW in 2024.

Such initiatives have bolstered ‘the student experience’ (so important to academic ratings) at the art school. As Kim Marston, a current student at QCAD explained on signing the petition:

Learning from the works exhibited has promoted national and global citizenship, broadening my world view through otherwise unseen yet necessary concepts voiced and visualised through its [GUAM’s] meticulously curated exhibitions.[5]

The future of these projects is now uncertain. A statement displayed on the gallery’s website says that artists in GUAM’s 2024 program will be updated regarding the future of the gallery, and ‘appropriate action taken with respect to their contracts.’[6]

Attempting to quell fears about the future of Griffith’s art collection (one of the largest in Queensland), a university representative told ArtsHub ‘The new Griffith CBD campus, which is expected to open within the next few years, will provide a wonderful opportunity to display the art collection and continue our engagement activities.’[7] But what does this amount to without the structure of the gallery, dedicated curators, public programs, and publications, plus the careful cataloguing, conservation, and archiving processes the gallery facilitates? Moreover, the credibility, criticality and cachet that artists and the art world bring in cultural capital via GUAM is far from a peripheral add-on. Without the structure of the gallery—and the genuine support of the University—the collection seems destined to become window dressing for thoroughfares and foyers to advertise the cultural currency of the institution, which will have been cannibalised by default.

Though it’s a brutal (and symbolically loaded) move on the University’s part, the proposed closure isn’t surprising considering the recent history of QCAD and the now not-so-new neoliberal turn in higher education across the country, especially given the covering of darkness that Covid-19 provided. The threatened closure is another example of what is lost when universities give up on art and culture, but this event is just one casualty of many. In 2020, Griffith University cut over 100 jobs and axed the Bachelor of Photography degree. Evidencing a trend particularly among regional universities, The University of Newcastle (NGA Director Nick Mitzevich’s alma mater) cut its undergraduate Fine Art programs all together by 2020.

Reflecting on the current crisis, artist and academic Russell Craig explained that,

Griffith made a firm commitment to uphold the artistic integrity of the College’s formidable reputation. Griffith had already carved a great artistic pedagogy through Griffith artworks and the brilliant professional workshops and art collection that Dr Margriet Bonnin and her team had carved in the 1980s. Griffith University Art [Museum] is a powerhouse [on] Queensland’s art map with a huge history and reputation that was born from the very best of this state’s leading art institutions...[8]

QCAD had an established history and reputation before being acquired by Griffith University in the 1990s. In fact, it’s the oldest art institution in Australia. Though founded in 1881, its origins can be traced to the 1840s.[9]

It's worth noting that QCAD was known as Queensland College of Art until some indeterminate time in 2023—a rebrand that appeared overnight. (While QCAD is all over the University website, signage around the campus lags.) The late art historian Bernard Smith, a card-carrying Marxist, warned of the need to protect discipline specificity. Many others in the arts have agreed, but it appears to be a losing battle. Today, neoliberal managerialism in higher education is often literalised in the departmental shifts and rebrands that softly signal the dissolve of discipline-specific degree-structures and the repurposing or wholesale destruction of facilities. Across the humanities study areas such as English Literature, Fine Art or Art History, which previously occupied departments that name-checked them in faculty titles, have been absorbed into departmental banners like Culture and Communications or Creative Industries, the latter led in Australia by Queensland University of Technology, which promotes itself as ‘a university for the real world’.

What is the real world in 2023? Today, (most) adults love Disney and Marvel films.[10] The pastimes that occupy us into adulthood are increasingly driven by fandoms and prosumerism, with the film and culture industries currently dominated by children’s media marketed to consumers of all ages.[11] GUAM’s downfall may be directly tied to such perpetual kidulthood. The international success of children’s television program Bluey (2018-), an animation about an anthropomorphic blue heeler dog created by Griffith University alumni, has raised the profile of Griffith’s Film School. Its growing enrolment numbers are attributed to Bluey’s fame, arguably inadvertently sabotaging GUAM’s future.[12]

Kelly Gellatly highlights that the Film School would only gain 250 square metres by repurposing GUAM, an insignificant portion of a university that owns five campuses in South East Queensland.[13]

Regardless of the reasoning, if the Griffith University Art Museum closure goes ahead, it will be a substantial blow to art education in the state, and another example of universities eroding, rather than scaffolding Australian cultural life. It would also indicate a lack of investment in the next generation of artists, curators, arts leaders and art critics.

Public feedback can be emailed to the university on guamfeedback@griffith.edu.au before COB Friday 15 December. You can also sign the petition.

Footnotes

- ^ Tony Albert quoted in Liz Hobday, “Jobs on the line as uni considers gallery closure”, The Canberra Times, 6 December 2023

- ^ Change.org, “Defend Griffith University Art Museum (GUAM) preserve our artistic and cultural legacy”, accessed 10 November 2023

- ^ undefined

- ^ Griffiths University, “Proposed Changes..."

- ^ Change.org, “Defend Griffith University Art Museum…”

- ^ Griffith University, “Proposed Changes…”,

- ^ See Gina Fairley, “Potential Griffith University Art Museum closure”, ArtsHub, 5 December 2023

- ^ Fairley, 2023.

- ^ Griffith University Library blog, “Queensland College of Art Celebrates 140 Years of Teaching” 6 April 2021.

- ^ Richard Newby, “What happens when fandom doesn’t grow up?” The Hollywood Reporter, 1 September 2016

- ^ Eliana Dockterman, “Adults are Spending Big on Toys and Stuffed Animals—for themselves”, TIME, 17 November 2022

- ^ Phil Brown, “Did Bluey just accidentally kill off a leading Brisbane art museum?” In Queensland, 7 December 2023.

- ^ Kelly Gellatly, “Why University Art Museums play a vital role”, ArtsHub, 11 December 2023