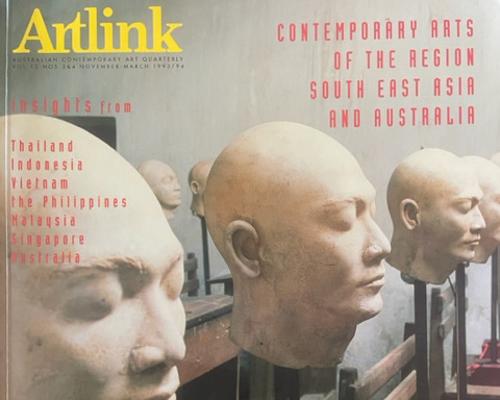

Why is the island-nation of over 280 million people to our immediate north largely invisible in current Australian art discourse today, given the strong groundwork of the 1990s? How can we render a sense of Indonesia’s contemporary art while conveying the cultural and historical links between our two nations? These questions are too big for Artlink, but we can push against them by showing the vibrant art practices occurring across the archipelago, much of it written in Indonesia. We can only do this thanks to the generosity of leading Indonesian art specialists Wulan Dirgantoro, Elly Kent and Aaron Seeto, our editorial advisors on this issue.

Indonesian art’s low visibility in Australia is partly explained by numbers. Despite our two countries’ proximity, 2021 census data reveals that there are just under 90 thousand Indonesian-born Australians, or .3 per cent of the entire population. By comparison, England-born Australians comprise 3.8 per cent and India-born 2.8 per cent of the population. Another reason might be that nationality takes a back seat in the globalisation of contemporary art, despite the rise in identity politics. As Seeto put it over a decade ago,

The changing context now is for contemporary art itself: not a narrowing of its referents, but a larger global appreciation for the kinds of influences and trajectories that Australian artists have been part of for some time. In this context, our broader cultural discussions should be geared towards participating in this broader cultural context, inside and outside of Asia.[1]

Seeto was picking up on what was already a long-running intercultural project, canonised in the Asia-Pacific Triennials (APT) launched by Queensland Art Gallery (now QAGOMA) in 1993—ten versions deep in 2021. Is it possible our cultural interests are more internalised than thirty years ago? As one contributing writer told me, ‘Oh APT history, everyone knows that…’ But our “everyone” is changing. Seeto’s reflections in 2011 still hold true:

… our [Australian] history of colonisation and its modernity is intimately linked with experiences of migration which produces a particular anxiety of “how do we belong here, how do we belong elsewhere”—not a phenomenon of being contemporary but a product of our history.[2]

Also contributing to the relative invisibility of Indonesian art in Australia is the absence of Indonesian art history, let alone its postcolonial history, in our local consciousness. We might have expected documenta fifteen in 2022 to have changed that. Staged by the Indonesian collective ruangrupa, it put Indonesian art on the global artworld map, but it was quickly usurped by Eurocentric sensibilities sparked by German shame over its genocidal past and amplified by European media trigger‑ready to censure. The main accused was People’s Justice (2002), Taring Padi’s banner first exhibited in the Adelaide Fringe Festival in 2002. There and then, indifference to its iconography prevailed, despite the banner’s visual coda representing the authoritarian regimes of twentieth century Indonesia. Less publicised in the documenta fifteen coverage were over 100 additional works by Taring Padi, made over 22 years and comprising countless visual history lessons for the people: post-colonial Independence from Dutch rule in 1947–49 led by First President Sukarno; Suharto’s 1965–66 bloody coup against Sukarno, and 32 years of his New Order regime which ended violently in May 1998, followed by the contemporary ‘Era Reformasi’.[3] As the editors of Living Art: Indonesian artists engage politics, society and history put it

Indonesia’s artists are its intellectuals and philosophers of the visual. […] They also recognise that artists are acutely observant of the political as well as the social aspects of their society, and that they should not remain silent about abuses of power.[4]

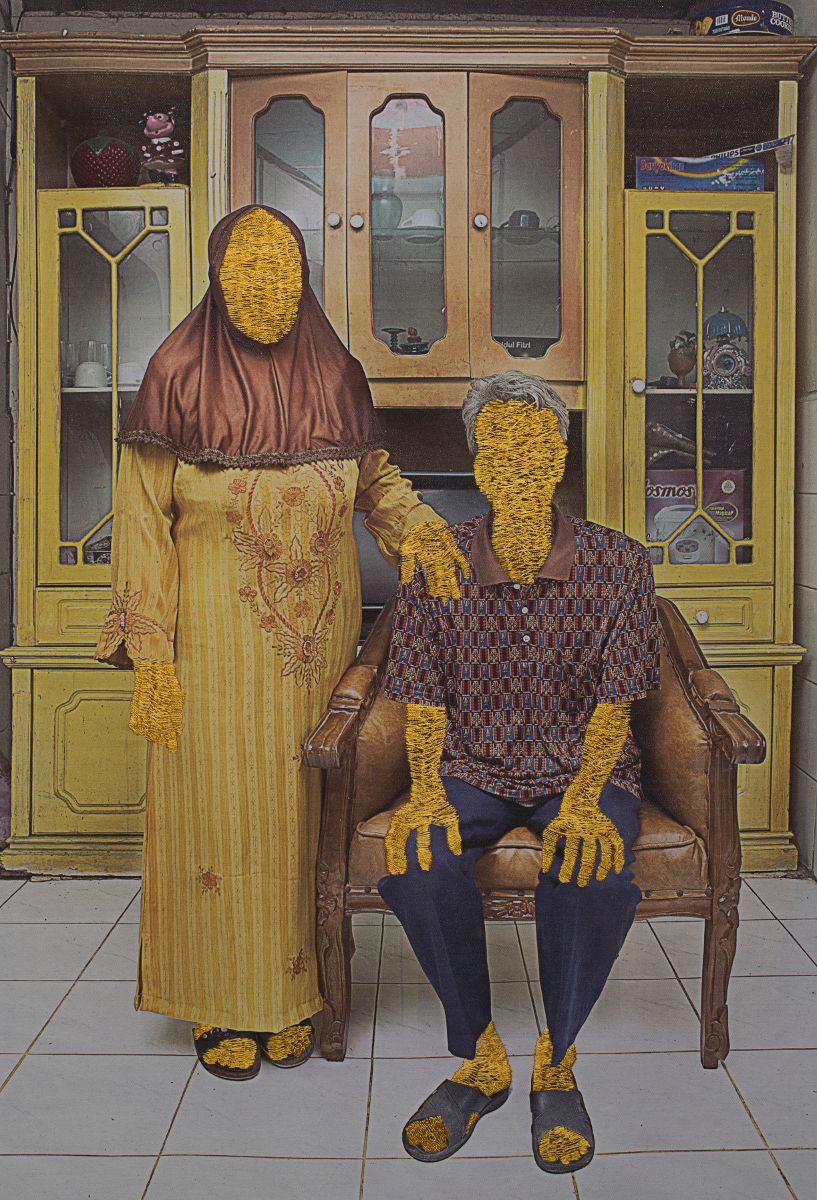

Likewise, the artists and writers in this issue make clear that governing forces have and continue to play a heavy hand in Indonesian people’s lives: the week we sent out writer’s contracts, Indonesia announced a new criminal code (KUHP), raising concern among international human rights groups and freedom of speech advocates.[5] Being so closely aligned to lived experience, Indonesia’s art generates an activist legacy that has a comparatively low silhouette in Australia. Modernity, identity, tradition, struggle, humanity, justice, transition, cosmopolitanism, globalism, action, “Javacentrism”, feminism…all these and more perforate Indonesian art, historically and to this moment.

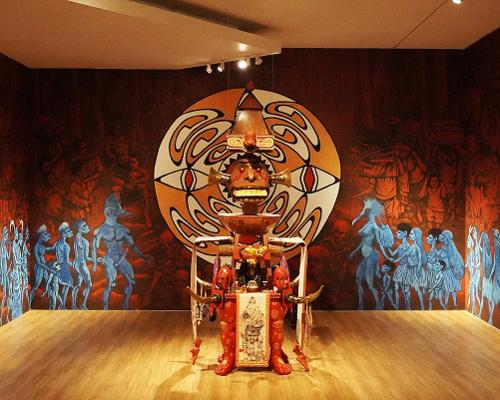

This is apparent in the three sub-themes in this issue which loosely reflect the editorial team’s expertise: collective, socially engaged art practices, Indonesian women’s and feminist art histories, and some aspects of its art traditions and cultural architecture. Our cover image, part of the performative installation Koreri Projection by the emerging West Papuan collective Udeido, combines all these hybrid elements: a giant ceremonial mask, part‑armature, part‑costume that challenges gender and cultural stereotypes as it activates the metaphorical streets.

Collectivity and social action

As Elly Kent writes here and expands on in her essay in this issue,

It’s one thing to say that collectivity in Indonesia aims to bring artistic practices into closer contact with the “reality in society”, but what are those social realities? … Acknowledging that there are few traditional societies that didn’t favour collective action, why does collectivity dominate the art scene in Indonesia when in Australia individual artistic practice has become normative?

She also notes that as collectives become part of “the art establishment”, they are often motivated to share and pass on their knowledge to a new generation of collectives—often modelled on their own. Ruangrupa is an excellent example of this—over 20+ years they have become the art establishment in Jakarta, and in 2018, they formed Gudskul: Contemporary Art Collective and Ecosystem Studies, ‘… a collective working simulation study space that promotes the importance of critical and experimental dialogue through a sharing process and experience-based learning.’[6] Its activities are many and varied, but still dominated by “ruru”(short for ruangrupa) tagged ventures in communications, arts and education, and since its inception, heavily focused on “studi kolektif”. In practice, this refers to a continuous curriculum of study for collectives, now entering its sixth year, which culminated in documenta fifteen’s extravagant and contentious presentation of global and local collective art practices.

As a harvester at the recent documenta, Putra Hidayatullah reflects on these events from the context of his own locality in Banda Aceh, posing open-ended questions about the art world’s sincerity when it opens the floor to experimental collectives and then doubles down on controlling art’s imagery and its interpretation. Also on the topic of art’s appreciation, Caitlin Hughes writes about critical writing and publishing collectives and reading groups in Makassar, East Indonesia, as a means of recentring narrative—and centring the community in this storytelling.

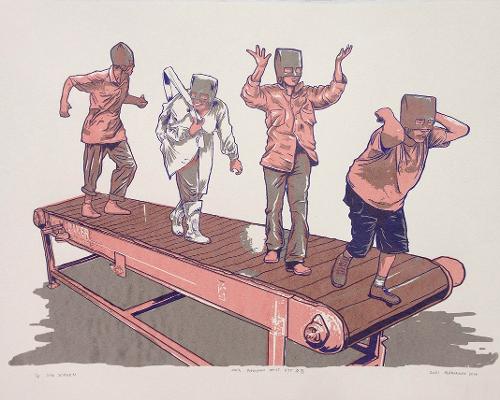

Between Sukma Smita in Yogyakarta and Malcolm Smith in Sydney a discussion unfurls on what ingredients have made Krack Studio in Jogja a success ten years on. For this printmaking collective, the ubiquitous ‘ekosistem’ paradigm, (rather than an identity politics model) has been most productive, and Krack’s openness to ‘artists from everywhere’ and avoiding an overly bureaucratic approach is key to their strength.

Cultural architecture: seeing and believing Indonesian art

In 2019, the National Gallery of Australia’s Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia delivered further on the promise that founding Director James Mollison (b.1931–2020) made to collecting international art—though prior to acquisitions from Contemporary Worlds, Indonesian holdings were mostly nineteenth century textiles, religious objects and colonial photographs. A roundtable led by NGA Curator of International Art Russell Storer and Aaron Seeto, Director of Museum MACAN in Jakarta with curators in Singapore and the Netherlands gives insight into the collecting history of Indonesian art in their respective institutions, and the challenges of imagining new narratives to exhibit Indonesian art. At the other end of the art collecting line, Eliza O’Donnell writes on the art market in Indonesia and the rise of forgery of works by internationally recognised artists such as Affandi and Heri Dono.

Building cultural infrastructure, policy and exchange is occurring at different rates in different zones. Richard Horstman’s report on the localised work of the Gurat Institute in Bali, a region synonymous with tourism and hence challenging perceptions of traditional souvenir markets is one example; pioneer of Indonesian-Australian cultural exchange, Alison Carroll’s ongoing call for greater bilateral efforts to build an Australian physical presence in Yogyakarta is another. Based in Jakarta, Korean co-curator and academic Jeong Ok Jeon documents the efforts of the Indonesian cultural policy makers to deliver new technology and skills development through their regionally circulating Media Art Community Festival. Also crossing borders, disciplines and generations, Aushaf Widisto responds to the writing of Pak Jim Supangkat in his contribution to the Artlink Archive Project.

Women (up)rising

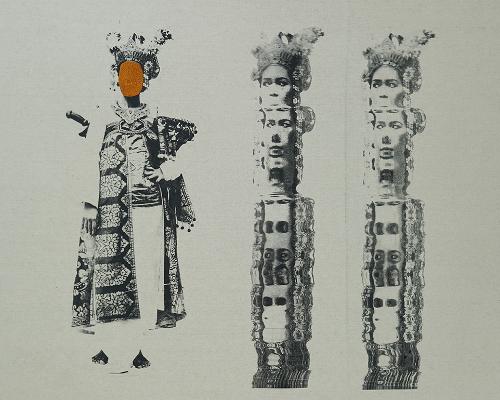

The late I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih, or ‘Murni’ is hardly representative—if that’s even possible—of Balinese women artists. However, her triumphant and personal paintings are better-known than her sculptures, encouraging Balinese curator Savitri Sastrawan to weave a curious narrative through Murni’s sculptural practice. Her case studies involve recent Gajah Gallery exhibitions, including Shaping Geographies: Art | Woman | Southeast Asia co-curated by Michelle Antoinette and Wulan Dirgantoro, whose feminist scholarship on gender, memory and trauma in Indonesian modern and contemporary art and nation informs other essays in this issue. Jennifer Yang’s research on Chinese-Indonesian women artists and art historians pushes against a tide of intersectional invisibility, sexual oppression and ‘a violent form of amnesia’, which, like Murni’s work, discloses the unthinkable.

Hong Kong based Liu Mankun’s close exploration of Natasha Tontey’s queer/indigenous moving image work located in Minahasa, northern Sulawesi touches on the similar performative currents as described in the collaborative work—and writing—of Melbourne-based Balinese moving image artist Leyla Stevens and extreme metal vocalist Karina Utomo. Also living the diaspora but bound to place through incandescent memory of Indonesia’s intergenerational traumas, artist and scholar Tintin Wulia (who divides her time between Bali, Sweden and Brisbane), evokes all shades of Indonesia’s history and geography in her spare and unforgiving prose.

Bridging futures

Looking back from the other direction and given the lack of cultural investment in Indonesia, what do Indonesians know of Australia’s history of colonisation from 1788, or the centuries of Makassan and Aboriginal exchange along the continent’s northern coastline? Australia might speak of building bridges with Asia, but the world sees it burning boats. More optimistically, artists and writers from both sides of the Timor and Arafura Seas appear to be genuinely interested in crafting and sharing the raft. The professional standing of our editors at key institutions in Australia and Indonesia, and their ongoing scholarship within a growing field of peers globally, is further cause for confidence.

A final note on language. Most writers in our Indonesia Focus are bilingual or multilingual, but we have commissioned them to write in English.[7] Both Elly and Wulan are experienced translators of Bahasa Indonesia, and as academics, educators and curators they navigate the perils of International Art English and writing on art for global readers—as does Aaron in his directorial role. My approach as in-house editor has been to preserve the original voice and syntax of the authors as much as possible, and I owe thanks to all the contributors for their patience and attention to detail. After reading Tiffany Tsao’s passages on the subtle art of translation in her review of Indonesian novelist Eka Kurniawan’s Beauty is a wound, I returned to Savitri Sastrawan’s essay and reinstated Murni’s ‘privates.’[8] We cannot be too careful with words.

Footnotes

- ^ Aaron Seeto, A landscape with or without you, Artlink, 33:1, (March 2013), 56

- ^ Aaron Seeto, Transcultural Radical, Artlink, 31;1, (March 2011), 28

- ^ Tim Lindsey, “Post-reformasi Indonesia: the age of uncertainty”, Indonesia at Melbourne, 4 May 2018, https://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/post-reformasi-indonesia-the-age-of-uncertainty/

- ^ Elly Kent, Virginia Hooker and Caroline Turner, Living Art: Indonesian artists engage politics, society and history, (Canberra: ANU Press, 2023), 81

- ^ See Ratu Durotun Nafisah, New criminal code exposes deep problems in Indonesian legal education, Indonesia at Melbourne, 31 January 2023, https://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/new-criminal-code-exposes-deep-problems-in-indonesian-legal-education

- ^ Gudskul also has its own website, which further explains the collective, not-for-profit funding model, in which grants and donations given to participating collectives are pooled and redistributed according to need. See https://gudskul.art/en/about/. According to their websites all three founding collectives, and Gudskul, also conduct commercial businesses in arts management, design and communications, education and art handling. See https://ruangrupa.id/en/gudskul/, accessed 6 February 2023

- ^ Previous issues of Artlink including This Asian Century (2013) and Korea (2015) were commissioned in the writer’s first language. The 2011 issue of Artlink Indigenous was translated into Chinese

- ^ Tiffany Tsao, “In Suspicion of Beauty: On Eka Kurniawan”, Sydney Review of Books, 18 March 2016, https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/review/in-suspicion-of-beauty-on-eka-kurniawan/