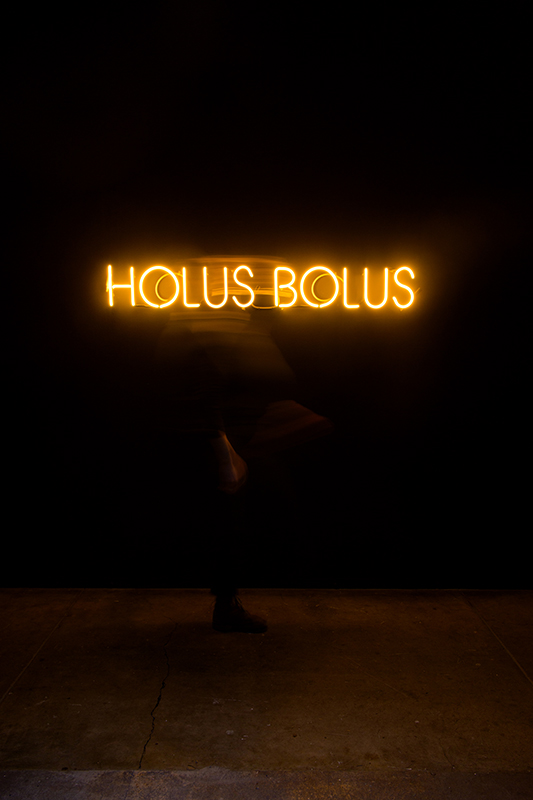

The words ‘holus bolus’ are written in gold neon on the gallery wall. This is something Tina Havelock Stevens heard her mother say before she died, meaning ‘all at once’. It captures, for the artist, the sense of living in the ‘extreme present’ of early 2020 when the work was made: grief combined with a summer of catastrophic bushfires and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the darkened gallery of the Substation, Holus Bolus (2020) glows with the witches’ hurley burley, a tense prescience heightened by the context in which I am encountering it: on the eve of 6 August and Melbourne’s lockdown six, which is being announced as I arrive. It seems that this lockdown is not like the others, in the sense that there is no relentless drive to zero, no on/off staccato, but a gathering up of all our grief and worry and reshaping it along with what our lives will be, post-pandemic. I’d been rushing around the gallery, ‘getting it done’ like housework, worried about the traffic on the West Gate Bridge. Holus Bolus is an expression of collective grief, but also a personal one, and I feel a sense of responsibility as witness, given so few people have been able to experience the exhibition in person. I decide to slow down and start again—at Thunderhead (2016).

On screen is some kind of weather formation: a semi-solid sculpture on the horizon, seen from the window of a car as you drive past across an empty, scrubby plain, framed by mountains in the distance. The music moves from tense to meditative, ominous, otherworldly and back again. The car is moving but you aren’t getting anywhere, remaining in the same relation to the formation, as you would a rainbow. This is not an optical illusion, but an extreme thunderstorm or ‘super cell’; the sides of the ‘sculpture’ are sheets of rain held in orbit by a powerful, rotating updraft that may turn into a tornado. Pleasurable aesthetic input—scale, composition, colour, sound—is combined with subject matter about which all humans are primed to feel emotion: the weather, and its relation and distance to us, the promise of its impact on our lives.

This evokes the trope of the sublime—in particular, its Australian settler-invader incarnation, in which the spiritual possibilities of communion with nature are laced with an anxious sense of alienation and displacement. (The cloud looks less like Turner or Twister to me and more like Picnic at Hanging Rock.) The film wasn’t shot in Australia, but in Texas. Havelock Stevens later improvised the score with longtime collaborator Liberty Kerr, and the music draws out a Freudian ‘unhomeliness’ both familiar and strange. The music doesn’t settle, moving through different emotional repertoires. You’re traveling in a physical sense at the same time, but remain anchored in relation to the super cell, comfortably suspended in a state of perpetual non-arrival.

Well, not ‘comfortable’ exactly. There’s an intensity of emotional tenor, an ominous glower that seems to reflect postcolonial unease. For an artist of Havelock Stevens’ generation, this embraces not only the legacy of dispossession, but the threat and reality of climate change. The exhibition is not ‘about’ climate change—nor the pandemic—in any direct sense that I can detect. But Holus Bolus unites these incidentally by the context in which it was made and thus colours my experience. Both climate change and the pandemic are manifestations of an intensely interdependent and therefore fragile global modernity, in which a problem at a local level (a fire, a novel virus) quickly engulfs or infects the system as a whole.

Perhaps this thought solidified later when I looked at Ghost Class (2015), which depicts Havelock Stevens drumming, as darkness falls, from the carcass of a grounded plane. She’s in what is known as a boneyard, where planes are put to pasture. Carcass, pasture: why does Ghost Class remind me of a sculpture I know well, a life-size wax depiction of the dead body of a horse? The ‘bones’, remnants of seating and other structural refuse, are visible from the insides of the passenger jet where she performs. Planes and horses represent key technologies enabling the transport of humans, timestamps in our cultural evolution. Seeing this big beast grounded stimulates those pandemic-themed emotional responses; for me, this is less to do with cancelled holidays than about waiting to find out whether this (pandemic) is a temporary pause on our march of progress, or the opportunity to take a different route. I’m not even sure what I want to be the answer.

Ghost Class is one of three works that revolve around Havelock Stevens ‘drumming places’, visiting sites that are charged or loaded in some way, and recording a spontaneous composition—one that taps into the frequency of that place and time. In Giant Rock (2017) she performs before a freestanding boulder in the Mojave Desert, a site that’s hosted the expression of conflicting belief systems, from Native Americans of the Joshua Tree region to UFO enthusiasts.

Works like Giant Rock and Ghost Class sit at the heart of Havelock Stevens’ practice in the sense that they unite her craft as a filmmaker and musician for the purposes of creating… something else, something greater than the sum of those parts. The opportunity, perhaps, to occupy a particular moment in time and space, that’s consonant with the history and politics of ‘occupation’, but nonetheless determined to privilege the human propensity for peace and acceptance that persists beneath all the social and historical change.

To this end, The Rapids (2019) takes as its premise the spontaneous drumming practice I have just described. The charged space this time is around the Aguang River in Baler, the Philippines, location for the filming of Apocalypse Now; and The Rapids loosely follows the trajectory of that film, from Charlie’s Point where Havelock Stevens performs, up-river and into the jungle, where a second performance is watched (unscripted) by a Brahman cow.

Both Apocalypse Now and its source text, Heart of Darkness, operate within the bounds of the imperial narrative, in the sense that the reader or viewer is positioned to see the world through the eyes of the European or American invader, and the setting in both cases (the African Congo, Vietnam) act as backdrop to his emotional and psychological journey. But the river-as-narrative-arc that structures those imperial adventures is disrupted in Havelock Stevens’ film by intense focus on the visceral qualities of water. Historical footage of people swimming or fishing is interleaved with images of local waterways, sitting in stillness, lapping, trickling, flowing in different directions and at different speeds. This is presented across two screens, which work together to create mesmerising patterns in conjunction with a cyclic drumming soundtrack that rises and falls, speeding you forwards then declining; exhilarating like a rapid pulse, exuding a quality that can only be called ‘bad-assery’. And she looks super cool cutting sick like that on the edges of the water—actually, in the water, and the thickets of the jungle; out of place, unquestionably a visitor, as the cow looks on askance.

By now I’m keen for a close-up of the artist who figures in medium or longshot in this survey exhibition. Or not at all, in the case of one of the smaller video installations, Come Together, Right Now (2006/2018), which is more properly observational than the others. It depicts a group of strangers mourning together at Strawberry Fields on what would have been Lennon’s sixty-sixth birthday. Finally, in Let’s Groove (2017), my favourite, she turns the camera on herself in portrait range, face and shoulders bare.

The background is a blur of soft orange. She’s not looking at the camera but is acutely cued to its gaze, trying to manage (it seems to me) a feeling of exposure and discomfort. Her body is moving in a way that isn’t immediately interpretable; after a moment it’s clear that she is drumming, the sticks moving in and out of the foreground but the shot trained squarely on her face. The invasiveness of this and the way I gobble it up invokes the ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’ of women in film. But her vulnerability complicates her status as screen ‘object’; she is performative and self-conscious all at once, both states informing and amplifying the other. Her hair hanging in her face makes her seem a little adolescent, which leads to the subject of the film. I put on headphones to hear a kindly male voice begin a drumming tutorial. A familiar pop/disco riff begins— Let’s Groove by Earth, Wind & Fire, the first piece she learned to drum as a teenager.

This is a self-portrait made before ‘a significant birthday’. Her depiction takes shape as a push-and-pull of time: between her adolescent self when drumming settled into the core of her identity and a mature woman, facing ageing. I know this feeling. The time-trap, I mean. Something I struggle with is the urge to capture significant moments, mostly to avoid the regret that might settle on me later that I wasn’t adequately present for that moment. Of course, what happens is that time traps me, instead. The trap is broken here, though, at least in part: the loungeroom performance was spontaneous, recorded only once.

It is time to go. Lockdown beckons. There are things that must be done. I take a moment to acknowledge the fact I have grown out of panic-buying toilet paper and Tim Tams and into panic-seeing art. The staff at the Substation are heartbreakingly professional and thank me for coming, even though they must be anxious in ways both generic and specific.

As I leave, I look at Holus Bolus again and it occurs to me: this represents an acute, not a chronic state. The ‘extreme present’—whether due to suffering and loss, or to the more positive, meditative state that many of us long for—is not possible permanently. The self-portrait that I loved so much was spontaneous—but captured to be looked at later. That’s how we’re put together. The difference between me as I am now and the younger version is that I forgive myself these existential incapacities. And can therefore enjoy the moments when time, in that ‘trapping’ way, breaks for a while, as it did this afternoon.