Catherine Truman has been preoccupied with intersections between art and science for over twenty years, having worked with neuroscientists, anatomists and microscopists as well as spending considerable time immersing herself in the study of historical anatomical representations and collections. In 2019, she undertook two simultaneous residencies, one in the Botanic Gardens of South Australia’s State Herbarium and the other in the Flinders Centre for Ophthalmology, Eye and Vision Research, Flinders University’s School of Medicine. Shared Reckonings emerges from this project, in an exhibition that forms part of the official program of the 2021 Adelaide Festival and which is housed across the Santos Museum of Economic Botany and the Deadhouse in the Botanic Gardens.

It is hard to imagine a more perfect context for this body of work. The nineteenth-century Museum, having survived the museological modernising impulses of the twentieth century with its collections and museum furniture intact, is now the last surviving example of its type in the world. In Truman’s hands it becomes a kind of third space in which the fields of science and art — so often thought to be irreconcilable — can find common ground. The Museum’s highly aestheticized spaces and its meticulously crafted objects remind us that in the not-too-distant past scientific museums and art galleries shared aesthetic ground, and this allows for a set of reflections that acknowledge the ways in which intuition, speculation and the poetic are intrinsic to both art and science.

Truman starts with the assumption that artists as well as scientists are researchers, and embeds herself in scientific communities to explore the ways in which their practices and her own might be seen to be analogous. Her methods are founded on open conversations with scientists in which she makes equivalencies between their equipment and laboratories and her own tools and studio, thereby creating a discursive space in which both her own activities and those of scientists are equivalent creative acts.

In entitling the exhibition Shared Reckonings Truman shifts the focus from herself as a lone creative artist to acknowledge the contribution to her own practice of the scientific communities alongside whom she has worked. Perhaps the most direct result of these relationships can be seen in the seven experimental videos that form part of the exhibition. Made in collaboration with neuroscientist, poet and videographer Ian Gibbins, the videos serve to establish visual links between Truman’s two disparate residencies. In one film, the ripples created by the slow drop of water on a nasturtium leaf invoke the teary blink of an eye. Later in the series, we see Truman’s own eye as it blinks and shifts its gaze under the forensic scrutiny of Angela Chappell’s ophthalmic camera. There is an uncomfortable intimacy to the camera’s too-close focus. The black-and-white medical imaging renders the tissue surrounding Truman’s eye with an oily silvery sheen, her iris and pupil an undifferentiated impervious black. The image of the eye is “made strange” in a manner reminiscent of early surrealist film but equally owes its uncanny qualities to the aesthetic register of medical imaging technology that increasingly reveals to us what is most intimate and also most unknown about our own bodies.

The videos run continuously in the installation in the Museum, establishing an aesthetic ground for the focal link between the two aspects of Truman’s residencies: the way light can be seen to operate on plants as well as the human eye, and how light determines the structures of both. Truman commenced work on Shared Reckonings as Eastern Australia endured the catastrophic 2020 summer bushfires and completed it over the period of isolation imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic — lending a dark register to the works.

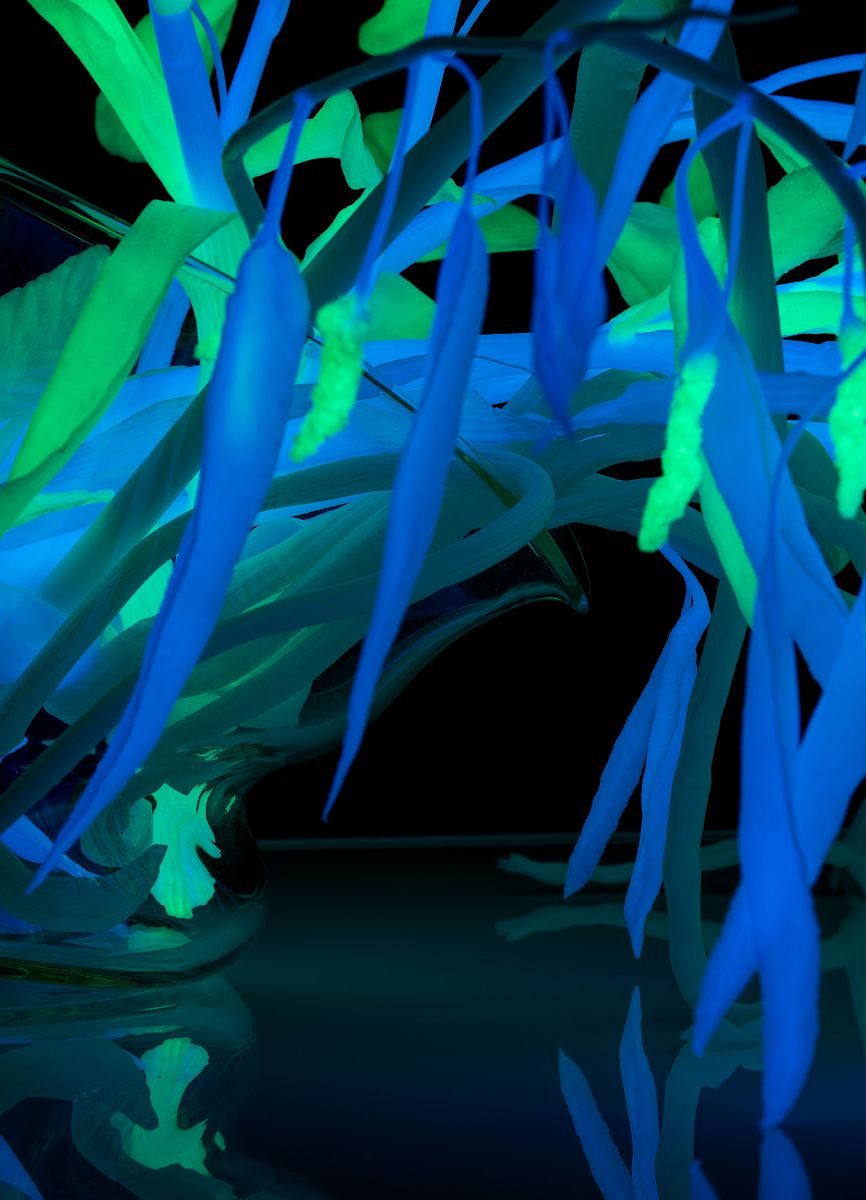

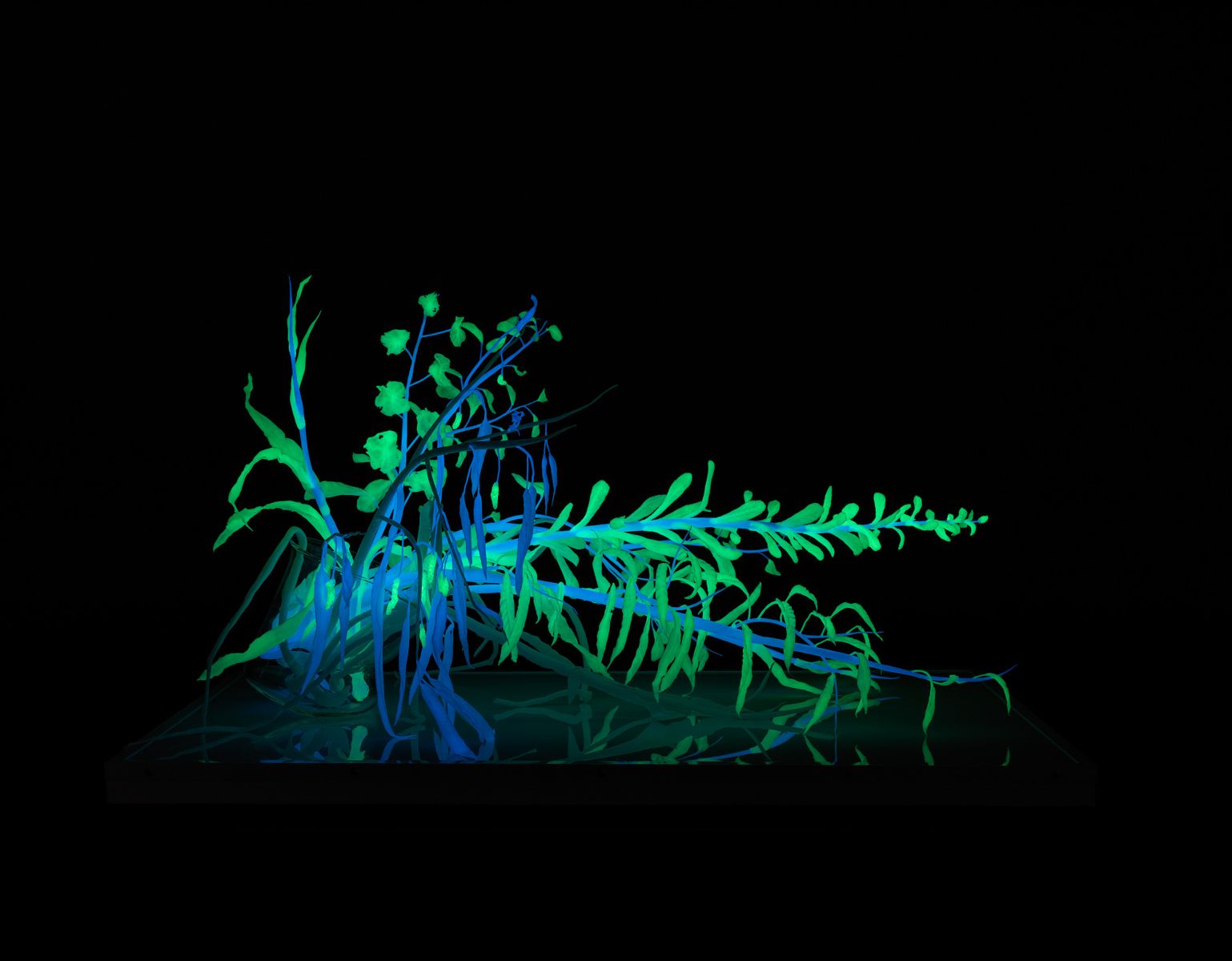

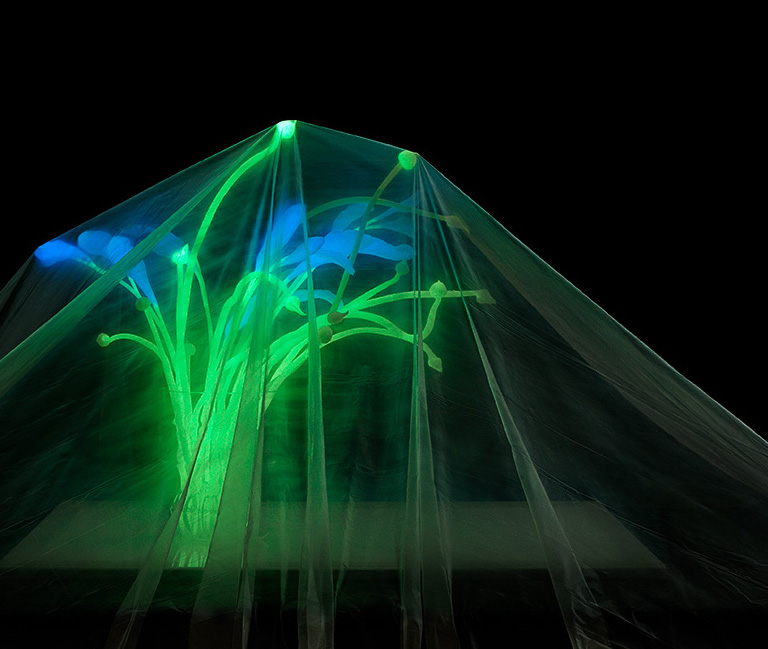

In the Museum Truman also presents a spare series of installations of imagined plant hybrids, assembled from castings of leaves impressed into white thermoplastic that has been impregnated with photoluminescent powder. In Ghost and Shared Reckonings, arrangements of her plants in beakers are something between botanical specimens and a form of uncanny bonsai, their bleached whiteness suggesting an indeterminate state — not quite alive and not yet dead. A viewer needs to spend time with them to appreciate their full resonance as they are lit alternately by the ambient lighting of the Museum itself and by timed doses of white light from the light-boxes upon which they sit. Each dose of white light feeds the photoluminescence in the plants so that for several minutes after the light-boxes switch off the plants glow a ghostly green and blue, as though remembering their previous lives as living plants through a form of mimetic photosynthesis.

Sequestered at one end of the Museum behind an arrangement of screens, the work establishes an uncomfortable conversation with the Museum’s historical collection of plant models. The artificiality of these models mirrors that of Truman’s forms, but while one speaks of a nineteenth-century confidence in the possibility for endless human exploitation of the natural world, the other speaks of the twenty-first century’s most pressing crisis: an ecological tipping point where the environment can no longer keep bending to the demands of human consumption.

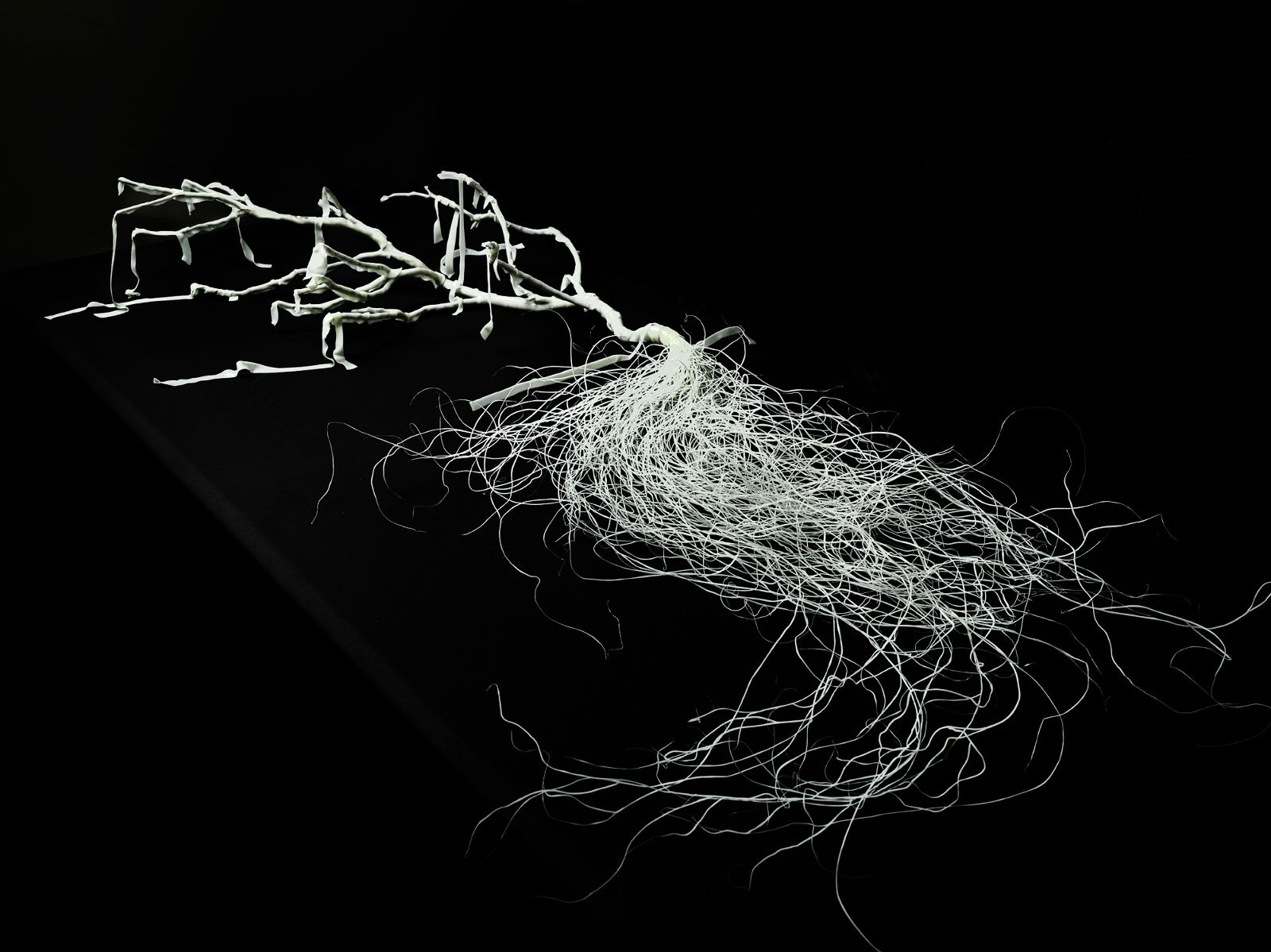

If Ghost and Shared Reckonings suggest a natural world on life support, Dark Matter and Graft — both made in direct response to the 2020 bushfires — propose a vision of the kind of natural world we can expect when the machines are turned off. Dark Matter’s arrangement of dank, dead, black thermoplastic leaves and branches droops and sprawls across the reflective surface of its black Perspex plinth-top like a floral arrangement left to die in an abandoned house. Graft is modelled on a fallen branch from a partly burned eucalyptus tree, collected after the fires. Trailing a long horsetail of roots, the work reposes in a museum vitrine, its branches held together with green thermoplastic “bandages” that echo the grafting tape used by gardeners to propagate new plants and which dangle like remnant leaves. Whether the bandages represent a healing of sorts or simply a forlorn attempt to remedy disaster is left open: we are still living inside the emergency and it is still too soon to know.

The material and formal properties of these works speak of Truman’s preoccupation with the effects of light on plants and on the human eye in a series of deft metaphorical conflations. What we read as roots in these works are also analogous to the neural and vascular networks that feed our retinas, whilst her use of photoluminescence in her plant forms both mimics photosynthesis and returns the viewer to an awareness of their own eyes as the ghostly glow of her imaginary specimens suggests the retinal afterimage we experience when we move from light to sudden darkness.

In Restless Calm the synthesis between the appearance of the structures of plants and those of the human body is even more seamlessly integrated. This work is installed in the Deadhouse, a small stone foursquare structure built in the late nineteenth century as a morgue for the Lunatic Asylum once housed in the grounds of what are now the Botanic Gardens. As its name implies, this tiny building carries with it a melancholy story of loss and dispossession. The bodies — many of them Indigenous people — accommodated in this tiny morgue were frequently subjected to dissection and medical experiments that saw their body parts sent to scientific collections in Europe and Great Britain. In more recent years, it has served as a storage building for gardeners’ tools and in Restless Calm the artist makes reference to both of these aspects of the building’s complex history.

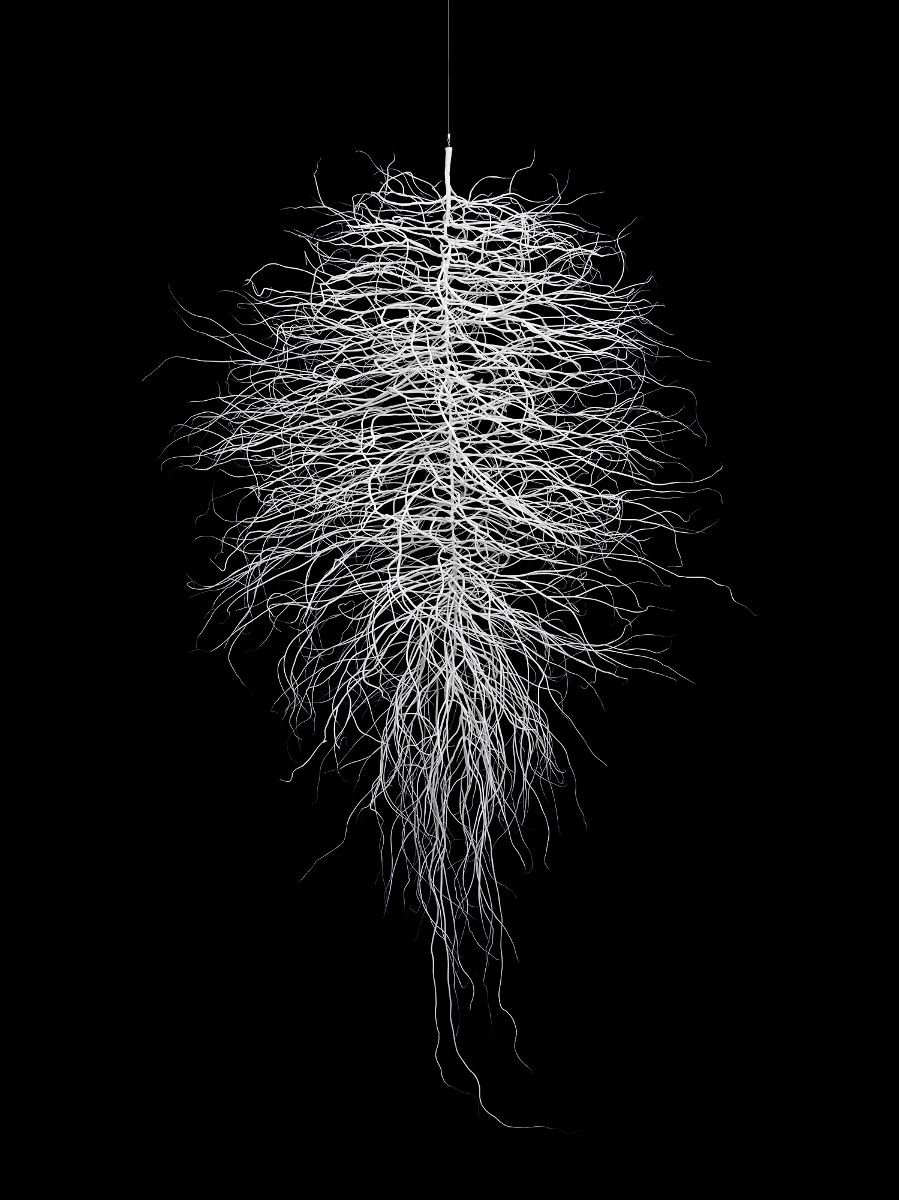

Through large windows inserted into the doors of the space, the viewer can see suspended what looks like an intricate bone-white root system almost as big as a person, slowly and ceaselessly rotating over the drain hole that forms the centre of the building’s floor. Its movement powered by solar panels, the brightly illuminated work allows us to read simultaneously the giant spread of the hidden root systems of mature trees in the surrounding garden and the intricate networks of vascular and nervous systems of the bodies that once rested in the Deadhouse and that live on in our own. If light is the source of energy that literally propels the work, it also shapes the way in which we read it. It is impossible to view the work without looking at it through our own reflection in the glass, measuring its scale against that of our own body, framed by the flourishing trees and plants of the botanical gardens behind.

Whilst both the Museum and the Deadhouse undoubtedly provide a rich semantic context for Truman’s project, they do not allow for the perfect control of ambient lighting needed for the luminescent aspects of the works to be seen to full advantage. Accordingly, a visitor’s experience of the works’ qualities might vary considerably depending on the time of day that they visit. This is particularly true of Restless Calm, which might be said to have a secret life of its own, known only to those able to attend night events in the Botanic Gardens. As darkness falls and the Gardens close, the lights that illuminate the work are switched off; powered by the stored-up energy of that day’s sunlight, the work continues to spin, glowing a bright iridescent blue in the dark. Some may consider the fact that we don’t see all the potential of the work as a shortcoming, but it is also possible to read these “uncontrollable” aspects of the installations as akin to the way in which bodies and plants behave in the world, adapting themselves to the conditions in which they find themselves, investing them with a certain unknowable quality that requires our own imaginations to complete them. We might in fact take our cue from Truman’s own words … there is making after the making … the object has gained an afterlife … and decide that to imagine the work’s secret blue revolutions in the dark may be enough.