In his public lecture for Experimenta Life Forms, The Tissue Culture and Art Project’s Oron Catts spoke of the impoverishment of the English language when it comes to words for ‘life’. Life, he suggested, is a small noun pertaining to such a rich field of meanings that it seems an injustice to subject it to such linguistic containment. Despite—or perhaps because of—its diminutive size, the term ‘life’ has accrued significant currency across many fields of thought, operating more like an index for qualities of vitality, agency, sentience, and other mechanisms that we associate with liveliness or being alive. Although science has dominated definitions of its material qualities, questions about life are central to the ongoing philosophical quest for understanding the origins of existence and the relationships between beings and forms both living and non-living, animate and inanimate.

Experimenta Life Forms is a bold and invigorating foray into this arena of questions about life and the forms it takes. In keeping with Experimenta’s commitment to technology-informed works, the show focuses on the impact of science and technology on concepts of life, expanding the field in which such impact might be perceived and inviting us to rethink the way questions of life are posed. Across twenty artworks from twenty-six Australian and international artists, life is not presented as a given or knowable fact, but as an entanglement and multi-layered conundrum that is contextual, responsive and vulnerable to the forces that define it. Experimenta curators Jonathan Parsons, Lubi Thomas and Jessica Clark have selected works that put innovations in new materialism and technology in conversation with contemporary concerns about environmental damage, the limits of artificial intelligence and scientific advancement, and alignments between First Nations cultural knowledges and emergent technologies that challenge human-centric thinking.

Avoiding the pitfalls of well-worn tensions around ethics and the fetishized spectacles of ‘neolife’[i] that can sometimes beset the art/science field, Experimenta Life Forms acknowledges the complexity of such enmeshments, taking us beyond the singularity of ‘forms’ as such, towards something more like—as Thomas described it in her floor talk—‘life formations’. Situated in a contemporary context where discourses of non-truth and denialism have disrupted science’s long-held access to ‘truth’, the exhibition explores the impact of these disruptions through works that acknowledge the shifting loci of power and knowledge on a global scale. The curation offers a view from inside an ever-expanding network of human/non-human relations that is both hopeful towards a new politics of eco-consciousness and critical in its exposure of sites of contradiction and failure, particularly as they continue to play out in the environmental and biotechnological spheres. Deriving its critical power from the complex positions presented in the works, the show invites us to interact with the boundaries of a technologically mediated life, but, in doing so, consider questions of human agency and how it harms and controls as much as it creates and heals.

At the heart of the show are questions of agency. Who or what has the power to (re)produce life? How has science privileged human agency over others? And how might biological and other technologies be used to represent or enable non-human sites of agency—or, indeed, have agency of their own? Several works in the show explore these questions at a micro level where plants and bacteria feature as biological agents linked to the origins of life, or as lifeforces with their own determination. Dominic Redfern’s commissioned multi-screen video installation first forms (2020) focuses on cyanobacteria as one of the first known organisms on the planet and a building block of the evolutionary structure of all multi-celled organisms. Across several screens we witness a shifting montage of Western Australian aquatic habitats, evoking the passage of cyanobacteria across time and the rarefied saline environments in which it now survives.

Theresa Schubert’s Sound for Fungi. Homage to Indeterminacy (2020) also reflects on the imperceptible nature of micro-organic life, inviting visitors to interact with fungi in real time. Based on Schubert’s lab experiments where she discovered sound impacted fungal growth patterns, the work highlights the sensitivity of interspecies relationships, visualising the impact of sensory exchanges between organic lifeforms. Relationships between micro-organisms and environmental stimuli are also explored in Thomas Marcusson’s DJ Moss (2020), a commissioned work that playfully elevates the humble moss to DJ status, a creative agent mixing its own set of sounds based on cues from the gallery environment, sound technologies and its own internal communication system. In what feels like an eclectic and disorganised but strangely relaxing blend of field recordings and real-time sounds, the work is a complex biotechnological system, improvising new forms of entertainment for non-human and human listeners.

Beyond the real-time biologies of these works, Agat Sharma’s Brachiation on the Phylogenetic Tree (2020) and Uyen Nguyen, Max Piantoni and Matthew Riley’s You, Me, Things (2020) re-imagine microbial encounters of other kinds, using play and fiction to activate human/technology relationships. Sharma’s work, the most dematerialised work in the exhibition, is installed in the gallery as a spray-painted mobile phone number on the gallery wall. Highlighting the ubiquity of mobile communications and the spaces hidden within their structures, we are invited to call the number and respond to a series of voice prompts. Mimicking a branching structure that is familiar from both call-centre technologies and phylogenetics, participants can navigate a vast ‘tree’ of information about microorganisms, both inside and beyond the gallery. Strangely remote but compelling, the work operates as a fictional space where technological interaction is second nature, but where our relationship to microbial life forms is mediated and dependent on programmed patterns. Nguyen, Piantoni and Riley also adopt a playful approach in You, Me, Things, a commissioned digital work that produces cute ‘micro-organisms’ in response to human vocal sounds. Avoiding the constraints of language or real-life organisms, the work generates a fun, abstract, simulated space of ecological interaction based on live sound. In both works, the reliance on digital interactivity can have a desensitising effect, reminding me of the ways in which ‘the virtual space of telematics’[ii] has come to shape and sometimes overwhelm our perceptions of life, particularly in recent times.

Beyond the micro realm, other plant-based works such as the commissioned PluginHUMAN’s PULSE: The Life Force of Trees (2020) and Donna Davis’s TRANSplant (becoming Kin) (2019-2020) explore concepts of agency, vitality and adaptation in relation to large-scale forest environments. PULSE: The Life Force of Trees visualises field data from significant trees in Panama, Taiwan, India, Australia and the Amazon in an abstract ‘forest’ of networked trees. Flickering with light and sound translated from environmental data, the work offers a space for witnessing the microbial life of trees as an energetic field of movement, light and sentience. Davis’s TRANSplant (becoming Kin) explores ‘imagined ecological adaptations’[iii] in response to recent research[iv] on the displacing effects of climate change on several plant species in Queensland’s tropical rainforests. Through a series of fictionalising strategies the work reimagines the agency of the plants as they adapt to new, damaged environments. Questioning the usefulness of taxonomic conventions for understanding climate-impacted plants, Davis shows a refugee plant trying to find its kin in a library of knowledge, asking how might we consider trees not as specimens but as citizens within a global community.

More explicit attention to matters of taxonomy is explored in The Tissue Culture and Art Project’s (Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr) Biomess (2018), a work that juxtaposes archival practices of taxidermy with the experimental mechanisms of biotechnology. Amidst a selection of taxidermied specimens selected by museum curators for their unique reproductive capacities, a bioreactor containing lab-made hybridoma cells disrupts ideas of biological classification. The juxtaposition of the attractively packaged specimens and the bioreactor highlights several contemporary debates about the role of science in ‘designing’ lifeforms, and the uncomfortable relationships this has with art and consumption in a mass market. In an understated way, Biomess quietly critiques biology as a human-centric system of knowledge that, whilst pursuing progress and new frontiers, shares a boundary with spectacle and the concealments this entails.

From here, the conceptual interests of the show move towards larger macro systems, shifting from acute observational modes to the broader expanses of wonder and discovery. Kite and Devin Ronneberg’s Itówapi Čík’ala (Little Picture) (2019) hovers above viewers like a giant, alien creature, offering branches of sensitive hardware that elicit a sound response through modes of touch and manipulation. The work ‘speaks’ back to viewers, evoking an exchange of intelligences between worlds, highlighting relationships between Oglála Lakȟóta (a First Nations people of North America) perspectives and technological structures of communication. Ancient knowledges, technology and interconnectedness are also found in Daniel Boyd’s History is Made at Night (2013), an immersive video installation where shifting patterns resembling dot paintings or dust particles convey a sense of an infinite and mysterious universe. As coloured constellations shift across micro and macro scales, the work creates an energy field that is alive and complex, continuously shaped by the interactions of matter and spirit. Such expansive visions are also celebrated in Miranda Smitheram’s Macro/Micro_Whakapapa (2019) in which a 3D animated cloth evokes a transcendent energy across multiple screens. Referencing First Nations perspectives pertaining to Australia and Aotearoa, the dancing cloth evokes a mode of sentience or connectivity through which the effects of colonisation and globalisation are shared and transformed across cultures and places.

The quest for knowledge about life is explored at a greater distance by Laura Woodward in her work Planet (2019). Remote and isolated, three suspended vessels on tripod structures pump water through closed systems, evoking sustainable ecologies in their own right and recalling the quest to find water on distant planets. In a formation that reminded me of space stations or moon landings, the work evokes the remoteness of space exploration, but also the sense of an organised experiment and the possibilities of engineering planets that may support life of their own. Michael Candy’s Little Sunfish (2019) extends these ideas of engineered and self-sustaining lifeforms to a more uncomfortable level in a narrative of ecological disaster. Designed to detect radioactive material after a major spill, we see the toy-like robot ‘Little Sunfish’ escaping the confines of its duties and spreading radioactive waste through the Pacific Ocean in images recalling both the impact of an environmental catastrophe and a technological experiment gone wrong. Highlighting links between human responsibility and environmental damage, the robot embodies boundaries between human and non-human agency and control, as well as the spectre of self-destruction invested in nuclear technologies and poor environmental management. As with much of Candy’s work, the combination of playfulness and fear taps into deep-seated human anxieties that our own technologies are the root of our own endangerment as a species.

Beyond these anxieties, other works such as Justine Emard’s Soul Shift (2018) and Floris Kaayk’s The Modular Body (2016) explore robotic agency as a form of sentience, questioning the limits of artificial intelligence and experience. Emard’s video depicts two ‘Alter’ robots (created in collaboration with scientists Hiroshi Ishiguro and Takashi Ikegami) embodying a mesmerising, life-like sensitivity generated by their neural construction. The interactions between the robots suggest a kind of algorithmic empathy as data collected from the encrypted ‘experience’ of one is exchanged across generations to another, newer version. In their uncanny, human-like reactions, the robots possess both haunting and futuristic qualities, questioning the materiality of memory and sentience and the possibilities of programmed agency. This theme is also found in Kaayk’s The Modular Body where the wet-lab construction ‘OSCAR’ prompts a fictional panel of experts to discuss the ethics of biofabrication. As we witness OSCAR’s birth through 3D printing technology, the discussion highlights dilemmas about lifeforms that are self-sustaining or self-regenerative, and the new social contracts required to address issues of responsibility, rights and citizenship for the organism and its creator.

Amongst all these explorations of non-human agency, human subjects appear mediated by technologies and knowledges, decentred in the shuffling of positions wrought by scientific advancement. The more personal works both critique and celebrate the technological through different subjective modalities and personal connections. Brad Darkson’s commissioned work Smart Object (2020) explores smart technology as a disruptive and distancing force that severs connections to Country and culture, enforcing a split between the self as a cultural and digital construct. Straddling the spaces of digital and material culture, the work juxtaposes Darkson’s avatar, shown digitally ‘carving’ a plongi, with a real, hand-carved plongi displayed in the gallery adjacent to the screen. The material plongi highlights the vitality of the hand-made artefact, the evidence of craftsmanship only intensifying the dematerialised actions of the avatar and forewarning a sense of lost culture.

Helen Pynor's Capacity (2020) and Load Bearing (2021) also explore relationships between technology and embodiment in works that represent part of her ongoing investigation of body tissues and medical technologies in the commissioned Habitation (2020). Following hip replacement surgery, Pynor's work investigates links between the lithic qualities of medical prosthetics and human bone. Her X-ray-based images in Capacity highlight the body's capacity to adapt to loss and absorb new materials, reimagining human-mineral relationships as generative and symbiotic and ultimately life-prolonging. In front of these lightboxes, Load Bearing presents a white, bone-china cast of the femur head removed from Pynor's body during surgery and cream-coloured earthenware pelvis and femur bones in a display case reminiscent of an incubator or humidicrib. Through integrating her own bone material into the femur head, Pynor rethinks her body's mobility through processes of mineral exchange, highlighting the transformative potential of post-surgical bodily materials that may otherwise be regarded as waste.

Whilst the overall effect of the show is stimulating and exciting, science and technology bring with them a certain aesthetic which at times can have a sanitising effect, concealing the messiness of life, its uncontainable qualities and spontaneity. Within the show’s rich conceptual and intellectual detail, questions arose for me about how to access a more affective space, beyond the mediated interactions of algorithms and technological agents. The works that resonated most fully with this affective aspect for me were those that blended technological mechanisms with diverse sculptural materials, exploring the impact of scientific advancements on environments and communities via rich material histories and uncanny traces and resemblances.

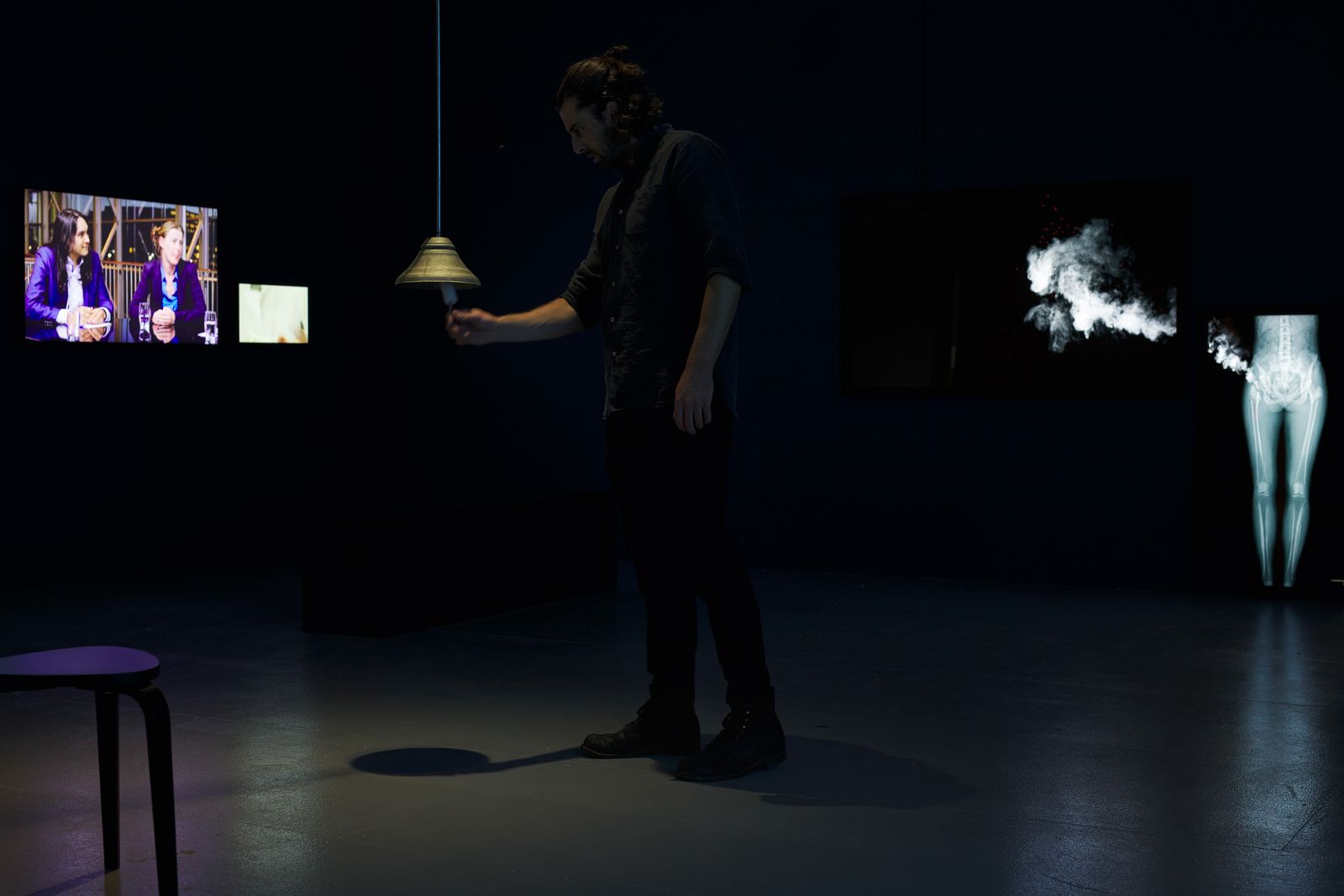

Anton Hasell’s 3D Printed Difference-Tone Bell (2017) hangs still and silent in the gallery, requiring us to activate its tone in real time. The work points to the principles of String theory which conceives of life as a series of vibrations. In the context of the show, it is a work that provides relief amongst the busyness of the other works. Printed using 3D technologies, Hasell’s bell resets the tonal range of bells fabricated via more traditional methods, subtly referencing the impact of technologies on the structure of life, but, perhaps more simply, offering the experience of a singular, unifying sound common to many cultures. Rebecca Selleck’s Snow Rabbits (2018/2020) also manages to carve out its own eery space amidst the other works. Combining new animatronic technologies with traditional domestic motifs and materials, the work conveys a claustrophobic atmosphere evoking the displaced presence of rabbits as an introduced species in Australia. Camouflaged against carpet and huddled on a chair, the rabbits ‘breathe’ under the static antenna of a snow gum branch while a regular ticking or dripping sound keeps time.

Through its mix of references the work resonates with histories of the rabbits’ survival in Australia’s harsh environment, their legacy of environmental damage and their reproductive capacity that not only saw them exploited as the backbone of the fur trade but also made them uncontrollable pests. Links between human and non-human species, communal practices and the legacies of the sciences are also found in mOwson&MOwson’s feeler (2019-2020), a strangely oppressive work displaying disembodied (fabricated) octopus tentacles strung up like cured meat. In the messiness of the installation with its entanglements of cables and alienated limbs crawling with lights, the work conveys a complex history of exploitative methods of industrial farming, and an uncanny reminder of pathogen transfer between humans and animals.

Throughout the exhibition the decentring of the human subject is key to the critique of anthropocentric viewpoints, but therein lies a contradiction: all technologies, productive or destructive, are our very own. Ultimately, the show refuses to resolve this contradiction, suggesting rather that we must face the challenges such contradictions present, and find ways to adapt, evolve and act towards a new ethics of care and responsibility in an ever-expanding spectrum within which life is generated, defined, and experienced. In the diversity of works, the exhibition challenges us to consider the limits of affect and empathy in a world where technology mediates our relationship with each other as well as non-human agents, potentially reinforcing synthetic modes of interaction and notions of life as programmable, manipulable and replicable. At the same time, it invites reflection on life as something beyond all these systems and structures, a complex and mysterious force that varies and changes over time, in which we are but mediators in a continuum of exchange and transformation. In all the energy ebbing and flowing throughout the show, Experimenta Life Forms impressively captures the ‘eco-mess’ of the current climate and the evolution of a language in which the word ‘life’ references increasingly complex and entangled formations.

FOOTNOTES

[i] ‘Neolife’ is a term devised by Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr to describe life forms resulting from laboratory practices that become separate species restricted to particular environments. Such life forms are oddities that may share an origin but develop their own unique characteristics as a result of scientific intervention. For more information, see https://tcaproject.net/portfolio/neolifism/

[ii] Kac, E. (2005) Telepresence & bio art: networking humans, rabbits, & robots. University of Michigan Press. p. 8

[iii] Donna Davis, 2020, https://donnadavisartist.blogspot.com/

[iv] Davis’s TRANSplant (becoming Kin) draws inspiration from the ‘Tropical Mountain Plant Science Project’, a realtime environmental flora rescue mission led by the Australian Tropical Herbarium.