Janet Maughan: Opening remarks, 11 December 2020

Distinguished Guests, I acknowledge that we are standing on Kaurna Land. I stand here today, as a friend of Annie Newmarch, who has been actively engaged with her life over the last several decades.

My family were boat people to South Australia 173 years ago but I still cannot put my hand on my heart and say “This is MY country.” I have no tribe that makes marks that are mine – that are made for me, or of me or by me. There is no mark making that includes me or speaks to me in important and significant ways. But I do have the works of Ann Newmarch over the last five decades.

For me, and for thousands of others she has articulated our sense of place, our sense of belonging and our sense of tribe. And this matters. When we are struggling to comprehend the issues in our lives we turn to images and stories that speak to us, that communicate with others and that make connections.

And in a culture that locates women as “other”, Annie Newmarch has explored for us through her images of the female body, issues of sexuality, of beauty, of pressures to conform, of idealism and reality. She has visualised for us a systemic analysis of feminism. She made real the tensions within the domestic sphere particularly when motherhood and all its responsibilities became a reality.

For how could you be a radical separatist if you were the mother of sons? Remember – it wasn’t until 1973 (and through the pressures of the Vietnam War) that the age of adulthood was reduced from 21 years to 18 years of age. Boys at that time were old enough to kill but not old enough to vote. Annie was painting the images for Red Gum’s “We were only 19 …”

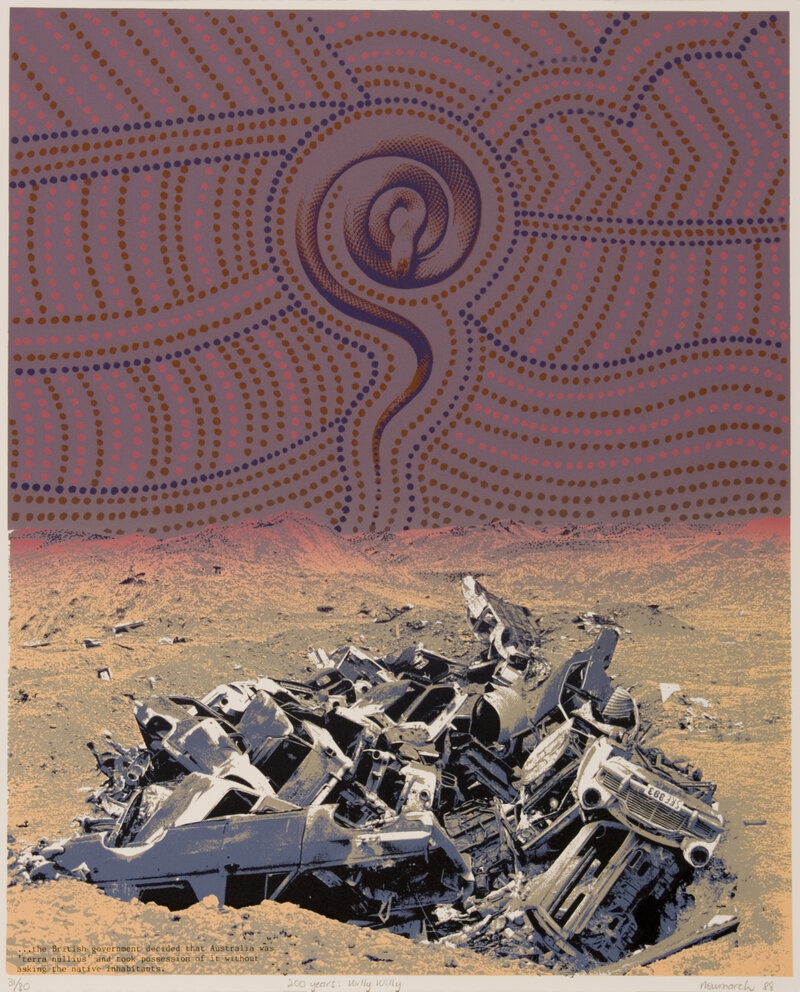

She tackled workplace inequalities, raging against capitalist exploitation – gaol bosses not workers – and railed against inequalities of unequal pay for equal work, a situation not yet achieved! She explored Indigenous issues and where we might fit in the oldest living culture with her images of beer bottle spear tips and wrecked cars littered across an ancient landscape – as the Serpent Struggles series.

And in recent years as we aged, she examined human frailty and cultural patterning. She explored for me issues that I was and am struggling with. She gave me a sense of place and an identity.

It is right and proper that this exhibition – a selective survey of her last five decades –is staged in her beloved Prospect and put together by a clever young woman, Sarah Northcott, who is taking Annie’s legacy into the future. By showing us the range of issues that Annie addressed and the ways that she explored both the depths and the subtleties, our understanding is enhanced, our communication is strengthened and our connections are forged.

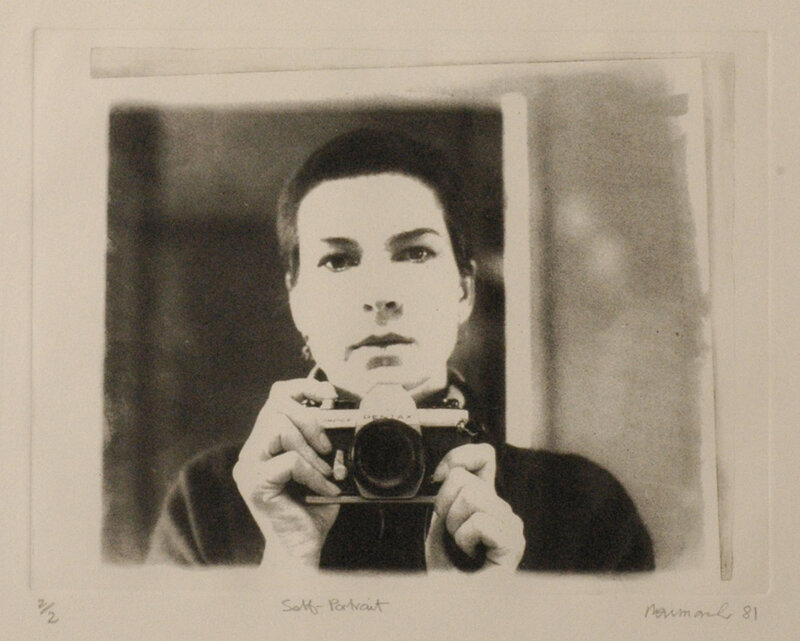

Before you explore the range of works that Annie has created let me tell you a little about her life. Ann Newmarch OAM needs little introduction. She has been a practising artist since 1969 with a major retrospective at the Art Gallery of South Australia in 1997. She has held more than thirty solo shows and participated in more than one hundred significant group exhibitions. She is represented in all state galleries and in major private collections.

From the first that she can remember Annie loved drawing. It was she (at times with others and perhaps developing her adult sense of collaboration) who did the Christmas decorations at school each year often with just three Leviathan crayons (remember the red and white striped box?) using just red, yellow and blue.

She wanted to go to art school but family pressure forced her to leave school at the age of 14 and get a job in a pharmacy. Her mother wanted her to make herself pretty, marry an accountant and have four children. This wasn’t for Annie. She said that she used to trade her white pharmacy uniform for the black worn by Beatniks to go to jazz clubs in the evenings in the city.

She did continue with life drawing classes each Thursday evening taught by John Dowie during this time. She desperately wanted an education and to be an artist so she returned as a mature age student to Brighton High School graduating as a 21-year-old to go to Western Teacher’s College.

In 1967 at 22 years of age she submitted works to an exhibition at the Contemporary Art Society of South Australia and then went on to have her first solo show. The art critic of the time, Lou Klepac, would not review her show. And when Ann asked him about this he told her that “she was a woman, she was under 30, she would fall in love and have babies and as such she was NOT a good investment”. How wrong he was!

By 1969 she had secured a position at the South Australian School of Art, hard won against opposition by her male colleagues. She did not marry but did go on to have three beautiful children and practised her art alongside the demands of motherhood, with her experiences informing her images and speaking for so many women.

These works documenting the children and their relationships to each other, valuing their hair and their teeth (as many of us secretly did), made public for us an identity as women and as mothers.

To me and many, many others she was speaking to us and for us. She was making our marks and her sometimes harsh portraits showed us that there was no easy path.

She was also hugely engaged in community arts, particularly in Prospect with the painting of Stobie poles and challenging murals, ceramic tiles embedded in footpaths, discussions about various environmental impacts and the development and support of a local art gallery with her local city. (Those of us living outside the district often felt a twinge of envy at the activities within this local government area).

Ann was a co-founder of the Progressive Art Movement and an active member of the Women’s Art Movement and for all these activities she was recognised with the award of the Order of Australia Medal in 1989.

Of course she valued this recognition but what pleased her most was the Art Gallery of South Australia’s retrospective of her work in 1997, The Personal is Political.

The flagship image for this major show is Women Hold Up Half the Sky (1978) created for her Auntie Peg who built a house on her own while raising eight children and working two jobs.

This image was awarded an Australia Day Award in 2010 and in 2019 Annie was highly commended in the Ruby Awards. She believed she had come full circle as it was Ruby Litchfield who coached Annie for her presentation as a debutante to curtsy properly!

The fundamental tenet of her work is that the personal is political. In fact all representation is political and the absence of a voice is in itself an acceptance of the status quo.

Annie wants us to read the images, to think, to discover and to make connections. Even her highly decorative works for her last major solo exhibition on cultural patterning and human fragility (2010) capture complex surface decorations but embed clues to deeper meanings. She connects ideas and events across time and place and across cultures both east and west.

She always wants us to think and to make connections for ourselves but she will provide keys for us. Her exhibition will reward close inspection and reflection.