Warm sunshine greets as I park my car in the quiet tree-lined street. Nearby, the River Torrens winds silently through the inner sanctum of Adelaide. This is Kaurna country; Kaurna are the original and traditional people of this land. It is our protocol to acknowledge Kaurna, the continuum of connection to land and the strong ongoing cultural presence. Kaurna are generous in their teaching, that this area is Tarntanya, an ancient meeting place on the banks of the river Karrawirra Pari. I walk along North Terrace toward the modern arts precinct. The annual Tarnanthi exhibition is about to open showcasing significant new and diverse artworks from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists across the nation. Tar-nan-dee is a Kaurna word, meaning to come forth, or appear like the sun. It is the media launch event. Media are gathering to hear the words of Nici Cumpston OAM, the Artistic Director of Tarnanthi since its inception in 2015, who works alongside a visionary team of women including Lisa Slade (Assistant Director, Artistic Programs AGSA) and Mimi Crowe (Producer, Tarnanthi).

.jpg)

Ascending down the large stairwell set in the West Wing of the Art Gallery of South Australia into the Open Hands exhibition I am instantly captured by four immense amatory sea-blue fabric cyanotypes, an alluring dive into clear waters, down to the reef below, to touch the tangible knowledge portrayed here. At the bottom of the steps I am fortunate to meet the creators who, due to the health risks and travel restrictions of Covid-19, are the only two artists in physical attendance. Sonja and Leecee (Elisa-Jane) Carmichael replicate their art through their fervent, gentle presence as mother and daughter, strong Quandamooka women weavers from Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island). An aura abounds as they speak; their words carry the winds of connection, the sensory scent and sounds of deep water and sand, their love of Home.

Together their hands have gathered natural elements and marine debris, layered carefully to define these blueprints, the placement of objects allowing an individual presence, a language like words that sign a cultural salvaging against derogative terms of the past, cultural presence as a form of resistance transposing against the current. Their hands follow the familial knowledge of their matriarchs; their artworks tracking their cultural path. Sonja and Leecee are regenerating truth-telling, tracking Quandamooka flat baskets long held captive in anthropological holding booths, both in the Queensland Museum and overseas; always their artistic purpose is to reclaim and regrow. Their research clarifies; weave knot holds an identity, captivating a moment in time, like a portrait. Hold that knowledge in your heart. Feel the passion and values of cultured women. Stand here and know that an interruption is being repaired. mara milbul wuryay (hands alive today). Stand before the magnificence of this thought, witness the manifestation. I smile that mara means the same in Quandamooka and Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara languages.

Sonja and Leecee Carmichael’s cyanotypes are the perfect introduction to Tarnanthi; in 2020 the Open Hands exhibition holds an important focus of women, their relationship with each other; as mothers and daughters, sisters, grandmothers, knowledge holders, children, a legacy to the future as an honouring to the past through the passing of knowledge from senior artists to the young. A quiet energy can be felt in this gallery, alive yet buried in this underground womb of creative resistance and feminine resurgence. The energy calms, reminding to wander slowly, to observe from within.

.jpg)

In an adjacent space Mara ala is revealed. Mara ala (of traditional healers) able and competent. Betty Muffler and Maringka Burton are the artists, two senior women ngankaris who live in Indulkana on the APY Lands in northwest South Australia, where my Kami (my mother’s mother) was born. Their relationship is sister-sister, and they have collaborated to create intricate new works on paper. On opposite walls, above two of their collaborative pieces, individual statements are boldly emblazed to further explain. Maringka states: “We have done so much work together as healers, but this is the first time we have painted together. We both started off painting on our own, each of us painting the Country where we were born and belong. These places are an essential part of each of us.”

Betty reiterates “The painting is about healing the sick, our work as ngangkari and the way the two of us work together as ngangkari. We two women are healers, we have the hands to heal.” The large works on paper are documentations of country, thin moving lines drawn behind larger traditional iconography, some areas cloudy like the sky. I am reminded of the night sky and beyond. The black-on-white, white-on-black works exude a powerful vibe. I feel overwhelmed, to tears. I know these women through their tireless work with the NPY Women’s Council. Maringka has been one of my healers and cultural mentors through Women’s Law ceremony in the desert. The healing energy reminds to observe slowly, to wander within. I fill with the gift of memories from the past. These artworks exude healing and I must rest.

The following week I revisit AGSA to meet one-on-one with Nici Cumpston. It is an opportune moment, decades overdue; Nici was my photography lecturer at Tauondi Aboriginal Community College in Port Adelaide in the late 1990s. We recall many happy, often hilarious memories of that poignant time; this was the time I first met my birth mother, sadly Nici’s beautiful mother passed the following year. It feels fated to share this exact moment together; teacher and student, director and reviewer. Open Hands is an essential snapshot and testament to the handing down of knowledge from one generation to the next. This is true Indigenous practice.

A highly successful Barkindji photographer, Nici encourages the photographic reclaiming in Open Hands. Naomi Hobson is a Southern Kaantju/Umpila photographer who lives in Coen, in the heart of Cape Yorke Peninsula, where her mother, her mother’s mother, generations of mothers, have lived before. By visual invitation Naomi Hobson reveals her community, far beyond its existing identity as a police town and reserve, reframing it against the ignorance and prejudice that Australia has narrated in its archived photographic past.

Hobson’s vivid imagery is fresh and joyous; the maturity of her craft both clever and concise. In the gallery thirty-one prints are displayed to walk amongst in street-like fashion, every image another house, another view. This beautiful series titled Adolescent Wonderland portrays the youthful adventure and optimism amid the young people of her community, all subjects intimately known to the artist. Props include masks, wigs, a blow-up floatable flamingo and paddle pool, to create vibrant colour portraits set inside a black-and white background, highlighting presence in the modern day, a presence that has always been lived in country, a presence of pride. All images are titled to reveal. A favourite is Banned: “I'm banned from that store for a week ... I don't care. I'll just keep riding past to the next shop.” (Amos Jnr). The young man is paused in the middle of the road, looking back over his shoulder. An Australian flag extends along the front verandah of the store. Such a powerful image and metaphor!

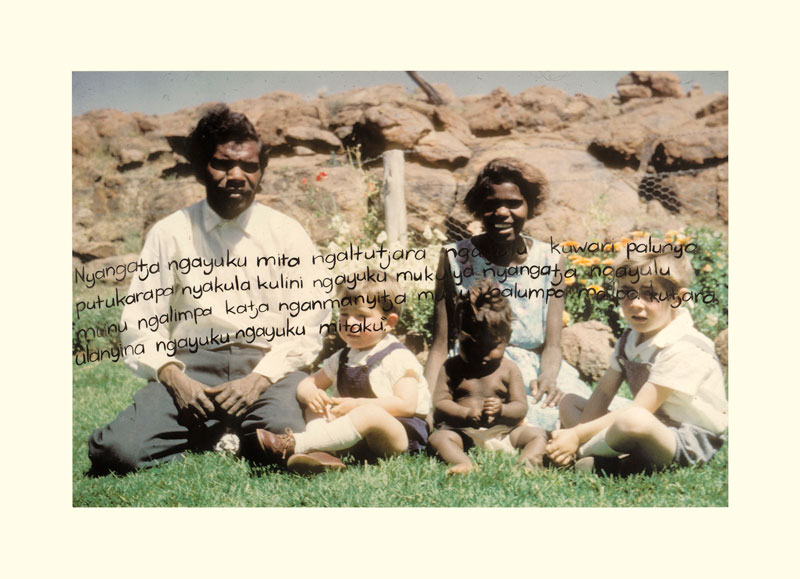

As a Yankunytjatjara poet, I rejoice the “written words” artworks by two senior artists from South Australia. Nyurpaya Kaika Burton is a respected Anangu leader from Amata, in the APY Lands. During Tarnanthi 2016 I was privileged to host an inimitable conversation with Nyurpaya, assisted by language translators to discuss her innovative personal writings. Her continuum is extraordinary, using coloured prints from reversal/slide film of her early family life and younger years that were probably captured by the missionaries and staff at Ernabella. Nyurpaya has reclaimed these images with her own hand, scribing across these archival moments in time.

She has added new depth; all words are in her traditional Pitjantjatjara language. Nyangatja ngayuku mita ngaltutjara ngayulu kuwari palunya putukarapai nyakula kulini ngayuku mululya nyangatja ngayulu munu ngalimpa katja nganmanyitja munu palumpa malpa kutjara ulangina ngakuku ngayuku mitaku. As the audience it is important to peer within, translating with one’s eyes and heart the insight of these deep, delicate snapshots. Read the original language verse using a softness of inner voice. Remember the happiness shown here, the absolute love of life and lack of fear for the new, the friendships and sharing of children without removal.

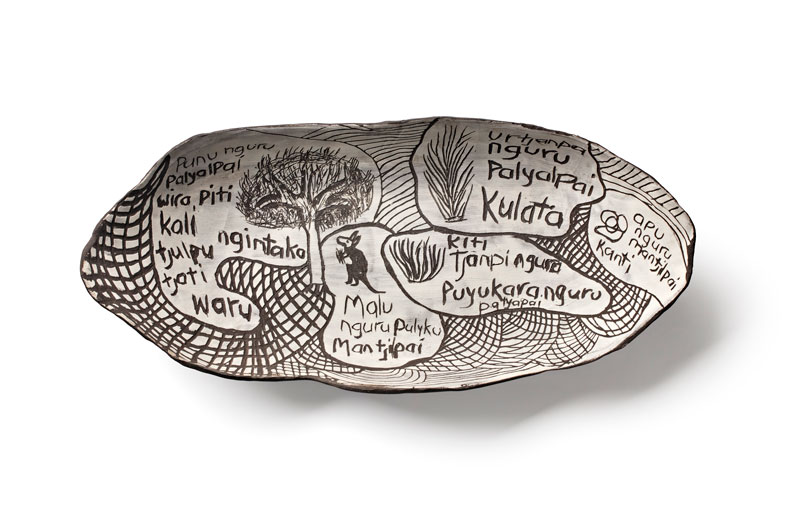

Ceramics is the medium displayed by Tjunkaya Tapaya OAM, a leading senior artists from Ernabella Arts in Pukatja, in the APY Lands. Using original Pitjantjatjara language, Tjunkaya has carved words into the clay, printing sacred stories and stories of the everyday, presenting a series of vase-like pieces and a coolamon decorated with traditional art more commonly seen in paintings. The effect emphasises the re-imaginings of old practices into the ever-changing times of today, another dimension to narrate and share cultural knowledge and stories.

Another favourite find was amongst the animations from central Australia, fielded from Tangentyere Artists and the town camps of Mparntwe, Alice Springs. The short film Ration Day to Pension Day features the animated artwork of Doris Thomas. Through her beautiful representative paintings Doris reveals life on community amongst the sand hills in the olden days, painted portraits given life and narrated by herself. I listen carefully to her voice. I have heard it before; my grandmother employed Doris as a teenager, through an initiative of the Lutheran Church when I was a little girl. Desert humour is so loveable; “one of the sheep was named Damper, he was always trying to eat damper.”

Other Mparntwe-based artists featured in this series are Betty Nungarrayi Conway and Grace Kemarre Robinya, and Western Arrernte/Luritja artist Trudy Inkamala from Jay Creek. Trudy shares her grandmother’s memories and has portrayed Old Laddie and Old Polly on works on paper, modifying her grandmothers clothing from ration quality to vibrant high-fashion with thrilling hairstyles. It is clear here, Trudy's humorous recounts are driven by the absolute love of her grandmother.

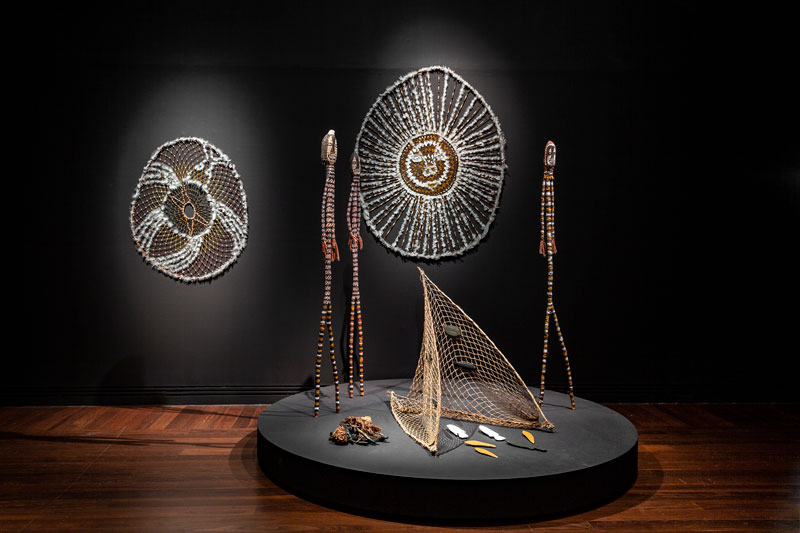

In a slightly darkened and separate space I spot a large feathered mandala on the wall. Lena Yarinkura and Yolanda Rostron, the artistic mother–daughter duo from the Kune and Rembarrnga people of Arnhem Land offer a profound installation of Ngalbenbe (the sun), using sculpture, painting, song sound and raw materials. This is an epic narrative work sharing ancient cosmic knowledge of their fishing customs. Kadjok, Bulanj and Kammarang are fishermen and the telling explains their relationship with Ngalbenbe to increase their catch. At their sacred place fish-increasing spirits assist, binding the duty to share and celebrate with ceremony.

It is a complex telling; a narrative from long before any foreign interruption, the creation world beyond the Bible. One can feel a pure love in the telling; a respected closeness and understanding with the natural world, an honouring and responsibility that is rarely known outside Indigenous custodianship. The importance of this telling is reinforced by gentle song sound, chanting by Lena’s husband Bob Burruwal. This ancient song moves like the sea, tides coming in and out, as if representing generations of humankind. Tarnanthi means to come forth, like the sun. Lena is a shining example, teaching her children and grandchildren, knowing she will one day fade and they will emerge.

Open Hands is a big exhibition. There are so many deep stories here and such a variety of mediums to discover. Admire the intricacy of the ceremonial mindirr (dilly bags) from Yurrwi Millingimbi, the beauty of the Wankuru installation, the celebration of Kapi. Watch out for the mamus and witches. The sharing of Aboriginal cultural knowledge and ideology creates a beautiful and warm atmosphere; the collective magnitude of these works by women is exceptional and powerful. Always there is the faint accompaniment of singing. Remember to wander slowly, to listen and observe from within.