Let me take you on a trip

Around the world and back

And you won't have to move

You just sit still

Depeche Mode, “World in My Eyes”, 1990

In the opening weeks of COVID-19, when everything teetered on the cusp of strangeness, Cognitive Dissidents: Reasons to be Cheerful promised a form of escape. The exhibition, curated by Stephen Jones, presented twenty-four works of Australian (film and) video art. Walking through the Queensland College of Art to the Griffith University Art Museum, the quieter-than-usual campus indicated that the artworld was already #stay[ing]safe by #stay[ing]home. In these unusual circumstances, an exhibition of video art provided a double haven: offering a physical reprieve from the new practices and anxieties of social distancing; and a mental distraction from the up-to-date news coverage and commentary filling so many of the other screens in our lives.

Bush Video’s Meta-Video Programming (1974) was projected onto the gallery’s far wall. Psychedelic colours stretched and danced. In his catalogue essay, Jones explains that this work harnesses video’s capacity for self-generating content. The work was made in part by pointing the camera at its own feedback monitor, a medium-specific feature that makes video distinct from film. The lurid shapes of Meta-Video called to mind Depeche Mode’s song “World in My Eyes”. In the otherwise quiet gallery, this imaginary, sex- and drug-fueled soundtrack heightened the exhibition’s connections with memory and nostalgia; and it struck me that the song, this work and the exhibition revel in the act of sitting still and recovering known ground. As I think through Cognitive Dissidents, these counterpoints return again and again: the physicalities of stillness, presence, focus, containment and lockdown versus, or in conjunction with, the intangible freedoms and vastness of our minds. Jones’ exhibition maps these two realities. His exhibition design attends to the limits of the medium while his curatorial selections map their possibilities.

The gallery walls painted a clear blue – the shade of a cloudless sky in Alice Springs – marked out the gallery as neither White Cube nor Black Box, a subtle indicator that the works in this exhibition are not the singular, precious objects of art history or the mutable digital files of the contemporary world. At standing-eye height, small flat-screen monitors dotted the gallery’s perimeter, each accompanied by a pair of headphones. Their dimensions approximated the original viewing sizes of the works. On the gallery floor, a further cluster of four works on older CRT televisions were arranged in a cross, their boxy backs to each other and a singular stool at their feet. This exhibition design prescribed the solitary foundations of the exhibition: requiring visitors to watch one work at a time and asking them to watch alone. GUAM Director Angela Goddard observes that this is the viewing norm of another generation. Eschewing exhibition designs that repeat the layered bleed, cacophony and spill of contemporary life, where neither home, workplace nor street corner is digitally quiet or focused, Cognitive Dissidents prioritised discrete viewings. Bespoke partitions added to the gallery walls physically angled the videos away from each other, further ensuring this concentrated view.

Cognitive Dissidents ran to over four hours viewing time, warranting multiple visits. Earlier in the year this seemed possible. Almost half a year later, amidst international gallery closures and Australia-wide university lockdowns, it wasn’t. On my second visit, I attempted to spend time with each work, to move around the room methodically, yet found myself buffeted by the asynchronous start and end times. Like an escaped subject from Geoffrey Weary’s video, I glitched. Weary’s Museum (1996) documents gallery visitors to the Louvre. The work collages dramatic, close and stuttering observations of audiences with the neoclassical paintings of their gaze. The soundtrack, described as “large piano chords in the lower register … struck slowly and regularly,” imbues the documentation with a thriller-esque menace, conjuring allusions to spying and entrapment. A “short mid-register arpeggio,” described less formally in my notes as fast-paced computational output sounds, adds an uneasy sense of urgency. Like the subjects of his work, trapped in repetitive encounters with Jacques Louis-David’s Oath of the Horatii (1748), my movements were less successful than intended, as I re/encountered the same segments in videos on repeated viewings.

Each time I approached Frank Osvath’s Homage to John Cage I caught the opening scenes: flashes of white light barrelling across the black screen from left to right. Determined to hear the text of Cage’s poem “I have nothing to say and I’m saying it” as described in the exhibition wall text, I returned to it between watching other videos. As I zigzagged amongst them, I observed the same underground rail scenes of Linda Wallace’s lovehotel (2000), the same cropped teacup and kettle of David Perry’s Interior with Views (1976) and the same opening titles of Merilyn Fairskye’s Eye Contact (2000). Finally, I caught the white lines of Osvath’s work oscillating wildly across the screen, a highly energised visualisation of Cage’s drawling nonsense poem.

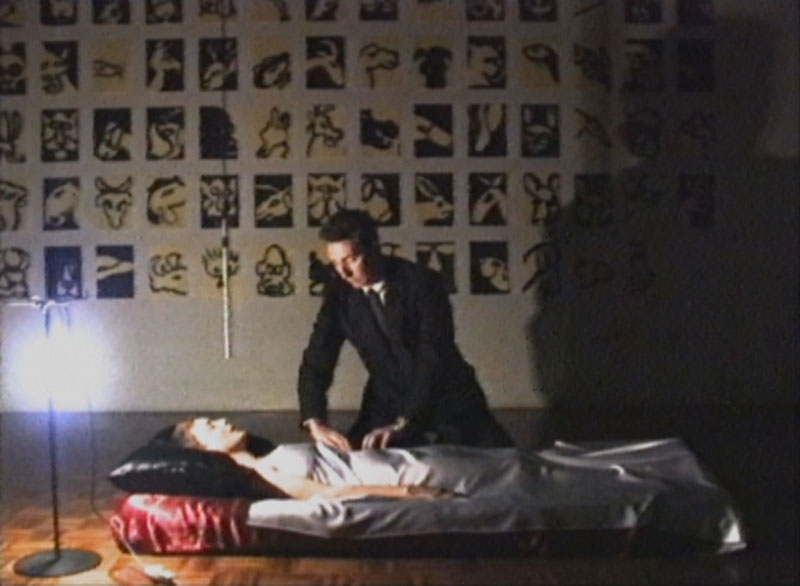

The same dogged persistence marked my viewing of Barbara Campbell’s The Seduction of Art (1996). Lying in a gallery upon a makeshift bed of black, white and red satin, the artist retells the story of seeing Jackson Pollocks’ Blue Poles at Brisbane City Hall when she was thirteen years old. Campbell talks slowly and with attention to detail. Meanwhile, a suited man brushes his hands up and down the length of her torso. His movements are curious and captivating, part massage and part caress. Campbell’s work similarly strikes a delicate balance between conceptual dryness and affective connotations. At each of my returns to the video, I encountered Campbell in what I imagine to be the first half of her story – in King George Square, climbing the steps of City Hall, moving past other paintings by other men – but never in front of Blue Poles. Viewing works in a gallery, without access to the remote control, heightens our awareness of the medium’s temporal dimensions. It highlights our commitments and availabilities (or not) to viewing them.

Jones describes Cognitive Dissidents as an exhibition that “looks at the range and possibilities that video opened up during its first two decades in Australia.” Jones knows, and is a part of, this history. His knowledge is made clear via his catalogue essay, which confidently reports one history of video art in Australia. Jones’ involvement is modestly tucked into footnotes and image credits. These reveal his role as technical assistant to Nam June Paik and Charlotte Moorman for their infamous 1976 Kaldor Art Project and, more recently, his role in digitising all of the works in exhibition. Rather than offering a definitive history, which might curtail selections, Jones’ curatorial premise feels expansive. It offers the works room to breathe and feels open to addition.

Jones’ curatorial hand is perceptible in subtle connections between works and their placements. Illness links Jill Scott’s Continental Drift (1989) to Francesca da Rimini and Josephine Starrs’ White (1996). Pollock features in Campbell’s video and reappears as lashings of white, red and blue paint across r e a’s body in Poles Apart (2009). The colonisation of the Australian landscape ties together Joan Brassil’s Kimberly Stranger Gazing (1988) and Peter Callas’ Night’s High Noon: An Anti Terrain (1988). More overtly, Jones’ selections make an argument for video’s difference. The opening words of his exhibition catalogue read: “Video is a medium of experiment.” The works on show demonstrate video’s varied intersections with medium-specific abstractions, computer graphics, internet poetry, magic realist narratives, performance documentation and photographic collage. A highlight of the exhibition catalogue is the detailed descriptions of the sound component of these artworks.

Diversity of form mirrors the exhibition’s concerns with dissonance and dissidence. Warwick Thornton’s 1996 short film Payback presents an alternative model of justice. Chanting feminists in Jeune Pritchard and Luce Pelissier’s Queensland Dossier (1978) give clear voice to counter-cultural views while Debra Beattie’s hilarious Expo Schmexpo (1986), featuring Joh Bjelke-Petersen impersonator Gerry Connolly, equally criticises state politics. These three works, exhibited in close proximity to one another, resonate in the present. They provide a long history for #BlackLivesMatter marches and their attendant calls to abolish the industrial prison complex. Connelly’s Bjelke-Peterson calls to mind Donald Trump’s incoherent speech.

While other galleries scrambled to digitise exhibitions, GUAM opted against virtually recreating this exhibition. The works’ digital format makes this decision seem counterintuitive but to move this exhibition online would be to lose the very deliberate curatorial decisions to view the works in a physically pre-determined way. Moreover, online streaming through gallery websites sits at odds with a generation of Australian artists who may still, and with good reason, be suspicious of institutions, which in the early years of video art were still looking overseas and to the past for their definitions of “art”.

Cognitive Dissidents argues that even digital artworks deserve tangible encounters and reminds us that galleries allow unique ways of being in the world. Neither of these are easily replicated online. This is not conservative advocacy for galleries as quiet places of ritual. I welcome halls filled with motorbikes and slippery dips, places for loud children and louder performances, rooms for debate alongside walls for archives. I mean galleries as places that allow us to contemplate, experience wonder and feel. Which brings me to twinned concluding thoughts. Let’s do everything we can to open galleries sooner. And we must work meaningfully toward ensuring that everyone feels welcomed, even cheerful, within their walls.

Griffith University Art Collection. Purchased with assistance from the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body, 1996. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne