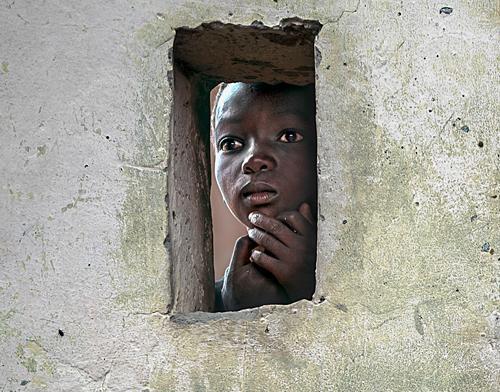

Shahidul Alam: You’re blocking the sun

I don’t want to be your icon of poverty, or a sponge of your guilt. My identity is for me to build, in my own image. You’re welcome to walk beside me, but don’t stand in front to give me a helping hand. You’re blocking the sun.