Weaving memory, living embodiment

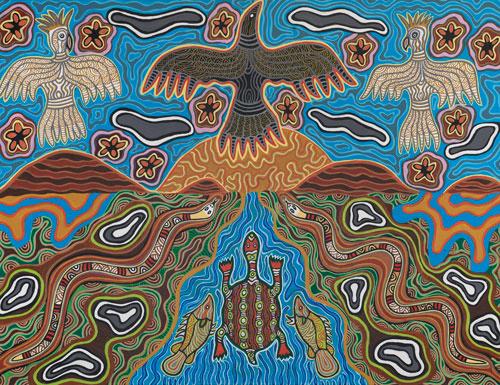

Standing proudly in front of the three Gulayi women’s bags woven by my mother and sister, Sonja and Elisa Jane Carmichael, in the Australian art collection of the Queensland Art Gallery, I look back to my very first experience with Quandamooka fibre work. My significant engagement with the Queensland Museum collection reunited me with the bags and baskets woven by the hands of our Ancestors from Quandamooka and introduced me to the work of other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from near and afar. In the presence of these spirited works I was reminded of the expansive visual language, meaning and innovation of artistic traditions belonging to our First Nations communities. Each woven basket and bag, looped net and intricate adornment or string work reverberates with a strong sense of place and shared stories of people and Country.