From desert artists there has been nothing like the work of Kunmanara Mumu Mike Williams, combining Aboriginal iconography with maps, ironic repurposing of materials, his own texts in Pitjantjatjara with interventions in received texts in English. The work is visually exciting, intellectually engaging, moving and explicitly political.

Kunmanara Williams did not wait for his message to filter out from art contexts, but asserted his voice directly into the political process. For instance. he made a submission to the South Australian Government’s recent Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission, from the perspective of someone whose land and people had suffered harrowing detriment during the British atomic tests of the 1950s and 1960s. He had a profound sense of mission for his life and work, putting it this way at the Desert Mob symposium in 2017: “One day I’ll die, for the country, and that’s why I write Pitjantjatjara, tjilpi and pampa look after country and Tjukurpa. When I die the children can take over for the land and Tjukurpa.”

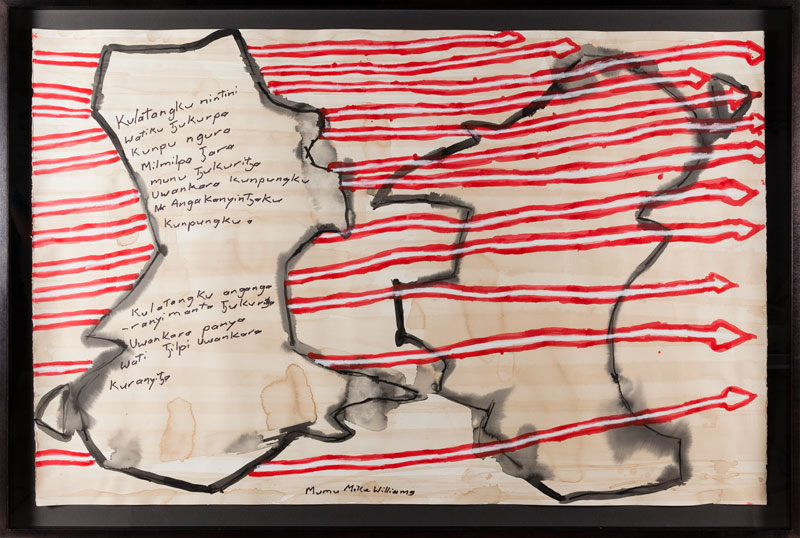

The spear – kulata – was a central image in his work and a metaphor for his mission, to preserve and protect Tjukurpa, inseparable from manta, the land, and its custodians, the tjilpi and pampa, senior men and women. “The spear is our culture … we live by the spear,” he said briefly but eloquently the first time I heard him speak in 2016 at a Mimili Maku Arts show at RAFT Artspace in Alice Springs. “No whirlwind can push away the spear. Our Tjukurpa is like that,” he said in March this year, at the opening of Weapons for the Soldier at the Araluen Arts Centre, the region’s major public gallery. Then he made the metaphor more explicit: “I’m not talking about whirlwind, I’m talking about something that tries to push away our story, like politics … Any politics can’t push our kulata away, our story is strong, it’s the kulata story.”

We have run out of opportunities now to hear Kunmanara speak. Sadly, he passed away later that same month. But his legacy is preserved in his paintings and in a book that he was working on at the time of his death. It was launched in October at the APY Gallery in Adelaide as part of the Tarnanthi program, South Australia’s Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art.

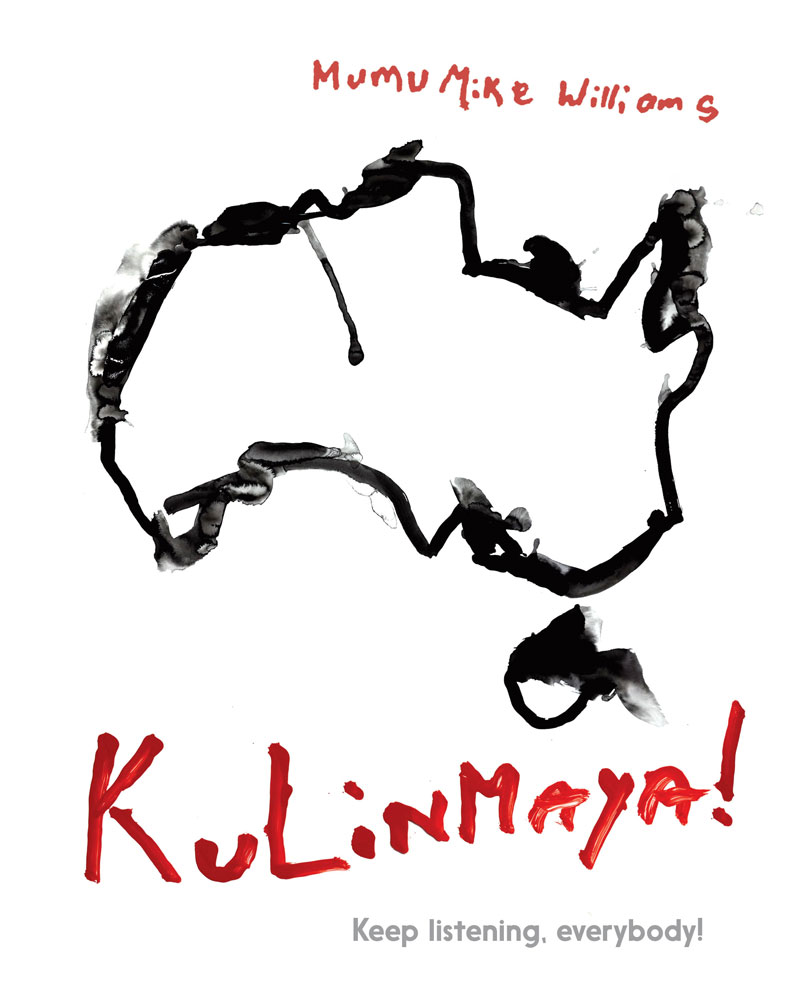

The book, Kulinmaya! – meaning “Keep listening, everybody!” – is a joy to read and look at. At a time when we are becoming ever more aware of the often cruel and tragic experience of Aboriginal dispossession, it is consoling to read that Kunmanara’s memories of childhood at Ernabella Mission were “wonderful” and to see the visual evidence of that in photographs – for instance, his exuberance as he rounded up sheep with his cousin-brother, Tjilari Edwards, and as they rode bareback on donkeys. It is striking that they are entirely naked in these delightful photos. Their teachers would not let them wear clothes, we learn, to keep their skin healthy. Nor were they allowed to learn English early, instead taught to read and write first in Pitjantjatjara. (This would bear powerful fruit in Kunmanara’s later art-making.) If only this basic respect for Indigenous language, culture and way of life had been more widely shared.

On the weekends and holidays, they were discouraged from hanging around the mission, Kunmanara recalls. They would go bush with their families, walking everywhere, everyone fit and healthy, hunting and gathering bush foods. He describes their diet as “delicious”: goanna and perentie, figs, desert raisins, bush tomatoes, wild gooseberries, witchetty grubs. His mother would bake wild bush seeds and grains, like woollybutt and wild millet. There are precious photographs from these times, most of them sourced from the Ara Irititja archive, an invaluable cultural resource for Aṉangu – the collective name for Ngaanyatjarra, Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara people. The archive holds their private cultural history and only Aṉangu have open access to it, but the book provides a great glimpse into its treasures.

This happy early life, closely in touch with country, kin and culture, provided the grounding for Kunmanara’s clear vision for his life as a young man. He earned his living in the new economy, doing stock work and making bricks, describing it as “good work”. But Aṉangu ways remained at the centre of his life. Those young men who didn’t listen to their grandfathers have died young, he says, warning against the distractions of city life, such as the casino. He describes his experience of becoming a man, in the tawara camp, “hidden and distant”, segregated especially from women, including grandmothers. The main task for the newly initiated is to go hunting, and to learn to cook the meat the proper way. In this, he was taught by his older brothers. “The mothers and fathers are always so proud of their tawara sons … also knowing their older sons are there, caring for them.”

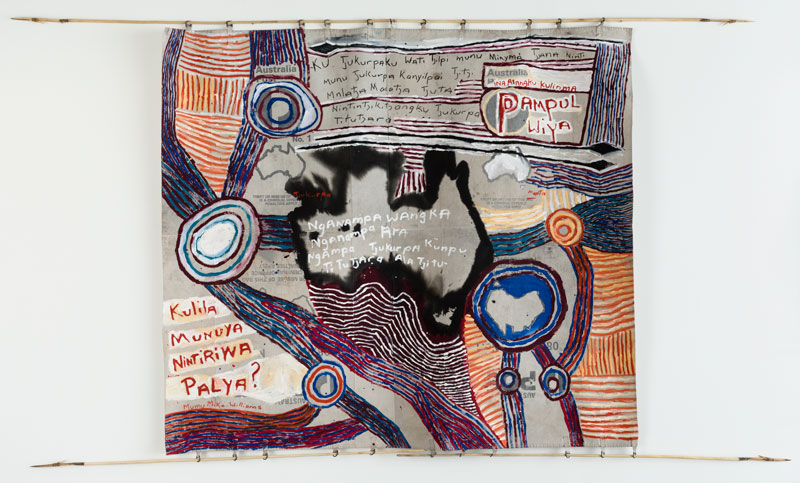

![Kunmanara Williams and Sammy Dodd (spears), Pina Alangku, 2018. The painting surface is canvas from mailbags and part of the work is an intervention in their proprietorial text, so that it reads: Theft or misuse of this [bag, crossed out, replaced by manta] land and its cultural heritage is a criminal offence. The Pitjantjatjara text in English: Open your ears and listen.The senior old men are the ultimate bosses.](/uploads/articles/M_M_Williams_3.jpg)

Kunmanara recalls his family in the support camp speaking a special ceremonial language during this time. He recalls being taken to see sites of great significance, learning the rules around who can go there, the importance of waiting for the traditional owners to go in first. Only they had the right to take water from there; fire should never be lit near these places and if it is, it must be put out with water by senior men. He returns to the same theme, again and again, in the book as in his paintings – the enduring power of Tjukurpa, and opposed to that, the untruth of terra nullius. He uses this Latin term himself in his Pitjantjatjara speech (the book is chiefly composed of recorded accounts by Kunmanara, expertly translated by Linda Rive).

So, speaking of his core messages, he says: “I am also writing my response to something one man once said. A man who was a stranger to this land. Many years ago, this man stated that Australia was an empty land, terra nullius. What he said was wrong. We are many people, with an enduring and powerful culture. What he said is simply not true.” Not true then, not true now. He emphasises Aṉangu knowledge of their country: every rockhole, every water source has a name that children continue to know, together with the associated stories and, at key sites, prohibitions. Contrary to popular belief, Kunmanara asserts and is “glad to say” that much of Aṉangu traditional lifestyle has not disappeared, and many important skills continue to be imparted.

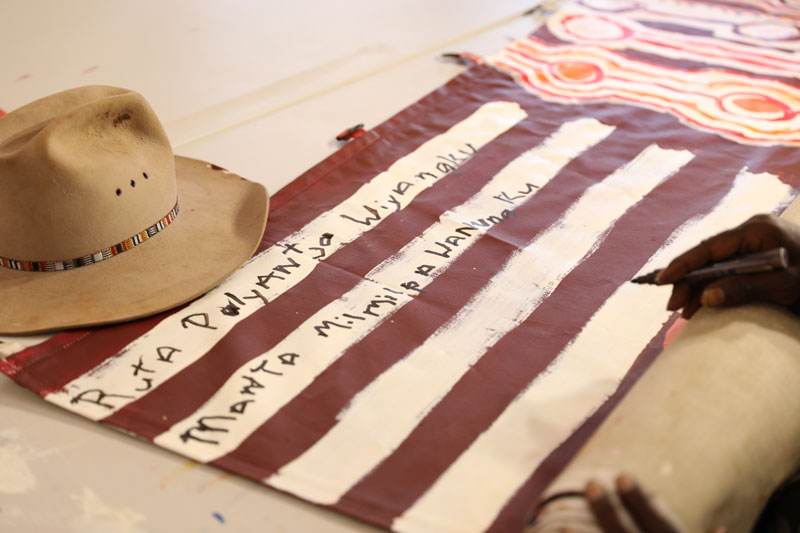

He recalls the inspiration to him as a young man watching senior people win back the rights to their own land. The book goes on to give a rich account of this time in photographs and key accounts and speeches by those involved, senior Aṉangu men and women, and non-Indigenous leaders too (all men, I note). Before this comes the invaluable heart of the book, on the mission and message of Kunmanara’s paintings, including his collaboration with spear-maker Sammy Dodd, who continues to make kulata every day, teaching young fellas the same way he learned: “Sitting and watching, listening to the stories, slowly.”

Many of his now renowned paintings, incorporating the map of Australia as a central, politically charged motif, are reproduced, together with translations of his painted texts, challenging contemporary complacencies about development impacting the land, from nuclear waste dumps to mining broadly, as well as activities like road-making, that can make “a mess of the land” when traditional owners’ views aren’t sought and taken heed of. He scorns government authorities and mining companies: “They’ve got no shame … They’ve got their eyes and ears closed.”

For this record alone of his unique manifesto Kulinmaya! would be worthwhile. But it is also a fascinating account of a life well-lived, a hymn of praise to the culture that nourished it, a testimony to one man’s vision and resolve. The book ends with Kunmanara telling a traditional story of how fire was stolen by the Bush Turkey and how Zebra Finch men got it back. As ever, he is alert to the story’s metaphoric power: “This is how we would like our message to reach the world, to spread like fire burning across the land, wouldn’t that be wonderful. Without fire, we are cold and miserable. Without our Tjukurpa we are weak and powerless.”

And just in case anyone misses the political significance of this, he spells it out. The land was stolen, and then, through the Land Rights Act, it came back to its rightful owners: “However, we all know that our land can be stolen away from us in an instant, just like the fire was stolen. So those of us that were there to receive our land back, keep holding onto it as strongly as we can, and we are documenting it so that our children can read and learn their own history. This is a good thing.”

The book features many photographs of Kunmanara. Apart from those of him and his family in childhood, a particular favourite of mine is of him with other artists in front of the Kulata Tjuta installation at Tarnanthi in 2017 by photographer Rhett Hammerton; and another with Sammy Dodd in front of Dodd’s truck, both holding kulata, by Jackson Lee. At this time, Kunmanara’s wife prefers to keep his image off the internet, so none are reproduced here.