Paintings, poles and installations from Yirrkala feature brilliantly as part of the third edition of the Tarnanthi Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art in Adelaide. With its mastery of new technologies and materials and close attention to aesthetic detail across both traditional and new media, the Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre on the far edge of Arnhem Land has become the Berlin of the Australian artworld noted for its conceptual edge, cultural sophistication and “bling” factor that makes it the Gucci of Indigenous Australian art. Not unlike Warhol’s factory, with its shimmering white ochre of mass-produced beauty, this business has serious reach.

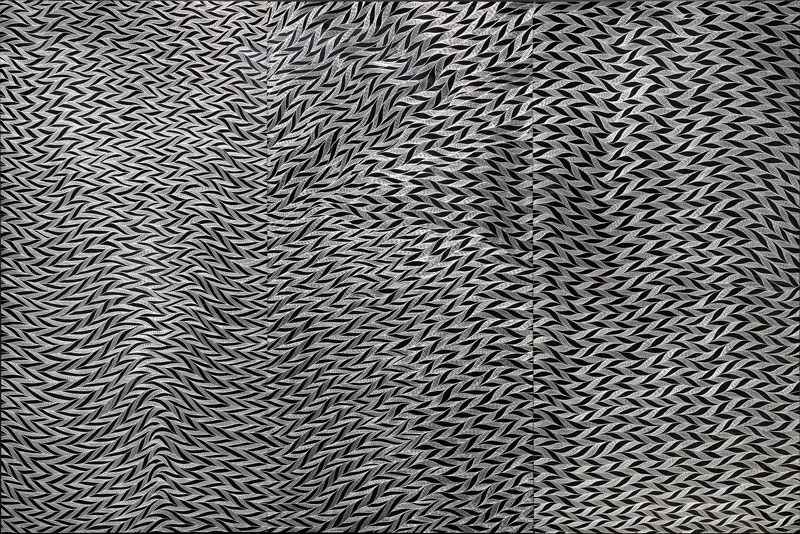

In the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA) room upon room of their bark, board and poles are painted with the wet worlds of birds and fish. Once framed by the size of the trees from which bark sheets and poles were taken, today their designs are painted, etched and laser cut onto paper, aluminium and rubbish from the nearby bauxite mine. New media is part of Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka’s armoury too, with the interactive projections of tiny fish swimming around our feet and the giant white poles of Wukun Waṉambi’s Djalkiri (2019).

With their forests, lagoons and rocky seashores, these Yolŋu artists fly in the face of the typically conceptual and critical tendencies of contemporary art. Instead they celebrate the naturalism of the landscape, re‑centring the world in a relationship with their country’s abundance and beauty. In this, the Yirrkala work parallels another Tarnanthi exhibition, Jonathan Jones’s Bunha‑bunhanga: Aboriginal Agriculture in the South‑East. The title of the show comes from the Wiradjuri word for abundance, and the exhibition is full of nineteenth-century paintings that illuminate Aboriginal agriculture and pastoralism, as well as wooden shovels and stone picks of Aboriginal making. Abundance also offers a way of interpreting the proliferation of Yolŋu aesthetics, as it offers us a glimpse into what this fertile continent has to offer, if only we take the time to look and learn from the landscape.

Photos: Saul Steed

A second interpretation of this renaissance of Yolŋu art might lie in its contemporaneity, its “post‑medium condition” or “transcategorical character”. This describes the shift in scale and material of Arnhem Land aesthetics since the nineteenth century, from rock faces and bodies to bark and aluminium. The concept of the contemporary as a crossing of media captures something of the other work in the exhibition at AGSA, such as Darrell Sibosado’s corten steel sculptures modelled on Riji (pearl shell) designs, that he imagines as public sculptures, rusting into the urban fabric as totems of saltwater life.[1] Other shifts are less visible to those outside the Indigenous domain. Pauline Sunfly’s new paintings are of her father’s Dreamings, rather than her mother’s, in a gender shift that has been all too radical for some of the Western Desert traditionalists.[2] Badger Bates is a traditional carver of boomerangs and nulla nullas, and here we see etchings that he says continue his classical practice, as inscribing a boomerang is not so different from inscribing a metal plate.[3]

These exhibitions are all to be found at the AGSA, where much of Tarnanthi is situated, while Tandanya across town hosts the hustle of the Tarnanthi Art Fair. Here beautiful bathi mul, black dyed baskets from Milingimbi, sit amidst the piles of desert paintings. The bathi mul are glorious, shimmering things apparently made with a recipe that is of the artist’s own invention, although nothing is ever entirely new in the Indigenous domain. It might be more precise to say that Margaret Rarru and Helen Ganalmirriwu have revived this type of dye from the deep history of Milingimbi, from tens of thousands of years of shifting practices. Here we see the paradox of thinking of Aboriginal art as contemporary, since it is both new and ultimately very old, innovative while being conceptually bound to the country from which it comes.

For its critics the remote Aboriginal art movement plays into the fantasies of its colonisers. Aboriginal people are only pleasing the white fantasy of an Indigenous harmony with nature with their pre‑industrial, primitivist bark paintings and baskets.[4]The accusation underestimates the sophistication of the strategies at work in places like Milingimbi and Yirrkala, that set out to displace the ontologies of white Australia with the complexity of Garrawurra and Yolŋu relations. While these Arnhem Land artists play to beauty, intricacy and scale, elsewhere Aboriginal artists employ naivety as a way of opening up conversations about the ancient and the recent, of bringing something unseen into the seen.

At the State Library of South Australia, an array of paintings of monsters and the arrival of whitefellas were inspired by the return of Warumungu recordings of elders made fifty years ago. These recordings were installed to play in a tent in Tennant Creek, where they came to life for Warumungu speakers who sat and listened to them for days at a time, before painting and re‑telling the stories in twenty‑first century English. Here as elsewhere the transcategorical nature of Indigenous art extends across time and communities.

An installation by Ngkwarlerlaneme carver Kwementyay (Wally) Clarke Pwerle also illustrates the point. Early Days (2005) sculpts a fight between spear‑wielding Aboriginal men and white policemen. The warriors are painted for war, looking properly fierce, and one of the police has taken a spear to the leg, a hole faithfully carved into flesh.

This kind of naïve brilliance would have been almost impossible for state galleries to exhibit some years ago, as remote artists, collectors, art centres and superannuation funds flocked around a commercial boom in painting. This expansive phase of Aboriginal art coincided with the globalisation of the Australian economy only to crash in the late 2000s, clearing out much of the mid- to upper-level market. The effect has been to allow a diversification of Aboriginal media, to allow artists room to adapt their work to new technologies and old. As one of the founders of the Utopia carving movement, Pwerle was carving before the collapse, but his work anticipated the revival of interest in media that isn’t painting. His is a naïve style of carving, in the sense of being unschooled by a professional art education. Instead Pwerle learned on the job, making boomerangs and shields before turning to ceremonial, historical and sporting figures.

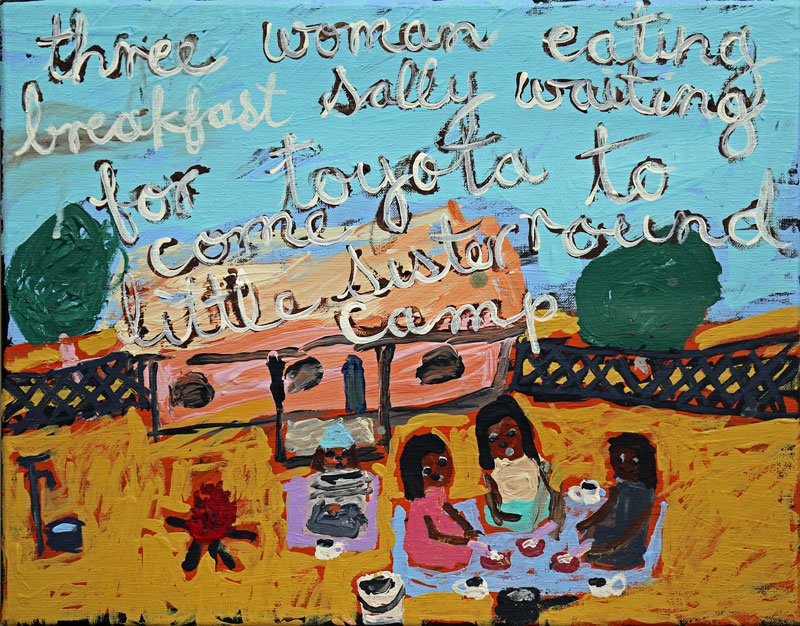

Canonical artists like Pablo Picasso and Sidney Nolan spent their lives trying to achieve this kind of naïve quality, to unlearn that which they had learned about drawing and painting. They wanted to strip away all the pretence of classicism. Many of the figurative artists of the Western and Central Deserts achieve this with ease, as they turn away from dots and circles to make realist pictures of history and everyday life. Sally M. Nangala Mulda’s paintings document the domestic dramas of the town camps of Alice Springs. She has also animated one of her stories, in No Trouble Here (2019) showing a row of children sleeping outside in the heat while two old ladies cook meat on the fire. There is nothing to see here, they tell the passing police, nothing but kids and ladies resting until tomorrow.

There is a latent power to the iconography of Mulda’s work, as her children, police and women barely move across the screen, but play out the theatre of a colonialism suspended in time. The traffic between state power and the town camps is complex and its lines unclear, as Mulda’s paintings also telling of the ongoing effects of alcohol and pre‑paid electricity cards on camp life. There are other brilliantly naive animations here too, such as Peggy Griffiths‑Madij’s Woolangem Balaj Gida – At First Sight (2019). This long‑time ochre painter animates her mother hiding from a white man in a lagoon. These kinds of stories are, in curator Clothilde Bullen’s words, made through “love in action,” playing upon “quiet resistance,” and “sharing the weight of colonial histories together.”[5]

There may be no better example of the politics of this new figuration from remote Australia than in the portraits of Nyaparu (William) Gardiner. Born into the Pilbara strike of 1946, Gardiner left the poverty of the strike camps to work with cattle and horses across the north‑west. His portraits of strikers and stockmen, people cooking in their camps and people who have passed away, come to us some fifty years after their time, and yet it is as if we can plainly see the experience of the earth etched upon their faces. Gardiner’s genius lies in the way he draws with the paint, leaning the world to the side as if the earth itself is about to tip away.

This is the kind of Australian portraiture that Sidney Nolan attempted but never quite achieved, because he never resolved the tension between figure and ground. Nor did Nolan push beyond the mythographies of 1950s Australia, as he retold stories of bushrangers and explorers. Gardiner’s Drover (2015), Yandying Family (2015) and Old Fella (2018) instead picture itinerant labourers, perfect ciphers for the vast anonymity of the country itself, into which they are drawn to be a part of the flatness of the picture.

Tarnanthi’s expansive scope lies in exhibiting the shifts taking place in remote Aboriginal art, as well as in the sheer number of artists and partner venues across South Australia. You can feel the stamp of artistic director Nici Cumpston’s inclusive largesse of vision in accommodating every type of community or project, respectful of the many different working worlds and community expectations. These include (with their price tags) more work from Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka at Hugo Michell Gallery, Gunybi Ganambarr, Regina Pilawuk Wilson and others honing serial production and object design at the Jam Factory and lightworks by Koskela homewares at SASA Gallery (University of South Australia). There is a focus on activism at ACE Open (working with Ceduna and Ku Arts) on No Black Seas, campaigning against drilling for oil in the Great Australian Bight (with shades of Redback Graphix), Ryan Presley’s Blood Money, an exchange booth that viewers can’t avoid on approach through the AGSA back entrance, and the more interrogative Unbound Collective occupying and interjecting with the colonial site‑specificity of the buildings that now serve as Adelaide’s Migration Museum.

It nevertheless feels like the heartland of Tarnanthi, and the dominant exhibition premise of the AGSA galleries is the focus on remote rather than urban artists, not so driven by the more academic discourses that preoccupy the museum world. The vested interests here lie in the deep time represented in the Mulka Project’s digital mind‑map, The Gurrutu Engine, produced by Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka’s digital arts studio; perhaps too algorithmic for the general punters walking through the galleries to usefully comprehend. Another audio‑visual work made in‑house at Yirrkala is by the deaf Gutingarra Yunupingu who signs to us in Yolŋu. Combining two languages, with which most of the viewing public are unfamiliar, Yunupingu performs an insider’s view of this deep time universe.

Much is at stake in the meeting of so many different minds and cultures representing the expressions and interests of Aboriginal Australia. In scale, Tarnanthi now eclipses other Aboriginal art events, such as the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair, Desert Mob in Alice Springs and Darwin’s National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards. The scale was reflected in the extraordinary program of invited artists that launched the exhibition, the opening more like a meeting of the clans, featuring Yolŋu, Tiwi and Kaurna dancers, followed by Djambawa Marawili and Baker Boy at the podium, in front of an audience on Adelaide’s North Terrace that was at the capacity of the sports stadium across the river. Adelaide is clearly at a turning point, embracing a momentum through the proposals for an Aboriginal arts and cultures gallery, with Federal investment of $85 million announced in March, to occupy the former site of the old Adelaide Hospital.

This investment in Aboriginal art also recalls the glory days of the South Australian Museum, that until the middle of the twentieth century vacuumed up the paraphernalia of Aboriginal Australia. It is also with Tarnanthi in mind, loaded with its support for the art market, that it is possible to revisit the crisis of confidence that came after the market downturn of the 2000s. It may be no coincidence that this crisis coincided with then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations, the promise of a new beginning for race relations followed all too quickly by the curt dismissal of the Uluru Statement by a subsequent government. Amidst this failure of the imagination, Aboriginal art remains a powerful voice of dissent.

As long as Aboriginal politics remains on the sidelines of Federal Government concern, this art movement will remain charged with the politics of representation and recognition. It is impossible not to see Tarnanthi as a devastating reminder of the diversity and dynamism of Aboriginal history. The brilliance of Sibosado’s giant Riji designs or Gunybi Ganambarr’s Darra (2019), a shining aluminium wall of waterweed patterning, are seen here as totems of an Australia to come. The ambition of artists from remote Australia is no longer to simply represent their countries, but to create the iconography of a reimagined Australia. That this ambition belongs to an Australia imagined from below, rather than from above, makes it all the more remarkable as an achievement.

Kerry Stokes Collection, Perth. Photo: Saul Steed

Footnotes

- ^ Darrell Sibosado, Artist Talks, Art Gallery of South Australia, 18 October 2019.

- ^ See John Carty, Creating Country: Abstraction, Economics and the Social Life of Style in Balgo Art, PhD thesis, Australian National University, 2011, pp. 332–34.

- ^ Badger Bates, Artist Talks, Art Gallery of South Australia, 19 October 2019.

- ^ See, for example, Vernon ah Kee in Robert Leonard, “Vernon Ah Kee: Rainforest Surfer,” Art & Australia 45.4, 2008, pp. 640–45.

- ^ Clothilde Bullen, Artist Talks, Art Gallery of South Australia, 18 October 2019.