.jpg)

In the twenty years since Donald Brook wrote about “Deschooling” in a thematic focus on art education in the 1999 edition of Artlink, The Future of Art (19:2) art education as this “most depressing non-subject in the entire catalogue of non-subjects” has come full circle to embrace a more “world-centred” approach, as Gert Biesta advocates in his feature essay for the current edition. This approach, embracing not just art education but also the pedagogical turn in art practice as participation in knowledge-making and knowledge‑dissemination, is taken up boldly across this issue informing the cross‑curricular objectives of educators, artists and curators working in the world today.

The late Donald Brook, who wrote prolifically and compellingly on art education, frequently for this magazine, was at the forefront of proposing radical solutions to what he saw as self‑evident problems across both the secondary school and tertiary art education sectors (including rigorously reconfiguring art in schools to something called “representation”, or closing them down). In this edition, Alasdair Foster takes up the mantra of Brook’s uncompromising stance to question the purpose of art education, and our preconceptions about what art is and what constitutes the appropriate entry into the profession in his provocatively titled essay “Vanishing into action: Art beyond the contemporary.”

These debates have continued to churn since the 1990s, when art schools entered the faculties of universities, supporting the emergence of practice-based research. The intersections of knowledge made possible by interdisciplinary training, and the changing models for art education as sites of immersion in creative becoming, are further discussed by Una Rey in her essay surveying the current institutional offerings as training grounds for entry into the cultural industries. These ideas are also taken up by Tara McDowell in reflection on new methodologies and the possibilities of cognitive and affective practices in curatorial research, drawing on her experience of setting up Australia’s first Curatorial Practice PhD at Monash University.

When we proposed this edition on art education to Artlink last year, we had already been researching and working in the field of art education with a particular interest in public pedagogies and alternative models that bridged the gap between the classroom, the gallery and the studio, empowering a greater engagement in contemporary art through new teaching practices in schools. Rather than ruminating on the past or speculating on institutional futures, we envisaged a focus on the clustering of debates that reflect the fluctuating drivers positioning art education in particular ways right now.

Just as education in general is shifting, with the rise to open and often free access to information and learning, we wanted to consider the new practices and methodologies and the ethical responsibilities surrounding public pedagogies, in response to the demands of a community of stakeholders that often begin with those first encounters with art that happen in school. The role of the artist as the teacher, or the teacher as the artist is championed by Henry Ward in an essay in praise of teachers who work alongside their pupils to bring “their own work and ideas into the classroom, flatten out the perceived hierarchies and establish an environment that enabled everyone to be making, everyone to be thinking, and everyone to be learning in response to the spaces they inhabit.”

.jpg)

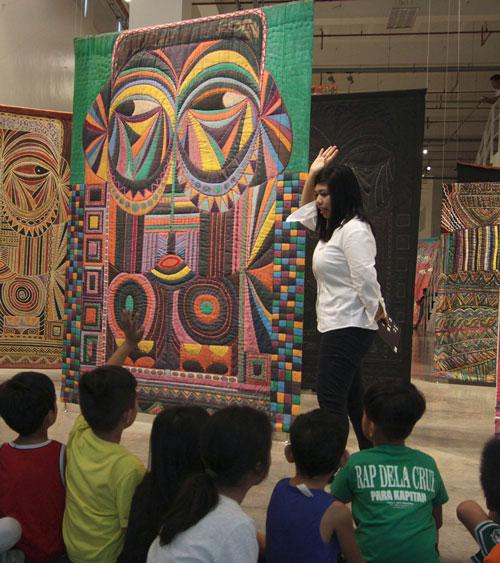

Initiatives that mobilise participation in art as knowledge-making, or knowledge sharing through responsive public programming in the gallery or museum are given especial impetus in the focus on two cultural institutions from Southeast Asia, with Josalina Cruz and Paula Acuin writing on audience-development initiatives for the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MCAD) in Manila and Aaron Seeto on the activities of the Jakarta‑based Museum MACAN. Where museum education is sometimes thought to be secondary to the “real” work of collections and curation, these examples blur the divisions to centralise their educational remit by responding to social concerns and engaging their communities in educative practices.

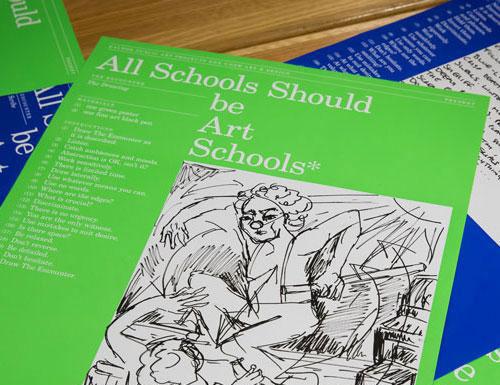

Two art education-focused events in Australia serendipitously occurred as we planned this issue and helped shape its contents. In October last year, Kaldor Public Art Projects in conjunction with UNSW Art and Design held an educators’ symposium in Sydney titled “All Schools Should Be Art Schools” after the slogan coined by British artist Patrick Brill (Bob and Roberta Smith). As part of the proceedings, artist Agatha Gothe-Snape produced whiteboard-style wall texts summarising and framing ideas presented by speakers at the event, an example of which the artist is seen to be hammering away at on the cover of this issue, which is further elaborated upon within. These works function as a visual map of the mercurial debates around art education, purporting to synthesise the key concepts while requiring the viewer (the reader) to fill in the gaps.

.jpg)

Then, earlier this year, the exhibition Shapes of Knowledge opened at Monash University Museum of Art. This exhibition, with its overarching conceptual premise inspired by the growing international discourse around pedagogy and contemporary art, included an extensive public program of performances and workshops that mobilised teaching and learning experiences beyond the gallery and the university itself to also work with the staff and students of the Dandenong Primary School, among many of its project offshoots. In our interview published here, we spoke with Hannah Mathews and one of the participating artists, Alex Martinis Roe, about the types of knowledge that can be gained from art, teaching through art and artmaking to inform the production of knowledge.

In his book Letting Art Teach (2017), Biesta argued for education as an encounter between subjects culminating in a turn towards the world, citing Beuys’s famous performance How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965) as an example of such a turn. Applied to art education, this works as a practice that is not concerned with the expression of self, but with the creation of self in relation to the world, advancing the potential of the artist/student/teacher into realms that sit uncomfortably within current educational curricular constraints to instead offer the potential of new creative methodologies so desperately required in these uneasy times.

Art education is a multifaceted theme. The essays we’ve collected in this issue are pluralistic in their views and approaches, highlighting the current surge in awareness of this all-important embrace of the pedagogical turn, and the ever-evolving capacity for students, teachers and artists to make strategic interventions in art as in life.