The controversial and flamboyant British film director Ken Russell is alleged to have said that in his youth he harboured a wish to become a ballet dancer, based on his ability to leap gracefully and with presence. These aspirations reminded me of my first encounter with Travis de Vries at an end-of-year NAISDA performance, in which he spun across the space, finishing with an amazingly accomplished leap. Just as Russell gave up on becoming physically airborne, but achieved acclaim in photography and film, Travis de Vries, a Gamilleroi man born in Mussellbrook, derives his wellspring from a myriad of cultural influences, including his Western European ancestry (Scottish, another colonised clan society).

Aboriginal people are everywhere, and Aboriginal people do everything. Working in regional and capital centres, de Vries has had a successful and wide-ranging career as a performer, working across different art forms, styles and locations. These broad experiences and a determination towards expression aimed at diverse audiences appears in his current art work. As highlighted by the title of this ambitious solo exhibition of over forty works exhibited at Gallery Lane Cove on Sydney’s lower north shore, The Garden is a transformative and regenerative inroad into the land and landscape, a vehicle to transcend human loneliness and alienation (as captured in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden), also an internalised place of spiritual growth according to the Christian metaphor (as in Jane G. Meyer’s The Hidden Garden).

Gallery Manager and Curator Rachel Kiang has used this generous space in deep suburbia to mount several exhibitions of Aboriginal artists, including Jason Wing’s group show Black Mirror in 2018, to tempt local audiences with interesting new art. There is the Aboriginal story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, that version of the story where Eve would have ignored the apple and eaten the snake. This “Hidden Garden” is also the world of Australia’s pre-contact with Europeans, which allowed Aboriginal people to survive and thrive for over 50,00 years in the paradise described by Bruce Pascoe in Dark Emu (2014).

The Australian land–garden with its wide deserts, could have been regarded as a Biblical Disneyland by the first European colonists. Many white Australian artists have attempted to rework the Australia landscape in Biblical terms and many other international artists come here to obtain such a revelation, or absolution, sometimes including Aboriginal imagery. These landscapes of post-apocalyptic, “burnt-out” country – burnt-out people, burnt-out land, devoid of hope – stereotypically imagine hell on earth.

The art arrayed here, with its own unique psychogeography, is an outcome of the 2018 NSW Indigenous Artist Fellowship awarded to de Vries. His narrative interweaves and reworks the classic Christian Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and their Expulsion with Aboriginal overtones. An awareness of space from his dance times is used here too. The exhibition fills the large gallery space, for which he has created numerous small garden beds with living plants, placed between his graphic art works. Possibly, like the reference to growth in clusters, these works of art might have benefited from a tighter condensation (also in the arrangement of the smaller works), but the imagery is compelling.

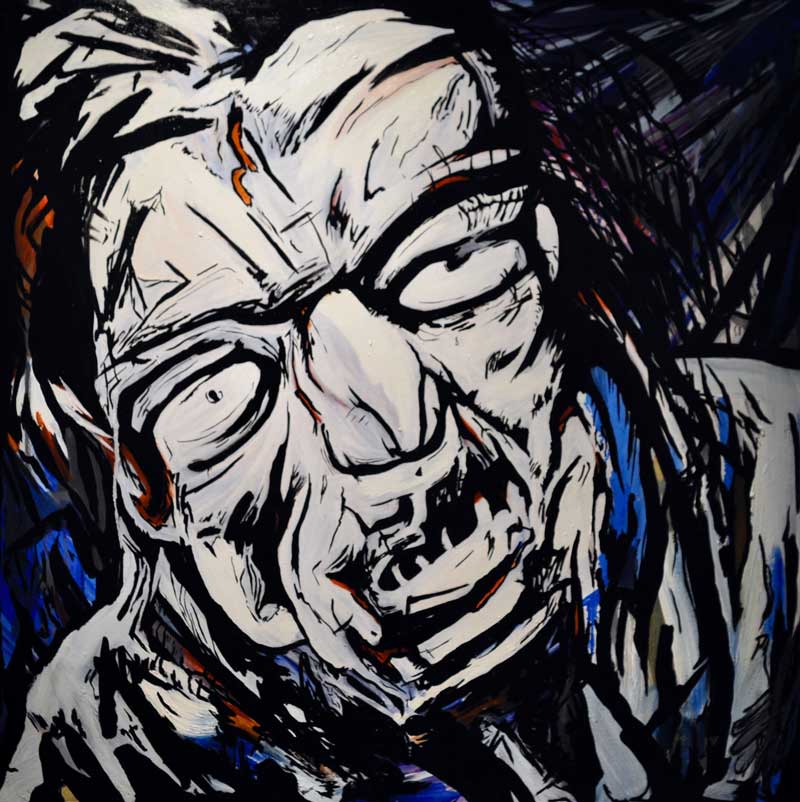

In their expansive totality across a number of forms, De Vries employs photography, charcoal mark-making on paper, 3D stick and found object constructions, animal skulls, video and audio-scape, dominating Manga-style images of faces – eyes watching, immersing the viewer. Arrangements of sticks into triangular structures create architectural organisations of tension and balance. Human-sized spirit beings with bird skeleton skulls lurk here and there. Birds are totemic creatures – messengers of death, birth and arrival, and of symposia conversations. An impasto naked female figure painting talks of “Eve’s liberation on expulsion” as the artist explains.

In Aboriginal society an individual learns to become physically, emotionally, and economically independent, and yet ambiguously gregarious, holding onto the need to be social. Adam and Eve were purportedly the mother and father of all humans in Christian belief, a time when human consciousness broached pure animal instinct. In Aboriginal beliefs, the first people come from several anthropomorphic beings: a man and two (or more) women, and they create their own garden as they traverse and revel in it.

The awareness and naming of the natural order represents a similar human consciousness. In this body of work, Travis suggests “Colonisation” threw them (us) out of Eden. The Australian continent, filled with an enormous list of poisonous snakes, spiders and other deadly creatures – deadly, that is, to modern Western society – is not nearly as deadly as European Colonisation, which made this Garden of Eden far more dangerous than any of the aforementioned creatures.