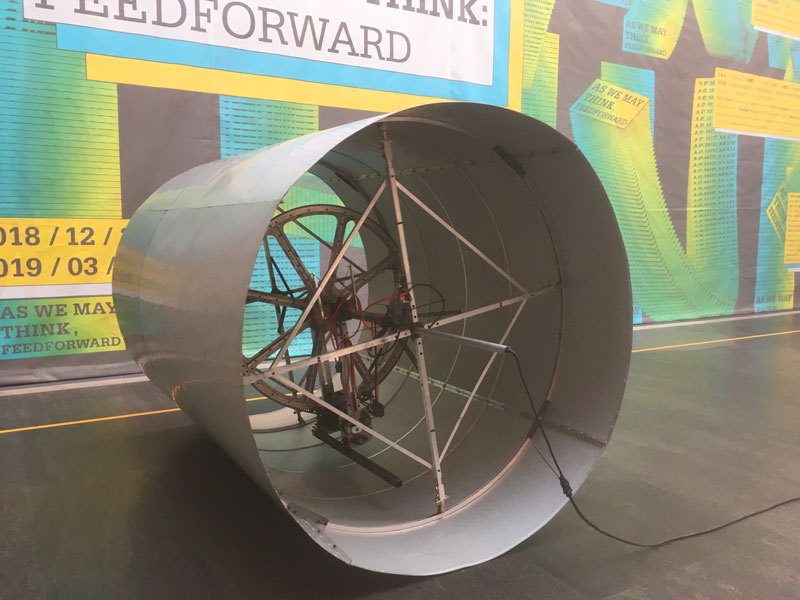

Just twenty years ago the sprawling city of Guangzhou was largely a mangrove swamp. Since then the Pearl River Delta, including Hong Kong, Shengzhen and Guangzhou, has become a maze of roads and towers built over its snaking waterways. More than half a billion people live in the Delta now, its population expanding faster than anywhere else on the planet. It makes sense that the 6th Guangzhou Triennial is focussing on a kind of futurism with its theme, “As We May Think: Feedforward.” Its heady mix of three curated components, the biological, digital and machinic, addressed the capacity of the species to transform the world and itself, resonating with China’s vast futurist experiment taking place just outside the museum walls.

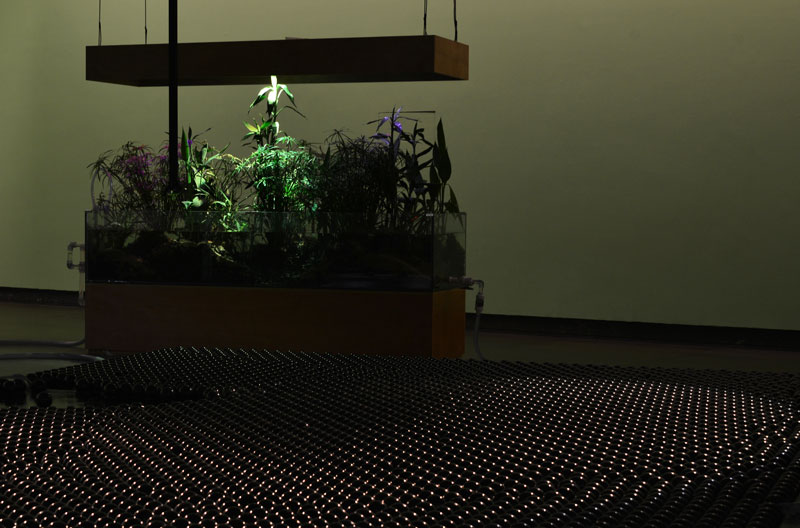

Most of the big, ambitious installations here draw on scientific architectures of different kinds. One of three expatriate or nomadic Australians on show is Tega Brain. Now living in New York, Brain draws upon her engineering degree to program the lighting and watering conditions for two swampy terrariums. The wetland simulations of Deep Swamp (2018) take place with two computers out of sight, as if we can only appreciate nature at one remove, from a misty distance. The computers compete to model their waterworlds after downloaded amalgams of pictures, nature coming after artifice rather than the other way around. Deep Swamp is installed next to a complex of steampunk style tubes that feed Gilberto Esparza’s Autophotosynthetic Plants (2013–14) that will never see the sun, sustained in vitro by artificial lights. Again, artifice has eclipsed nature, the energy of the human world exceeding that of the sun and soil.

Shen Ruijun’s Shoal (2016) is the exception to this tendency to bio-spectacle. Instead of going big she makes a tiny glass tank into which we peer to see a strange animation of bird and insect shadows moving amidst an obscure tangle of vegetation. It is as if this local artist, old enough to remember the mangroves that once extended across the landscape, can recall nature and its creatures only in a shadowy dream. Shoal was curated into the machinic component of the show (or in curator-speak, “Machines Are Not Alone”), but could have equally sat within the biological “Evolutions of Kin” or digital “Inside the Stack”. This trilogy of curatorial futurisms is most successful, and the exhibition most coherent, where the works blur the themes, as if the curators were thinking of each other's ideas when choosing their artists.

This blurred sense of possibility is certainly part of the curatorial message of the show, as the convergence of technologies works to create a regime of artifice. The problem for artists speculating on artificial and natural systems is that it is difficult to be as impressive as a world generating new systems with incredible speed. Such new systems are generated by confluences of well-resourced corporate, state and technological interests. One only needs to travel through the Pearl River Delta to be dazzled by the possibilities of convergent technologies. Shengzhen, down the river from Guangzhou, is the world capital of reverse engineering, a manufacturing hub that specialises in making just about anything to order, and in shipping it to the rest of the world. In Australia there is a good living to be made from knowing which company does what, and how to best get a container of specially made, plastic wrapped product into the country. Speculative art is hard pressed to compete with such a capitalist fantasy, and dates quickly next to the imagination of the better marketing think-tanks.

Marie Caye and Arvid Jense are two artists attempting to compete with this dazzling world of smart stuff. They went shopping for cheap and clever Chinese technology to make a coin-operated vending machine that has a mind of its own. Based on previous versions of SAM that employed their own accountant and maintenance staff, SAM3 (2018) proved a problem for the Triennial customer. Having made enough money to pay for its own power, it refused to dispense drinks. Here the audacity of technological progress tips into abrasiveness, and a sense that humans don’t deserve the technology that they make. Equipped with its own simulated intellect, the drinks dispenser insists that it is more than its own banal place in the world, more than a part of this landscape of novelty.

What is fascinating about SAM3 as with much of the work in this show is just how artists have made things work. Bootstrapped drinks machines, digital terrariums and, as we shall see, a protoplasm generator testify to the do-it-yourself dimension of the convergence of the digital, mechanical and biological. The tension of these artworks lies in the way that they propose nature without a natural world, preserving the outlines of what we once called nature while being sure that we can see its artifice. And while the art here might appear to be the kind of cutting edge work we have come to expect from new media, its collision of nature with technology, of anachronism and futurism, has long been the subject of older mediums from Chinese calligraphy to European painting.

It is worth returning to an older mode of thinking about art to grasp the point. For while the catalogue for this exhibition is packed with new ways of comprehending these technological transformations, the artworks remain tied to the banality of being objects among other objects. The indifference of SAM3 embodies a more general condition of indifference that permeates a technologically saturated world, the wearying effect of having so many devices, so many opportunities to interact with the inanimate. The effect is not necessarily a new one. T.J. Clark writes of Cezanne’s pictures of more than a hundred years and several generations ago, that “his painting can make a connection between geometry and history; but only because he is at the same time so confident that he can keep the two utterly separate, incongruent. Facts of making are different from facts of understanding …”[1] And this is precisely the kind of incongruity that SAM3 represents: a thoroughly boring drinks dispenser is infused with the enigma of its refusal to dispense through insistence on an interiority that haunts its own making.

The challenge for artists is not to succumb to the novelty of making things work, but also to preserve something of the historical tensions in the singularity that once described the autonomy of computers and other machines to determine their own fate. Artists are no longer expected to imagine this future because it has already arrived. Instead, they are growing, mechanising and programming its possibilities. Making such technological processes visible, artists echo the technological Zeitgeist, the ways in which Facebook and Google (and in China, Baidu and TenCent) have automated their own interests. So it is that one of several works censored from the Guangzhou Triennale was a version of the Microsoft chatbot Tay, originally shut down after users taught it to say messed up things about “rape, racism, domestic violence, women’s rights and genocide” after just one day.[2] Artists Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman were first asked to remove lines where their new, artistic version of Tay spoke about Hitler and rude robot sex, before the curators were asked to take down the whole video piece, I’m here to learn so :)))))) (2017). The New York Times suggested that theworks were censored because of the show's “hard-hitting questions about ethics,” but it is likely that the reasons were more banal.[3]

As we have argued before in Artlink, censorship in China has as much to do with asserting authority as it does with keeping on top of potentially damaging social issues.[4] While it may have been Tay’s rudeness that brought the local police down on the work of Blas and Wyman, it is possible that the reason other works were censored was because of violence, gambling and the potential offence caused by the appropriation of ceremonial objects.[5] In other words, Chinese officials are more concerned about defending Chinese mores than the ethics surrounding biotechnology or artificial life. And given the variety and vagueness of such mores, it is easy to see how, as a museum official says, the works could be seen by overzealous authorities to offend “the sensibility of Guandong people.”[6] In the light of the sheer banality of this content, it is less to do with the objects being censored than the significance of the censorship itself.

While such censorship is unfamiliar in the West, it is an everyday part of life here, with a heavily redacted internet and media. In China more than anywhere else, capitalism and technology have converged with the state’s informational infrastructure. It may be that censorship here is better thought of in terms of Benjamin H. Bratton’s idea of the “stack”, a new computing megastructure that has arisen to surpass older models of power.[7] This is one of the concepts the curators draw upon to theorise their choice of works, and it refers to the Alibaba, Baidu and WeChat platforms that dominate the Chinese internet. In Australia, we are instead part of the American stack of Apple, Google and Facebook. There are other stacks in Europe and Russia, too, each tied to conglomerates of language and industry, overlaying geography with clouds of information.

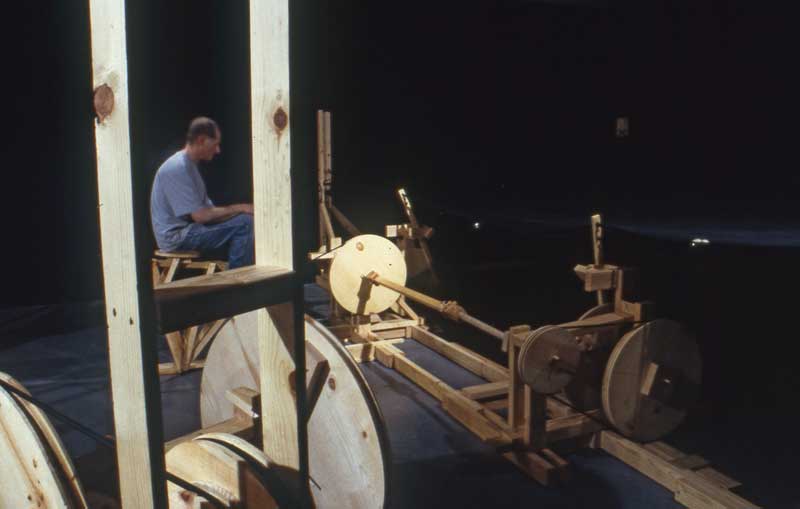

The Triennale’s themes of autonomous life and machines, of simulated nature, can be thought of as speculations upon the politics of the Chinese stack and a new industrial age. In this sense, a few actual machines of metal and wood serve as conceptual anchors to the more obtuse tanks of biology and code. Thomas Bayrle’s Rosaire (2012) is a motor that recites the rosary. Dorian Gaudin’s Missing You (2016) and Rites and Aftermath (2017) are enormous assemblages of air compressors, sheet metal, rotating cylinders and motors. In this category, the work of Californian Bernie Lubell is more hopeful than the Europeans, his interactive wooden construction Sufficient Latitude (1999–2012) simulating the experience of being on a boat at sea. These sculptures, resonating with neo-dada and systems art, could well have been dropped straight out of the 1970s, their mechanism and invention impressive on their own machinic terms.

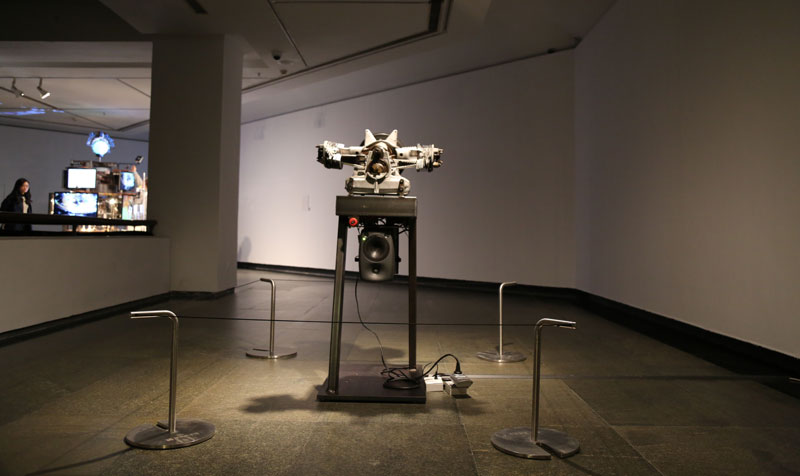

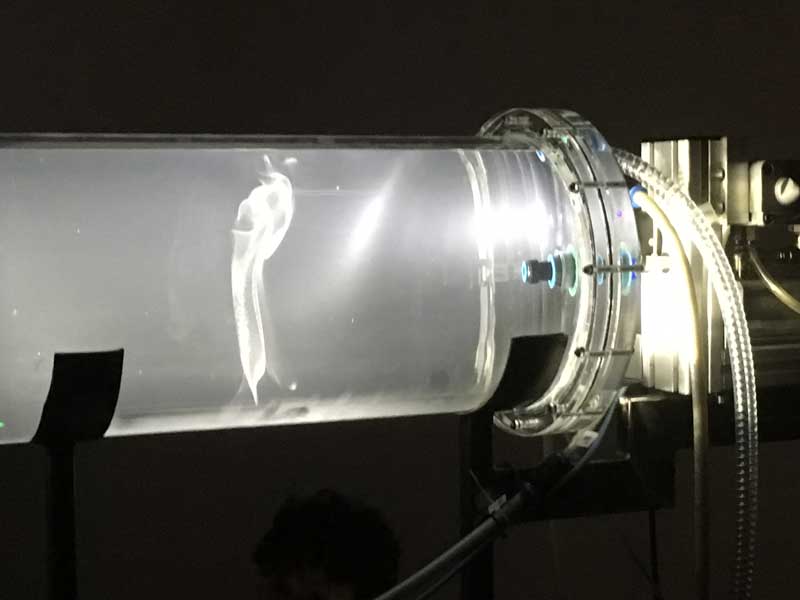

Most of the works on exhibition here required the artists to have a good grip on computing power to create their conceptual and actual architectures. Here, Herwig Weiser’s Summoned Disambiguation(2013–18) stands enigmatically for the capacity of processing and machinic power to work together. A protoplasm moves along a long, transparent tube, emerging from a tangle of wires as if some virtual entity is pushing its way out into the actual world. Installed in a darkened room it is as if we have stepped into some intimate cyberpunk film set, but the work also plays with a history of sculpture in a confusion of liquid and solid, present and absent.

It is possible, then, to glean something of the way that what was once known as new media art has been captured by the convergence of technologies and the politics of this convergence. If there is now some dissatisfaction with this older term for an art of technology, it is because the different medias themselves have now dissolved into each other and come to serve other interests. In this exhibition machines are plugged into gardens and tubes of experimental matter as a kind of artistic singularity. But early theorists of the singularity rarely included the politics of convergence in their predictions of technological totality. As computers have become central to twenty-first century lives, new regimes of power have arisen as quickly as the skyscrapers of Guangzhou. There is now little gap between speculation and actualisation, while technology has come to assume political significance. Increasingly skilled and capable of keeping up with technology, artists have turned to autonomisation as a way of critiquing the ambiguities of this politics of convergence.

Footnotes

- ^ T.J. Clark, “At the Courtald,” London Review of Books, vol. 32, no. 23 (2 December, 2010), p. 22.

- ^ These words are taken from Blas and Wyman’s I’m here to learn so:)))))) (2017).

- ^ Amy Qin, “Their Art Raised Questions About Technology. Chinese Censors Had Their Own Answer,” New York Times,14 December 2018: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/14/arts/china-art-censorship.html.

- ^ Darren Jorgensen and Tami Xiang, Inhuman Flow: Censorship and art in the two Chinas," Artlink, 38.3, September 2018, pp. 18–31: https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4700/inhuman-flow-censorship-and-art-in-the-two-chinas/

- ^ The violence was in two Harun Farocki videos from the Parallelseries (2012–14), Parallel III and IV, while I and II remain on show. Lawrence Lek's Geomancer(2017) shows gambling machines banned in mainland China, and a pair of paper shoes were taken from an installation by McGuffin magazine and Alexandre Humbert, The Life of Things – Wedding of Objects(2017–18).

- ^ Huang Yaqun, deputy director of academic affairs at the Guangdong Museum of Art, quoted in Qin.

- ^ Benjamin H. Bratton, “On Hemispherical Stacks: Notes on Multipolar Geopolitics and Planetary-Scale Computation” in As We May Think: Feedforward: The 6th Guangzhou Triennial, (ed.) Wang Shaoqiang, exhibition catalogue, Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, 2018, pp. 77–85 at p. 80.