It seems obvious to state that Jude Adams’ retrospective, Narratives from the Family Album, is at home in the domestic setting of artroom5, the suburban house-gallery of curator Vivonne Thwaites. But the activation of the home-space is, like the work itself, subversive. Beyond the tidy front garden the house opens up to reveal inventive, revolutionary works hanging on the familiar walls of everyday living spaces. This could be a metaphor for what was happening in mothers’ lives and homes in the 1970s when Adams was documenting the struggle to reconcile her mothering roles with an art practice. Today mothers continue to labour in mother-space, loving, caring, keeping and letting go. Thanks to pioneer feminist artists like Adams, this works continues to engage in a broader public discourse, as represented in the opening remarks of Catriona Moore, describing Adam’s work as “a viral practice that takes place in the kitchen and the bedroom, in the studio, in the gallery, in the seminar room, on the streets …”

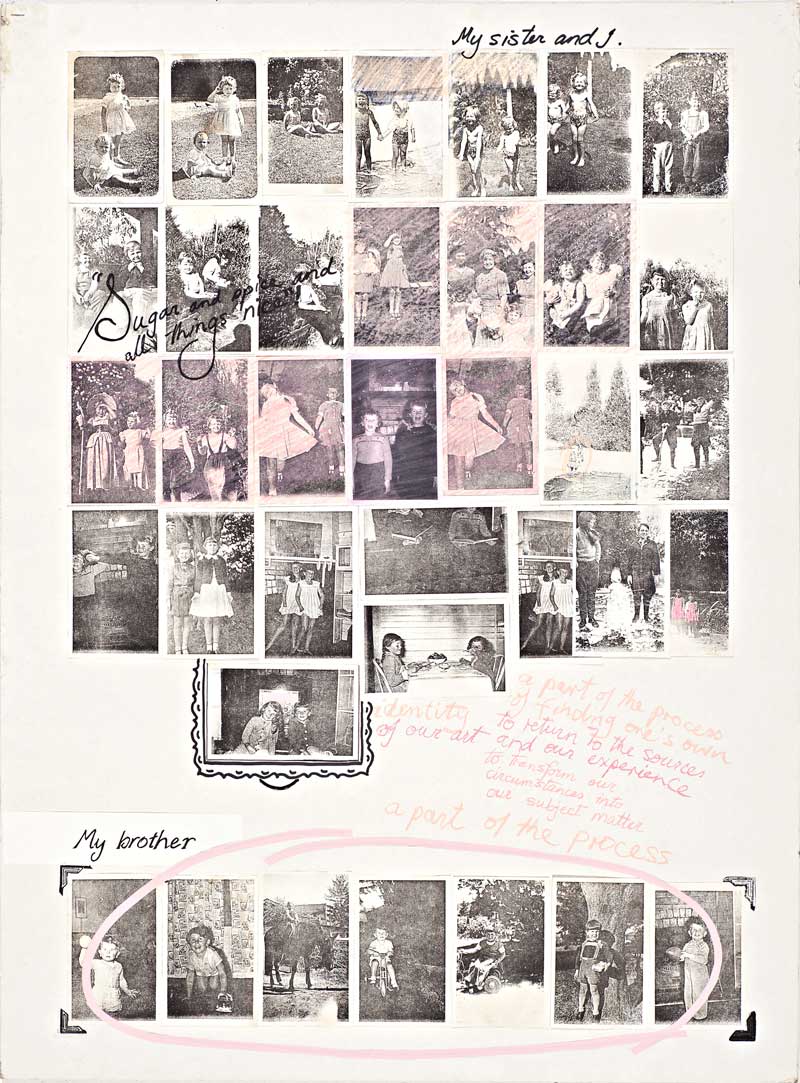

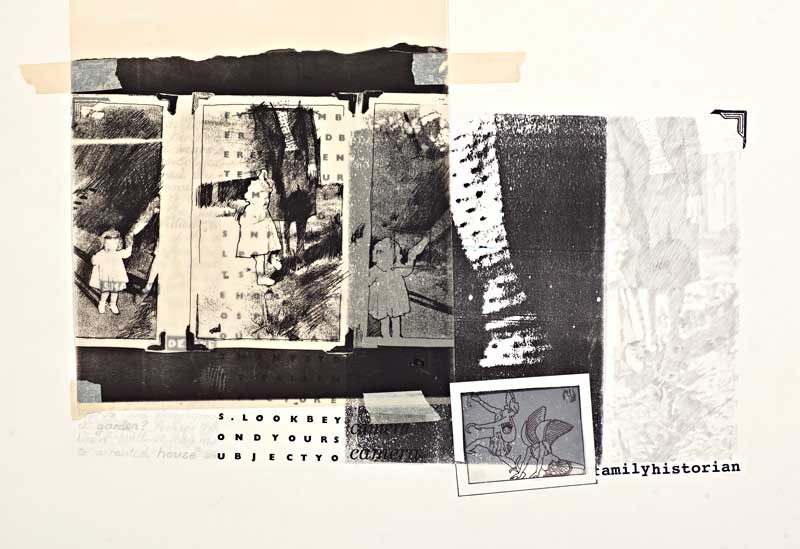

Much has changed since Adams began to photograph and perform the maternal everyday and to use her family photographs as an archive, “exploring how media representations of femininity impacted on family photography,”[1] in works such as Self-image (Pose) (1976). This collage of photocopied family photos reorganises the album to highlight the performance of gender throughout childhood. The codification of mothers’ roles and behaviours is also explored in the series Let your camera be the family historian (1993–95 and 2018). Recovering these works now suggests the accumulative work of intergenerational feminist activism.

But much still remains unchanged. The 2018 Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey identified that there are persistent gender biases in the areas of care and domestic labour.[2] The 2018 Women’s Health Survey reports that two thirds of women feel “anxiety or on edge” nearly every day, with researchers linking this to time pressures experienced by working, caring women.[3] The Countess Report, 2016, identifies that women between the ages of 35–50 are still poorly represented in the visual arts in Australia, attributable to women taking on greater carer roles during these years.[4]

Feminism’s unfinished business is evident in the re-presentation of many of the works in Narratives from the Family Album. Works that were stored, almost lost, within Adams’ shed-studio during decades when her paid work and family life necessarily took precedence over her art-making practices, now form the archive. They “let us … remember those ‘Aha!’ moments of personal-political revelation so keenly felt, decades ago. Through them we can time-travel back to the shock of confessional female imagery and taboo materials …”[5]

Cloth nappies feature heavily in early feminist art, as both ground and support, as in works from the series Post Partum Document (1975) by Mary Kelly, and Motherwork’s Laundry Project (1977), as two well-known examples. Nappies effectively describe the physicality and repetition of maternal caring, they stand for what Simone de Beauvoir calls “the torment of Sisyphus,” the endlessly repeating tasks of maintenance work.[6] Adams’ series of framed polaroid photographs, January 8–15th 1979 (“recoding everyday action as art”) (1979), is a diaristic visual record of the rhythms of mothering, punctuated by the washing, hanging out, and taking in of cloth nappies. Adams’ diagrammatic nappy works, Three ways to fold a nappy (1979), recall Kelly’s strategies of bringing attention to the production of meaning in the maternal role.

Adams recalls the reaction from many of her peers to her focus on maternal and domestic routines was that the postmodern turn to the everyday did not include that sort of everyday, in a blatant disavowal of women’s experiences.[7] The small drawing, Private lives (Maintenance art: Pilchers) (1979), reworked 2018, quietly insists on the transformative potential of mothers’ quotidian experiences. While the text incorporated in the image reads, “Since having a child, floors and household fixtures have assumed a different significance for me … My perspective is directed downwards ….” the, sensitive, closely observed drawing indicates this downward looking is actually a contemplative, creative gaze.

While it becomes increasingly rare for parents to labour with the drudgery of cloth nappies (who even knows what pilchers are?) the work of the mother and her body in domestic space continue to be consumed and regulated in other ways. The renewed pressures of “intensive mothering,”[8] and the celebrity-driven quest for bikini-ready post-partum bodies represent a backlash against the successes of 1970s feminism, exhorting women to self-regulate.[9] Adams’ performance Landmarks (1979), shows these structures were already in place decades ago. The dress worn in the performance, hand sewn by Adams’ mother in the mid 1960s for a school formal, hangs in a corner of the exhibition as a powerful symbol of the ways women’s bodies and behaviours are defined and constructed.

Photographic documentation of Landmarks in the Women’s Art Movement magazine (Adelaide) along with the mixed media Self-image (Performance) (1976), and Self-image (Play) (1976) demonstrate Adams’ long engagement with performative ideas of gender and identity. In discussing the obstacles for women and mothers continuing art career trajectories, Adams celebrates that “Many art graduates now opt for multi-professional career paths such as artist/art writer/curator …”[10] But this could also be indicative of the growing pressures on women, not to have it all, but to do it all. In this survey of Adams’ work, mostly from the 1970s, the silence of the unrepresented intervening years is powerful in its reflection upon undervalued carework and creativity.

Footnotes

- ^ Jude Adams, “Looking from with/in: feminist art projects of the 70s,” Outskirts Online Journal, Volume 29, 2013: http://www.outskirts.arts.uwa.edu.au/volumes/volume-29/adams-jude-looking-with-in.

- ^ Roger Wilkins and Inga Lass, The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 16, Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research, University of Melbourne, 2018: https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/2839919/2018-HILDA-SR-for-web.pdf, p. 82.

- ^ Jean Hailes for Women’s Health, 2018, Women’s Health Survey 2018: Understanding health information needs and health behavior of women in Australia: https://jeanhailes.org.au/contents/documents/News/Womens-Health-Survey-Report-web.pdf, p. 4.

- ^ Elvis Richardson, 2016, The Countess Report, 2016: http://thecountessreport.com.au/The%20Countess%20Report.FINAL.pdf.

- ^ Catriona Moore, “Jude Adams, Exhibition Opening Notes,” University of Sydney, October 2018.

- ^ Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, New York: Vintage Books, 2010, p. 539.

- ^ Jude Adams in private conversation at artroom5, Henley Beach, South Australia, 3 November 2018.

- ^ Sharon Hays, The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998, p. 97.

- ^ Lynn D. O’Brien Hallstein, 2011, ‘She Gives Birth, She's Wearing a Bikini: Mobilizing the Postpregnant Celebrity Mom Body to Manage the Post–Second Wave Crisis in Femininity,’ Women's Studies in Communication, 34:2, 2011, pp. 111–38.

- ^ Jude Adams, 2013.