There’s the art, that still gets collectors queuing all day to be first inside when the doors open, and there’s the mob. Increasingly, the mob – Aboriginal artists, families, friends, artsworkers from the desert Aboriginal art centres – are making Desert Mob much more than an exhibition. It’s an assertion of cultural vitality and a place of encounter and cultural exchange, the best on the Central Australian calendar. While the exhibition remains on show for six weeks, the most dynamic part of the encounter takes place over four days, from the opening of the exhibition on Thursday, through a day-long symposium on Friday featuring the artists speaking to their work, a marketplace that follows on Saturday, and over the weekend several associated shows and events in town-based art centres and private galleries working with art centres.

In 2018 all this took place in an atmosphere of heightened political manoeuvring around a proposed national Aboriginal art gallery in Alice Springs. The Northern Territory Government has put this forward as the centrepiece of its vision for Alice Springs as the “Inland Capital”. Trouble is, after a good start, they have proceeded without Aboriginal leadership and tied the project to local economic agendas, in the process managing to alienate a lot of Aboriginal people, dumb down the vision and divide the broader local community on the issue of the gallery’s location. In this context it was salutary to see the 28th Desert Mob remain steadfast in its focus on artists, their work, their voice, and the transmission of all this between artists, down the generations and to audiences.

Rene Kulitja opened the show. She is not a big name in the art world sense, but her life in many ways encapsulates the Desert Mob story. In the 1980s her parents, wood-carvers Walter Pukutiwara and Topsy Tjulyata, were key figures in establishing Maruku Arts, specialising in punu (wood carving), based at Uluru. Kulitja attributes her involvement in the arts to them, her daughter and granddaughter in turn. Cultural transmission in vivid demonstration. The rest of Kulitja’s biography is also relevant: she is active not only with Maruku but with Tjanpi Desert Weavers, she is a director of the NPY Women’s Council, a member of the Mutitjulu Aboriginal Corporation and belongs to the Central Australian Aboriginal Women’s Choir. With the choir she has travelled and performed in Germany and Washington DC; they have been the subject of a feature-length documentary. This busy life offers a glimpse into the cultural vitality of desert Aboriginal communities, despite all their challenges.

It is this vitality that is the essential ingredient of Desert Mob’s success, captured by Kulitja when she spoke of the mob as “black-skinned proud Aboriginal people” (her Pitjantjatjara translated eloquently by Linda Rive) and when she created an image of their art, travelling into Alice Springs from across the surrounding desert lands, carrying with it “a great deal of cultural power”. She had a digging stick in her hand. With the help of fellow artists Nyunmiti Burton and Niningka Lewis she sang and danced the story of a woman travelling, holding the stick above her head, dragging it along the ground, leaving a trail: a metaphor, she said, for all the desert journeys of all the artworks that are eventually hung above people’s heads on the walls of the gallery or placed on plinths.

These three women coming together on stage to sing the show open also says something about the democratic nature of Desert Mob. The cultural authority of Kulitja and Lewis is undiminished by their relatively modest artistic contribution. Both are showing with Marurku Arts, small figurative works in acrylic on plywood, interesting in their story-boarding of the Seven Sisters story but not works of great impact. Burton though, showing with Tjala Arts, based at Amata in the APY Lands, has contributed in collaboration with Jennifer Ingkatji a major work in scale and vision, Ngayuku ngura – My Country, acquired by a national institution. Around a central axis the artists have densely dotted their song of country in great swirling eddies of significance. Tracks and stopping places are recognisable in the spiralling movements, suggesting a story of travels and events along the way. Whatever its particularity, the painting certainly sings.

Paintings of the calibre of the Burton-Ingkatji collaboration create the dominant impression at Desert Mob 2018, but just as numerous are characterful, often exploratory but more unassuming works; together they make up the gamut of the exhibition’s interest. It is essentially the art centres who curate the show. Their direction and fortunes fluctuate according to the interplay of many factors – the rise and passing of cultural leaders and of practitioners of talent and vision, events in community life, the coming and going of art centre managers, demands of the market, to name some.

For a number of years art centres from the APY Lands have been in ascendancy and they show no sign of ceding their position this year, with four of the seven hanging exclusively large-scale canvasses, close to two metres wide, a metre and a half high, and all of them works about country as seen through a distinctive but varied Aboriginal iconography. Among the four, Iwantja Arts has been especially noteworthy for its diversity in subject matter and format, but this year its acclaimed figurative artists – Vincent Namatjira, Tiger Yaltangki, Kaylene Whiskey, J. Pompey – were all absent (Mr Pompey has passed away, while the others were in demand elsewhere, including the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in Melbourne to show in A Lightness of Spirit is the Measure of Happiness).

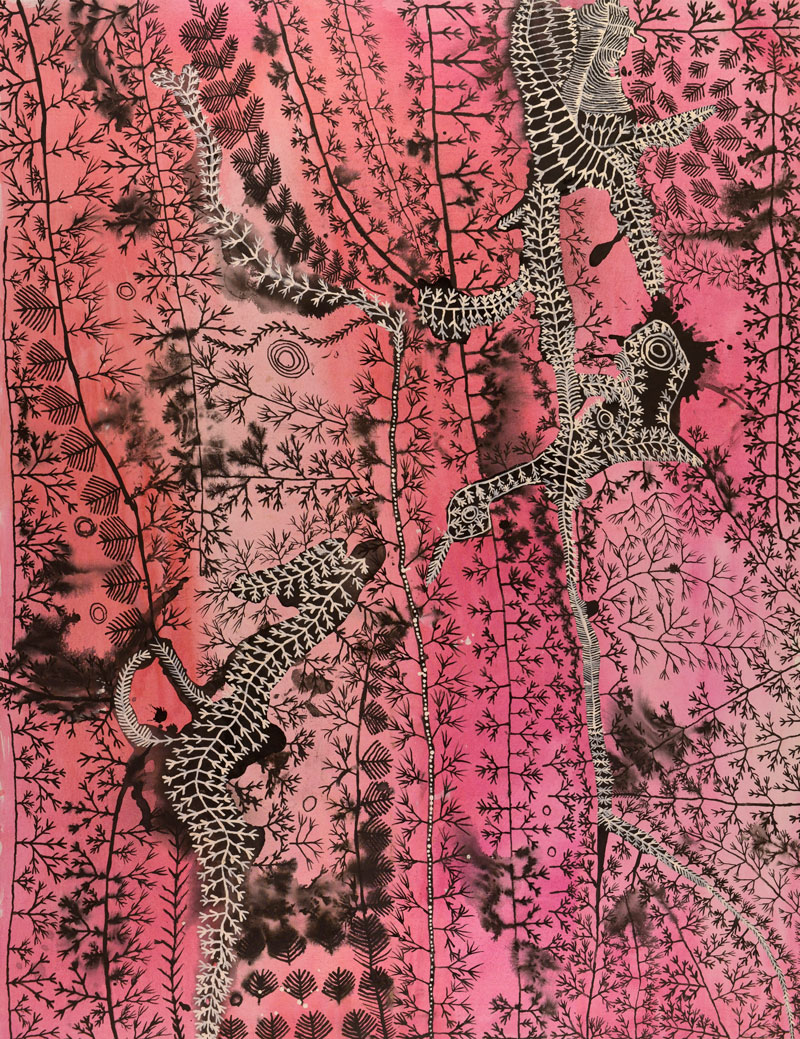

This allowed Iwantja to demonstrate its competitiveness in large work about ngura and tjukurpa, country and its songs, for the high end of the market. These are things that art centre managers must think about but it’s best when artists don’t, when the “cultural power” Kulitja spoke of remains the focus. In the ambitious hangs of the four APY centres – Iwantja, Tjala, Kaltjiti and Tjungu Palya – the works’ cultural power, inseparable from their aesthetic achievements, doesn’t miss a beat. I single out for mention Peter Mungkuri’s beautiful handling of rose-coloured washes underpinning an intricate tracery in ink of country mapped by plant life; titled Ngayuku Ngura (My Country), it is a work in similar vein to his General Painting Award-winning Ngura in this year’s NATSIAAs, though its use of pink hues sets it quite daringly apart.

Betty Muffler, just last year acknowledged by the NATSIAAs as an emerging artist, demonstrates a mature confidence in eschewing colour as she thinks and feels her way around the canvas, as she describes it, cuing a reading of the painting, Ngangkari Ngura, as a mind map, fertile and generous, complex in its inter-connections, as befits the ngangkari (healer) that she is. She speaks of the motifs as representing rockholes and the water flowing between them, at the same time as being about her ngangkari work, the black and white painting a persuasive demonstration of the inseparableness of country and its people. Mungkuri and Muffler are both showing with Iwantja Arts.

I could equally speak about daring and skill united with a singularity of vision with regard to Yaritji Young’s Tjala tjukurpa – Honey ant story, monumental and electric, in colour, complexity and movement; Wawiriya Burton’s soft yet sweeping lyricism, in pale pinks and greens, in her Ngayuku ngura – My Country. Both women are showing with Tjala Arts. The list could go on, through the APY art centres, across the coherent showing by Papunya Tjupi artists, with seven paintings about their country, united by the judicious use of metallic paint in a warm bronze hue, and on to standout works by artists from a range of other art centres, including ceramics, works on paper, and photography, specifically Feral Invasion by the always interesting Robert Punnagka Fielding (Mimili Maku Arts). My concern though is to place as much emphasis on the other kind of offerings from Desert Mob, that together open its wide window onto desert Aboriginal life.

Historical subjects are not always dark. Mission days at Hermannsburg/Ntaria, for instance, are often evoked with affection in the narrative painting on Hermannsburg pots. Pastor Albrecht by Judith Pungkarta Inkamala is an example from this year’s selection. An early days Camel Train is vividly and fondly rendered in the small sculpted figures, “bush toys” style, by Johnny Young (Tapatjatjaka Art and Craft). However, “killing times” also make an appearance in a large-scale installation by Nancy Nanana Jackson and Judith Yinyika Chambers of Tjanpi Desert Weavers. Titled Tutjurangara Massacre (Circus Water Rockhole Massacre), it shows a shooting in progress: a European man alongside a camel, his gun raised, four dead or dying Aboriginal people on the ground, a weeping child, and two figures, a man and a woman, fleeing from the scene. The two-dimensional figures, woven from minarri tjanpi (wild harvested grass), are doll-like and the scene could almost seem playful until you are pulled up by the plug-hole wounds of the prone figures, with their trails of red-wool blood. The exhibition catalogue usefully devotes two pages to an account of this event in very remote country (near Warakurna in WA), of which there is no written documentation but an oral history that has persisted across the Ngaanyatjarra Lands since the 1930s.

Contemporary life on communities and in relation to technology and cars in particular, has often been a sub-theme in the exhibition. One car to make its appearance this year is a police paddy wagon in a work by Sally M Nangala Mulda (Tangentyere Artists). The artist chronicles town camp life with an honesty that cuts both ways, whether making observations about domestic violence and alcohol dependence or about oppressive policing. Her work this year, Two Stories, leans towards the latter: on the left side it shows an idyllic daytime scene of a family group in a creekbed, cooking kangaroo tail, in contrast to, on the right side, a night-time visit by police, their paddy wagon left engine running, headlights blazing as they approach a house in a “town camp anywhere”, as Mulda spells out in text painted onto the linen.

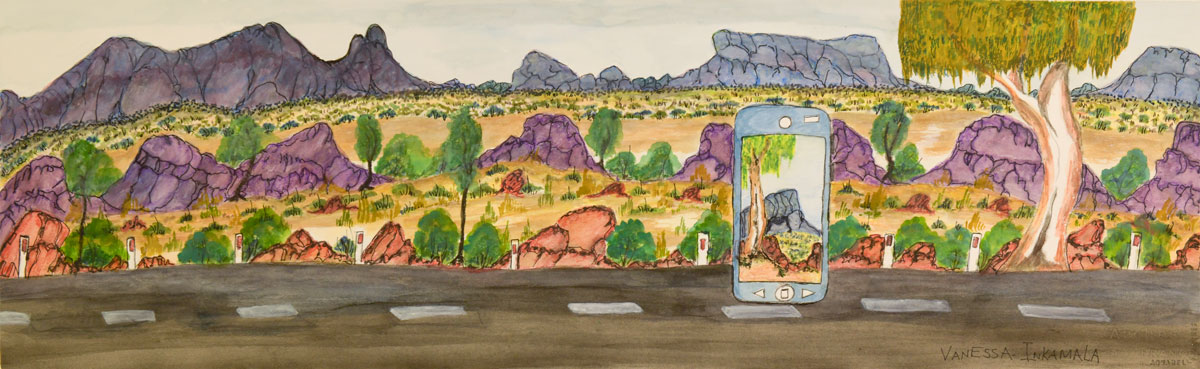

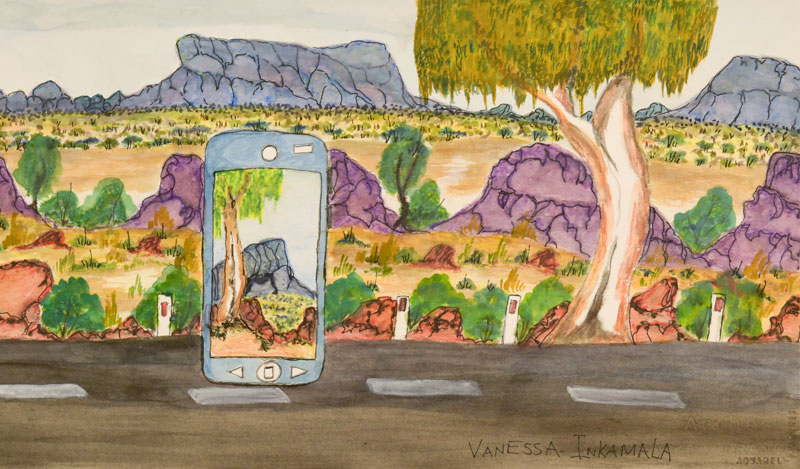

Artists of the Barkly interestingly recycle discarded satellite dishes as the ground for their depictions of scenes from contemporary life as well the eternal landscape. Vanessa Inkamala (Iltja Ntjarra Many Hands Art Centre) meanwhile paints into her “Namatjira school” watercolour landscape, Phone on the Road to Ntaria, her very contemporary process for choosing her subject: the bitumised road is in the foreground, complete with line-marking and reflector posts along the edges, and standing up on it is an outsize smartphone, in reference to how she photographs the country beyond on the trip out to Ntaria and later uses the photographs to make her paintings.

This gives some idea of the scope of approaches and insights on show in the exhibition. More arise in the symposium. Its program is often the forum for showing work arising from collaboration with outside artists and multi-media workers. In a stimulating presentation we heard this year from British artist Patrick Waterhouse and one of his Warlpiri collaborators, artist and community leader Otto Simms. In this work, over five years, Warlukurlangu Artists from Yuendumu and Nyirripi have taken documents of the colonial past – early maps, lithographs, photographs and teaching materials – through a process of revision.

More recently, they have extended the process to photographs taken by Waterhouse in the typological vein of the early ethnographers, over-painting them, some with traditional designs showing, as Simms put it, “who I am, where I come from, what my identity is in my own country, the jukurrpa that is within me”; others in black, an act of obliteration, rejecting the kind of objectifying information such images historically sought to convey. Some of this work, under the title Restricted Images, is currently on show in the small gallery space at Desart, the peak body for desert Aboriginal arts centres, which partners with the Araluen Arts Centre to present Desert Mob.

Finally I want to mention work in video, presented only at the symposium. It would be an excellent extension to the exhibition for multimedia work to be shown for the full six weeks. In the past Desert Mobs there have been some fine short interpretive films that added greatly to understanding the practice and concerns of particular artists, as well as short films, particularly animations, art works in their own right. This year we were given a glimpse into the very active cultural transmission program of Martumili Artists and Spinifex Hill Artists, titled Pujiman (meaning bush or desert born and dwelling), involving their young people in, for example, animating sand-painting stories.

The offerings also included stand-alone storytelling: the delightful Papa Tales, produced by Tjanpi Desert Weavers, featuring animated tjanpi figures in stories about the special place of dogs in desert communities; and the wonderfully entertaining Never Stop Riding, produced by Iwantja Arts and starring several of its best-known male artists as well as other men from the community. It’s a celebration of the stockmen’s heritage and fine horsemanship of their elders and forebears, as well as an exuberant pastiche of the Western, with its story of stolen gold and shoot-ups and classic one-liners.

For contemporary Aboriginal people cultural identity is not exclusively rooted in their country and dreamings. A strength of Desert Mob, from year to year, is the rich picture it gives of these core values in balance with a range of other influences and adaptations, a moving and powerful antidote to the very limited, often dispiriting impression prevailing in the mainstream media of life in desert Aboriginal communities.