“I have come here tonight for the purpose of art,” announced a very relaxed Mawurndjul at the opening of his survey exhibition – or so translated his long-time collaborator, Murray Garde. Surrounded by some 160 of his works from the previous 40 years hanging in an institution he knew well and celebrated by a crowd of art-loving admirers, this most travelled and feted of senior Australian artists – now well into his sixties – was in his element. So, you might wonder, why would such an experienced cosmopolitan need a translator?

If anyone needs a translator, it’s a cosmopolitan. At least this exhibition thought so, for bilingualism pervades its being – it’s in the catalogue and on wall texts. Was this a political point about the authenticity, sovereignty and difference of Mawurndjul and his art – as if language is such a limit to identity that Mawurndjul would always be trapped in his Kuninjkuness – or the opposite: that translation is always possible (and speaking English is not a prerequisite of being Australian)? Mawurndjul’s art takes a definite position on this question. Founded in a cross-cultural nexus, translation is the necessary gambit of his art. His delight at “the instantaneous translation”[1] of his Kuninjku words into English in a conference in Dusseldorf in 1993 no doubt reflected the magic of translation. But perhaps he also smiled because it confirmed that his gambit had traction.

“I’m only small but my head is full of ideas” is a familiar refrain in the Mawurndjul literature but less well-known is what he wanted to do about it: “I want to give you Balanda [white] people what’s inside my head.”[2] His gambit was that his fluency in painting was the magic key to doing this. Hetti Perkins, who admired his “translation of a culturally specific artistic [i.e. Kuninjku] vernacular into a contemporary international idiom,” clearly thought so.[3] But is this the end of Mawurndjul’s thinking on the matter, or did painting, as an arena of translation, hold deeper enquiry, such as epistemological questions about the limits that painting, as a language, puts on knowledge and communication? For whatever ideas filled Mawurndjul’s head, it was as a painter that he showed them to the world.

Mawurndjul has installed an army of his ancestral spirits into the heart of Sydney. A veritable battalion of mostly large bark paintings occupy the long corridor and its several annexes down to the large room at the back. They are his main troops, with some etchings and a large number of sculptural works on the side as if a standing reserve. The “intentional fallacy” (that the artist’s intentions are not reliable testimony on the meaning of his or her art) is clearly a thing of the past, as Mawurndjul played an active role in the curation and interpretation of the exhibition. He conceived it as a map of this lifeworld, which is a small patch of country about 10 km wide and 30 km long between the Tomkinson River and Mann Creek in West Arnhem Land – a network of billabongs that hold the stories of his ancestors and which he painted throughout his life.

However, the curatorial translation of this geography has been poorly realised. Even the attendants I asked were sometimes confused about which walls were which billabongs. It wasn’t simply a matter of being lost in the billabongs with little guiding narrative. The landscape layout could have worked if it wasn’t so narrowly conceived in spatial terms. Mawurndjul’s paintings have a temporal as well spatial dimension and also ecological, political and metaphysical dimensions. The walk from the beginning of the corridor to its end is a metonym of the journey from the coastal plain to the edge of the escarpment where the old rock paintings are, and it also follows his life journey from where he was raised and did his first paintings in Mumeka, to Milmilingkan, where he now lives. Maybe I am reading too much into this arrangement to say it also moves simultaneously forwards and backwards in time, but maybe not, because this is how Mawurndjul conceives each of his paintings. He doesn’t depict place as landscape but paints its historical being: how the past is always pressing forward into the now, and how he brings its ancestral histories with him into the future.

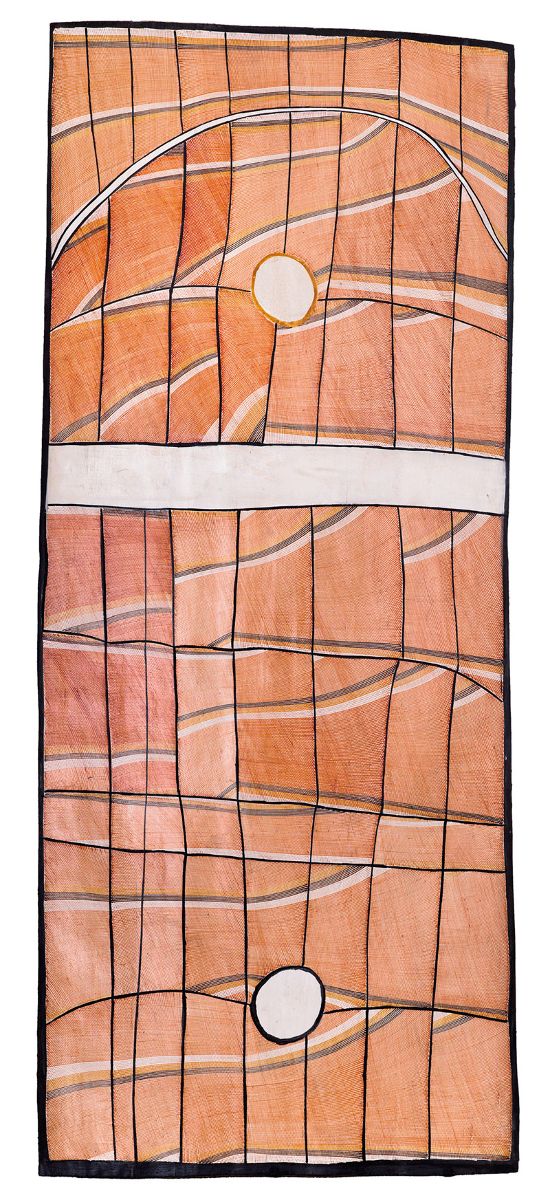

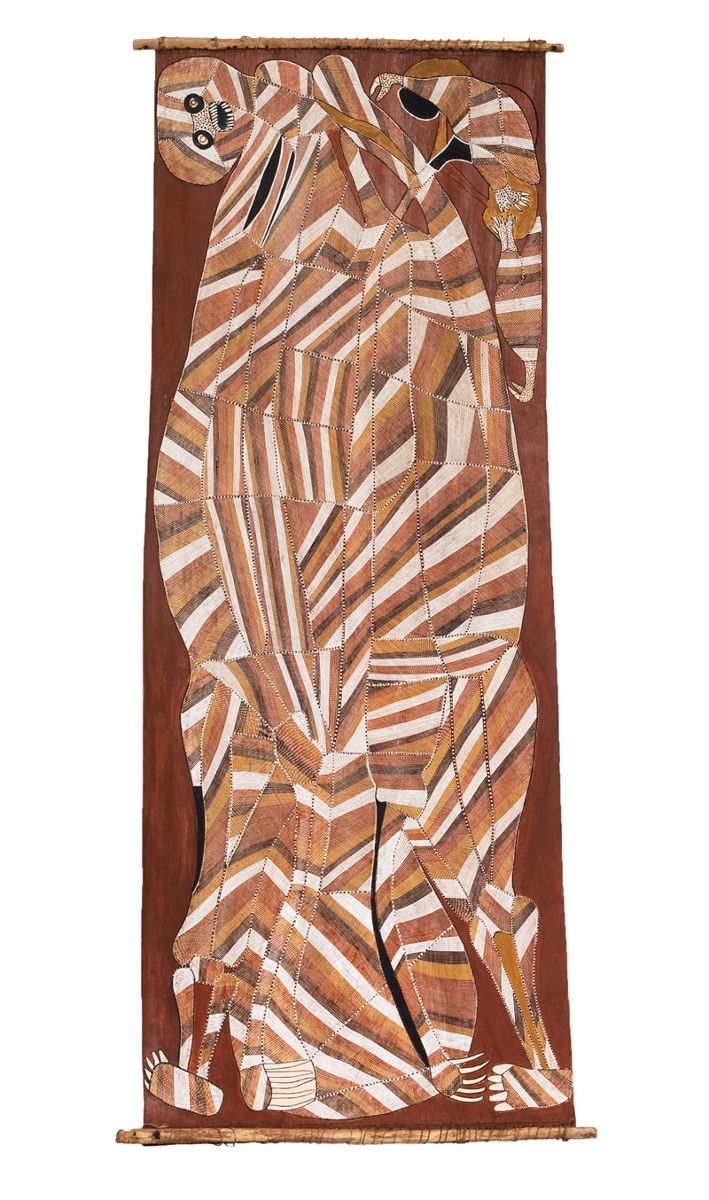

Mawurndjul’s paintings are about his country but he is a history painter, not a landscape painter. Most of his paintings are portraits of ancestral Beings that rise up to face us. This is also the case with paintings that have landscape names, such as “Billabong at Milmilgkan” and his more abstract Mardayin (ceremonial) paintings. They too rise up to meet us Being to being. This is most obvious in the portrait (vertical) rather than landscape (horizontal) format of his barks (which like nearly all bark paintings respect their vertical arboreal origin). Mawurdnjul’s paintings might evoke the typical landscape metaphor of light and shadow playing across a lagoon but they also recall the flickering patterns of ochred bodies dancing around the fire. His best paintings have the animated energy of the dancer not the placid surface of the lagoon. The lagoons, he warns, are dangerous. At Milmilgkan, the resident Ngalyod (ancestral rainbow serpent) – which “has waterlilies growing out of her body” – is particularly dangerous. “She killed lot of old people [ancestors]. I have depicted the bones of the women she ate.”[4]

Mawurndjul’s largest barks, which are about the size of a good-size door, are not doorways for us to walk (or dive) through but an opening from which emerges whatever is the terrible truth of these paintings. It faces us directly as if demanding attention. Like Heidegger’s “clearing”, into which “the silent call of the earth” is drawn into the world, Mawurndjul’s animated surfaces are engaged in an event of “unconcealment” – a term Heidegger coined to denote his conception of truth as being caught in an irresolvable conflict between what could be revealed and what should be concealed: “that opposition which exists within the essence of truth between clearing and concealment.”[5]

Mawurndjul’s paintings manifest this conflict in the tension between figurative and abstract elements, in which figurative fragments – a head, eyes, teeth, claw, waterlily – emerge briefly and disappear again in the furtive movements of truth’s (i.e. rarrk’s) inability to fully show itself. Here we glimpse the task of translation that is at the heart of Mawurndjul’s practice, which in seeking to impress Balanda with the power of Djang or ancestral Being, pushed him to work through formal issues of great invention. His bands of rarrk turn inside and outside, always on the move as if to foil any who, in lingering, mistake what they see for what cannot be seen. “They can enjoy the paintings but buried inside,” says Mawurndjul, “are secret meanings they don’t need to know.”[6]

Like an Arabian dance of veils, Mawurndjul never fully reveals the secrets of (ancestral) Beings, as if this is the condition of their power. The difference between poetic and prosaic language (be it visual or other) is that the former provides suitable camouflage for Being to be present in all its power. No wonder Mawurndjul was impatient with questions of iconography and representation, as if his art could be decoded.[7] “We don’t paint the actual body [of the ancestral Being], but its power,” he said.[8] Mawurndjul did not need to know the story or the iconography or recognise what was being represented in Balanda art to appreciate its power. Diane Moon recalled his “fascination with the universal reverence for the numinous” in icon paintings he saw at Rijksmuseum.[9]

Other geographies and histories also bear on Mawurndjul’s work. His skills in ceremonial body painting were recognised early on, which is probably why he also began painting barks at an early age – in the mid-1970s – which by then had become a useful trading item in an emerging cash economy. These relatively small barks were destined for the tourist and primitive art markets, mysterious destinations beyond the horizon of everyday life in Mawurndjul’s homeland. For those who had a yen for painting it did provide a platform for pushing their talents in new directions, but it was an impoverished aesthetic practice compared to the full embodied experience of ceremonial performances and the prestige that came with it. In Kuninjku ceremony, it is the dancer, not the painter, who is king.

.jpg)

Mawurndjul’s sense of what a painter could be changed when, in 1983, he visited Canberra. He knew a sacred site when he saw one, and the newly opened National Gallery quickly showed him there was more to Balanda art than the tourist and primitive art trade. Here painting was king. He was also affected by the “deeply empathic recognition and respect from the Canberra arts community.” His long-time friend Jon Altman credits this visit as the catalyst for Mawurndjul’s decision to purposefully “engage with western arts audiences and markets,”[10] something that required a whole new mindset and a new type of painting.

Judging by the direction in which he took his painting, Mawurndjul saw his future in the scale and aesthetic bravura of Balanda fine art. From this point he was on a quest for new forms of visual expression that could match Balanda art and, in the process, translate his Kuninjku inheritance into this Balanda idiom. There was a political dimension to this and also an historiographic one Particularly striking for the art historian is Mawurndjul’s art historical consciousness: “My bark painting is based on all of the old people who were artists but have now died.”[11] More than a nod to his artistic genealogy, Mawurndjul has a keen sense of this genealogy as an art history, and of his destiny to make it part of the wider history of art he encountered on his travels. This made him acutely aware of the new world he inhabited and the innovations it required: “I changed the law myself. We are new people. We new people have changed things.”[12] Because the exhibition provided little sense of the traditions out of and into which he painted, this major historical and aesthetic achievement of Mawurndjul is kept from view.

From an art-historical perspective, Mawurndjul’s main achievement is to have steered the West Arnhem Land tradition into the contemporary currents of global art history. “Balang [Mawurndjul’s skin name],” said Garde, “has always been interested in all art from every era and cultural background and enjoys taking his time to examine the works of the great European artists on his trips to important galleries in Europe.”[13] It is only natural that, like most artists, Mawurndjul measures his achievement, stimulates his thinking and gains confidence in his own worth as a painter by comparing his paintings to the best he encounters. He also watched closely the impact that his painting had on Balanda, their ability to feel its power and his ability to “see” Balanda painting: translations that gave him confidence in his ambition.

It says something about the transcultural potential of art that a man of Mawurndjul’s background, a bush hunter sustained by ancestral spirits, could find so much mojo in the white art world as well as a good source of income. “If it’s a good gallery,” he said, “I’ll want to be involved. It can be good fun, too.” He had found a new and rich hunting ground. The language of painting, as an autonomous poetic discipline, was a lifeline – as if here, on these grounds, he could match Western art. Indeed, his technique became so rigorous that his real subject seems to be his conceptual approach to painting. He is quite upfront about this. Keen to emphasise that he is first of all a painter, he speaks a lot about technique, which in Kuninjku traditions is the practice of rarrk or crossed lines (crosshatching). “Sometimes it makes me cry. I worry about the crosshatching. I’m always thinking about it. And then I keep doing it.”[14]

“Rarrk”, says Mawurndjul, “is only what we see on the surface, like the skin,”[15] and few can paint lines with his finesse, arrayed as thin meshes of vibrating tones that sing across the painting’s surface as if it was breathing skin – creating the distinct optics of his signature style. This is what makes him such a great colourist. Despite the limited range of hues, he creates veils of colouration in impressionist-like fashion from the mixing that occurs in our perception (i.e. in our head) of variegated patterns and shifting tones. The breakthrough in terms of Mawurndjul’s professional career in the Balanda artworld was understanding how these patterned lines could build scale. One can see why scale would impress an artist transported from the intimate bush environs of ancestral billabongs to the monumental forms of Balanda land, its art and artworld. Perhaps seeing those large examples of American abstract expressionist canvases in Canberra simply piqued his competitive streak; for whatever reason, from 1988 scale would become his calling card.

Mawurndjul is not the first to paint large barks; rather, his achievement as a painter is to make scale an integral attribute of his style. He does this by building his skein of lines into cubist-like facets that stretch and fold, twisting in and out across the full length of the bark. In this way, his fine brushwork reverberates across and into larger elements like a musical scale that ascends and descends in various rhythms. The concentration required for such fine crosshatching is masterful but more masterful – and what makes Mawurndjul one of the great artists of the late-twentieth century – is the poetics of these scalar movements that like an orchestral arrangement ripple through the whole composition, creating an infinite well of pictorial space that he pulls into the composition. By comparison, his painting on the more restricted solid shapes of the sculptures and poles (lorrkkon) tend to the decorative. A similar point can be made about the etchings, which seem like sketches of ideas for paintings.

A familiar curatorial problem with hanging a large number of artworks that look much the same is that you can’t see the exhibition for the art. In part this reflects the difficulty of the task, but in this case it also reflects a reluctance to draw on the methodologies of art history – as if contemporary art is post-historical. Retrospectives of major white Australian artists in Australian state art galleries, such as the smaller exhibition of John Russell currently at the nearby Art Gallery of New South Wales, have an historical ambition that make the curatorial treatment of Mawurndjul’s aesthetic breakthroughs appear cursory. The platitudes are many and deserving, but Mawurndjul’s achievement deserves more than platitudes.

The real miracle of Mawurndjul’s art is how his art developed from its relatively limited purpose in the late 1970s to what we imagined bark painting could be, over the next twenty years. This makes his oeuvre ripe for traditional art-historical analysis of style and periodisation. Moreover, Mawurndjul has an acute art-historical sensibility. You could say it is his obsession. “There is,” he said, “from long ago another history that the bark paintings do not forget.” His opening words in his catalogue interview are:

I will tell you a history about long ago in the time of my ancestors and also about the new time of the new generation. Balanda (non-Aboriginal people) are something new … Balanda come here and they ask me: “So, you people don’t know about your past …” But I say, “I have two things: the history and the new generation.”[16]

The exhibition’s title – Mawurndjul’s dictum “I am the old and the new” – is a good start but what this means needs to be shown. “I like to see,” Mawurndjul said, “how the crosshatching has changed [over time].”[17] This alone would be enough for a substantial exhibition, but imagine an exhibition that showed how he took the West Arnhem Land tradition into a world art history.

The development of Mawurndjul’s rarrk is there to be seen but the paintings are not hung in any order that easily reveals it. Nor does it tell the story of his decline as an artist in the 21st century, although the decline is plain to see from about 2004 when, as often occurs, a late painting is hung between two powerful works from the 1990s. The only author in the catalogue who faces up to this decline is Altman. He blames the 2008 Northern Territory intervention, but the decline set in before then. Whatever its reasons, Mawurndjul has not yet found the means to sustain the formal invention of his earlier work. Of late, several Yolngu artists working in eastern Arnhem Land have seized the baton: Napanyapa Yunupingu, Nonggirrnga Marawili and Garawan Wanambi. Like Mawurndjul once did, they are the painters now taking Arnhem Land traditions into increasing abstraction with new energy. And once an artist seizes it by the tail, as Mawurndjul did in the 1980s and 1990s, history waits for no one.

Footnotes

- ^ Marie West, “Rarrk Master” in Natasha Bullock (ed.), John Mawurndjul: I Am the Old and the New, Sydney and Adelaide: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia and Art Gallery of South Australia, 2018, p. 331.

- ^ John Mawurndjul, “I’m a Chemist Man, Myself,” in Hetti Perkins (ed.), Crossing Country: The Alchemy of Western Arnhem Land Art, Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2004, pp. 135–39 at p. 137.

- ^ Hetti Perkins, “Mardayin Maestro” in Bullock (ed.), John Mawurndjul: I Am the Old and the New, p. 20.

- ^ John Mawurndjul, “I Never Stop Thinking About My Rarrk: John Mawurndjul in an Interview with Apolline Kohen,” in Christian Kauffmann (ed.), “Rarrk” John Mawurndjul Journey Through Time, Basel: Museum Tinguely, 2005, pp. 25–28 at p. 27.

- ^ Diane Moon, “Powerlines,” in Bullock (ed.), John Mawurndjul: I Am the Old and the New, p. 331.

- ^ John Mawurndjul, “I Never Stop Thinking About My Rarrk: John Mawurndjul

- ^ Garde, in Bullock (ed.), John Mawurndjul: I Am the Old and the New, p. 46.

- ^ Mawurndjul, Crossing Country, p. 138.

- ^ Diane Moon, “Powerlines,” in Bullock (ed.), John Mawurndjul: I Am the Old and the New, p. 331

- ^ Jon Altman, “The political ground of creativity” in Bullock (ed.), John Mawurndjul: I Am the Old and the New, p. 331.

- ^ Mawurndjul, Crossing Country, p. 139.

- ^ Ibid., p. 136

- ^ Murray Garde, “Ngadjalyolyome Balang Mawurndjul (Let me tell you some stories about Balang Mawurndjul)”, in Bullock (ed.), John Mawurndjul: I Am the Old and the New, p. 44.

- ^ Mawurndjul, Crossing Country, p. 139.

- ^ Mawurndjul, in Bullock (ed.), John Mawurndjul: I Am the Old and the New, p. 49.

- ^ Ibid., p. 49.

- ^ Mawurndjul, Crossing Country, p. 138.