The wealth of “discovery art” in Colony is infused with the artists’ enchantment in newly discovered things. But this curiosity has a darker side, and it is from this tension that Colony seeks a new spin on colonial art that addresses urgent questions of national heritage. The old spin – the grand narrative of terra nullius and its stories of White Australia, the Course of Empire and its civilising mission – lost traction long ago. The nation is, as Mark McKenna put it recently, at “a crossroads”: “The time for pitting … one people’s history against another’s, has had its day.” We can no longer cling “to triumphant narratives” that ignore “the violence inherent in the nation’s foundation.”[1] Colony makes its stand with a new grand narrative: “Frontier Wars.”

At least since The Aboriginal Memorial unequivocally put frontier wars on the table at the bicentenary Sydney Biennale in 1988, the art world has felt a moral imperative to expunge its bad conscience. Thirty years is a long time to be chased by the black dog, and reviewers sensed Colony’s impatienceto move on. In her enthusiasm, Calla Wahlquist got unduly ahead of herself – or at least her editor did: “Duelling exhibitions at the National Gallery of Victoria present art that erases Australia’s ugly history, with Indigenous art that speaks to it.”[2] If only it was so easy: articulating Australia’s black and white history is not a matter of erasing the ugly bits.

Colony assembles a wonderful cast, and while the script could be sharpened in places it is thoughtful, thought-provoking and not wanting in boldness. A few well-tried tricks are played, such as Indigenous interventions in the colonial archive, but Colony also tries an innovative dramaturgy. In his review Tyson Yunkaporta aptly described it as “the settler section downstairs and … the blackfella area upstairs.”[3] An edgy idea and a gamble for sure but one worth taking – anything to break the “Great Australian Silence” that weighs on colonial art like a heavy shroud. Further, in resonating with the Manichean relations of colonialism (evident in the essentialisms of current Australian identity politics) it builds its oppositional relations into the structural logic of the exhibition’s storytelling. Quoting NGV curator of Indigenous art Myles Russell-Cook, Yunkaporta wrote: “this disparity is deliberate,” the intention being a dialogical space for “competing versions of history, which addresses gaps and provides a way to make sense of the past.”

.jpg)

This dialogical space (of competing histories) was more apparent in the catalogue, which folds the stories more directly into each other. With two floors separating the two, the exhibition keeps them well apart. In each stairwell is a lightbox work by Jonathan Jones, but if they were meant to connect the two exhibitions their relationship to either is obscure. Yunkaporta suggests the intended effect: the curators conducting him through each exhibition, “were in constant dialogue, continually shifting between opposite perspectives that were somehow harmonious and unified.” Clearly impressed, he called it “an unimaginable sweet spot at the interface of competing histories, challenging everybody but offending no-one.” This rang alarm bells for me. The frontier wars are not this easily reconciled. Besides, curator talk is not the exhibition.

The dice were loaded, as they invariably are in the frontier wars. The resources put into the whitefella section vastly outweighed those put into the blackfella section. At a more fundamental or conceptual level, downstairs is the archive – the foundation and law – from which upstairs takes its bearings. So downstairs is the colonial unconscious. Only here can any new grand narrative take shape. The architecture reinforces this hierarchy as upstairs is like an attic, a dreaming space to which viewers ascend for redemption after their Dantesque tour downstairs. This is even evident in the thematics: upstairs the rooms bear spiritual and philosophical names such as “absence,” “presence,” “lament”; while downstairs is represented through a very matter-of-fact nomenclature, such as “Sydney 1810–50s.”

Yunkaporta had a different experience. He came away feeling “the story upstairs is inevitably entwined with the one below,” like two lovers reconciling. Imagine if they really did entwine physically, spatially, like a double helix, the DNA of a new national mythos? This would be a major achievement, although in my view upstairs is entwined with downstairs like a python squeezing its prey. Something special, unexpected and amazing is required from upstairs. Julie Gough’s Chase blocking the entrance was a nice touch, but generally the hang needed a sharper focus for it to be more than another exhibition of Indigenous contemporary art – except for the dark room near the back in which a serpent reared and hissed. This was Steaphan Paton’s searing Cloaked combat. Paired with piles of shields and other cultural objects strewn in a line on the floor like bodies slain in battle, their ghostly spirits rising in the large flanking portraits by Leah King-Smith and Brook Andrew, it was inspired curating. Imagine it as the antechamber to downstairs.

The use of shields and other cultural objects have become a signature of contemporary Australian exhibitions because their iconic presence has a talismanic surrealist edge that cuts into the national unconscious, puncturing the Great Australian Silence. It works but is overused. Downstairs thirty-four shields from southeast Australia stand to attention in a straight line, guards of honour welcoming us in. Like the ubiquitous Welcome to Country, they call up a local ancestral presence but at the same time can too easily settle the nation’s bad conscience. These now commonplace gestures are not enough to upstage the grand narrative of Empire that is built into the logic of colonial art. Without a new paradigm underpinned by its own semiotic logic (or language), these well-meaning interventions can seem like trophies of Empire – such as those displays of spears that featured in nineteenth-century museums and places like Melbourne’s Savage Club. To feel the presence of frontier wars in colonial art we need the rattling of spears or Paton’s thud of arrows hitting their mark.

Losing its shine won’t displace a paradigm. Only a better story can do this – and a story is only as good as its telling. Colony begins its story well. Histories of Australian art generally begin diffidently, as if they are not sure where the beginning begins. At what point does the art of Empire art become Australian? Colony does not hesitate: the early discovery art in the first rooms throws open the curtain on the first frontier. To finish the story, an equally gripping ending is needed and in-between enough action that is geared to the semiotics of frontier wars. Wisely Colony doesn’t purport to tell the whole story. Its focus is early colonial art: discovery art and its transition into the art of settler colonialism. Art historians usually end this period in 1850, before the discovery of gold and self-government put the colony on a new course. The problem for the NGV in ending the story then is that Melbourne, which only began as a rogue outpost of Tasmanian pastoralists in 1835, will have little presence. Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth are in similar boats. As it is, Sydney dominates and even little Hobart has a greater roar than Melbourne.

Pride comes before a fall. Using the founding of the NGV in 1861 as an excuse to tack on another decade is a bullet to the foot, as it plays straight into the discredited grand narrative of Europe’s civilising mission. The last work downstairs, a large watercolour of the commanding colonial building in which a museum of art was officially opened in 1861, brings the exhibition to an end with a whimper rather than a bang. This imposing library, gallery and museum was a triumphant apotheosis of Empire, but no one blinked at the front. The continent may have swallowed Burke and Wills in 1861 but the next year John McDouall Stuart successfully conquered it. Within a decade the Overland Telegraph Line had been built and the frontier wars were ignited with new fury.

While the discovery art of the Sydney region is well represented, that of the interior where the frontier wars mainly occurred has a much smaller presence. Queensland, where from the 1840s the frontier wars were bloodiest, is largely absent from the exhibition – unfortunately for the NGV no one paused to document the carnage. Frontier images mainly come to us from expeditions of explorations. There is a small silhouette of Major Thomas Mitchell and one of his Wiradjuri guides, John Piper, but not the eloquent drawings Mitchell made beyond the frontier of NSW in the 1830s and 1940s. Colony is not entirely silent on inland explorations, as it touches on the post-1850s expeditions in South Australia. Representing the far north of South Australia are four paintings by Thomas Baines, including an oil in which he depicts himself dramatically shooting a giant crocodile at the mouth of the Victoria River. Why it hangs in the final Melbourne room I am not sure, and strangely given Colony’s concerns, his paintings of confrontations with indigenes are omitted.

But the occasional skirmishes depicted in such discovery art were not the battlelines of the frontier wars, and do not compensate for the lack of massacre stories in settler colonial art. When the frontier is depicted in colonial art it invariably appears as a happy playground for naturalists and indigenes. Once the settler colonies were established the frontier recedes from view, and in the late colonial period Australian art morphs into endless golden summers. Mostly fine art is a transcendent not imminent practice that doesn’t yield up its truths in obvious or easy ways – all of which adds to the difficulty of the NGV’s task.

This difficulty is why some of the upstairs artists donned infra-red glasses to reveal the contours of other stories hidden beneath – as in Gordon Bennett’s two early paintings that pioneered this approach. In reprising the epistemic violence of colonial images, Bennett’s paintings amplify rather than muffle the symbolic relations of its texts. He called them “psychodramas.” Brook Andrew, Leah King-Smith and Christian Thompson develop this approach in different ways, as if each is a curator re-assembling the archive to tell old stories anew.

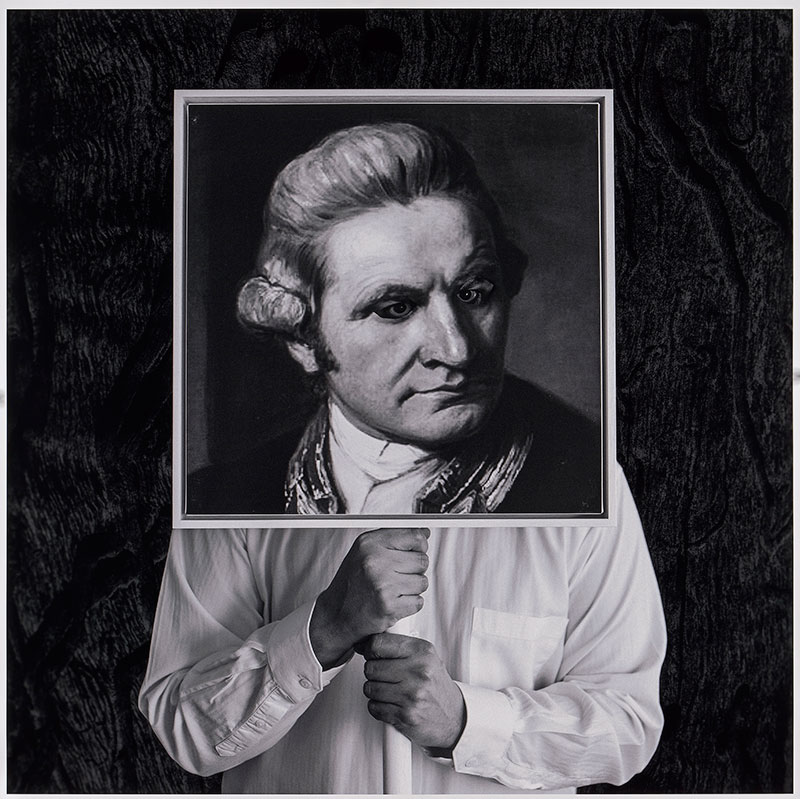

Downstairs is caught between telling the familiar whitefella story with barely a confession in sight and using some wall texts and “other” stories – mainly seen in vitrines – to prod at the nation’s bad conscience. For example, once past the row of shields, a wall text reminds us that Cook didn’t “discover” Australia, but the art in these first rooms tells a different a story. Here are too many Cooks. If helicoptered in from upstairs, Christian Thompson’s Othering the Explorer: James Cook would have prompted more nuanced thoughts on the idea of discovery. Imagine it as a warning sign at the end of the long corridor that, like Alice’s rabbit hole, takes us into this rich archive of discovery art. As it is, once you’re dropped into this Pandora’s box you soon get lost in so many ecstasies of discovery. This has its own joys, performing as it were the meaning of this art.

A highlight of the exhibition, these first rooms are a cornucopia of mainly natural history (rather than fine art) images that tell with rarely seen detail and clarity a story of the first flush of European exploration and the first twenty-five years of the penal colony at Sydney. It overwhelms at first, but there is an order at play. Following a chronological sequence, the works have been grouped by a typology of subjects. On one wall are topographies of the fledgling colony, on the opposite ethnographies of the local indigenes, and further in a room of botanical and zoological studies. This familiar discourse of European possession demonstrates the old maxim that knowledge is power, but because it is ordered mainly by type or similarity rather than in a relation of differences, its psychodramas aren’t reprised.

Geared to curiosity, discovery art belongs to science not conquest. But as Lisa Slade argued in her exhibition of 2010, Curious Colony (in which the difference of blackfella and whitefella was in close consort), in this colonial context curiosity is “double-edged.” The double-edge (or hinge of difference) is science and Empire, and it is very apparent in Colony, especially in the first room. There could have been more attention to how this difference structures a discourse (or tells a story) as, for example, occurs in the telling differences between the original watercolours made on the frontier for science and their translation by engravers and oil painters in Europe into images of Empire – a semiotics that Bernard Smith analysed so long ago.[4] Examples of both are on display, but they are arranged too haphazardly to reveal the semiotics at work.

From the wonderland of the first rooms we plunge into the gloomy environs of Sydney’s very own penal colony, Newcastle. The room’s generously spaced hang with a small number of works made over just a few years brings the genre of discovery art into sharper focus. The change of pace is well judged. In the dark gothic imaginings of its convict artists, particularly Joseph Lycett, overseen by the ambitions of amateur artist and commandant Captain Wallis and the local Indigenous headman Burigon who enabled this project, the turbulent undercurrents of frontier relations are brought home. Oddly absent is Lycett’s album of the Indigenous frontier, in which is depicted his own spearing – while several examples of his humdrum picturesque illustrations of settler colonial landscapes are included elsewhere.

From Newcastle we step into a well-settled and self-satisfied Sydney. A new phase of colonialism comes to the fore as the frontier penal colony morphs into a settler colony, and fine art conventions replace those of natural history illustrations as if to reassure the colony and the Empire of their civilising mission. In march picturesque landscapes and endless dull portraits of the good settler colonists. As the numbers of portraits increase the frontier recedes from view.

As this turning from discovery art to the fine art of settler colonialism begins to shape an emerging myth of Australian identity, the story loses momentum. In part this is because the nascent settler colony is unsure of its story. Further, because much of the art is of insufficient quality to command the gallery wall, curators of settler colonial art habitually seek to fill out their story with museum-type arrangements of crowded, mixed displays and vitrines full of various paraphernalia. This is largely the case in the Sydney room. The furniture is fascinating but not made necessary to the story. The main pushback against the colonial project occurs in the vitrines, in which many of the objects are made by indigenes, women, convicts and unknowns. They have “other” stories to tell, but they aren’t woven together into a convincing fabric. No language is extracted from this varied archive to reveal the undercurrents of this nascent colony.

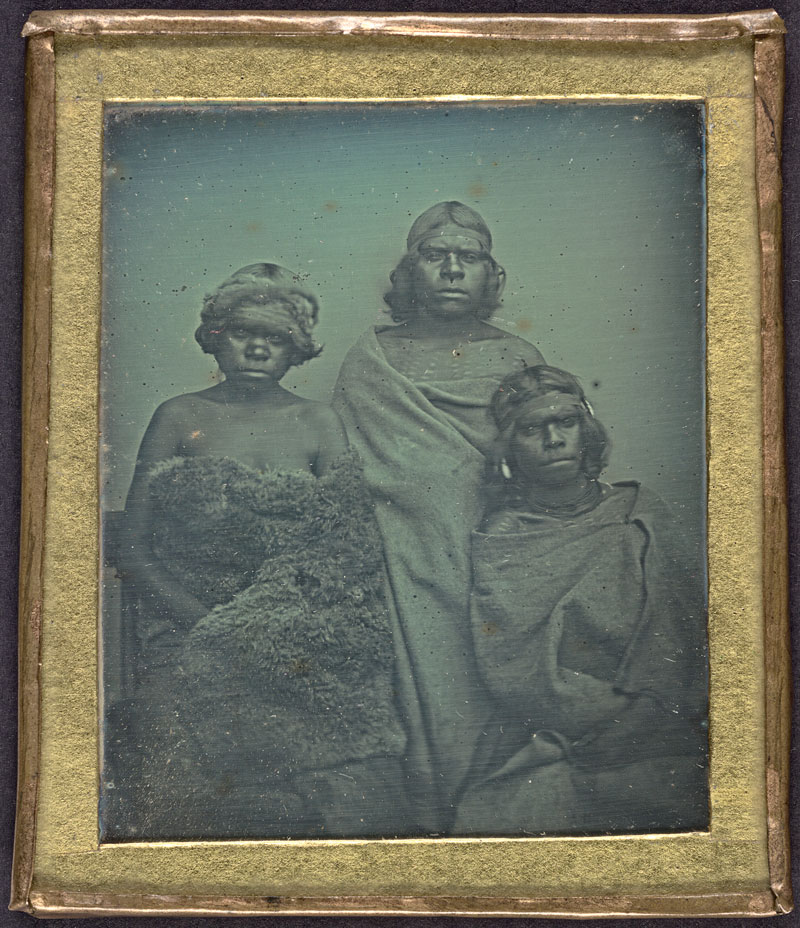

Contemporary artists (e.g. Brook Andrew) and curators (e.g. Okwui Enwezor) have made the vitrine into an imaginative format for contextualising art and exhibition discourses of postcolonial resistance. While cramped in its upstairs setting, Andrew’s vitrine installation Vox: Beyond Tasmania (2013) is a lesson in how the paraphernalia of colonialism can be made into a telling riposte to the discourse of Empire – here the relations between the Tasmanian frontier wars and scientific practices.

.jpg)

From the Sydney room we move via an intermezzo of decorative and topographical art from regional areas to the Tasmanian room, which repeats the story of Sydney on a smaller scale but with better art. You can feel the curators’ sense of relief in their hang of John Glover’s five splendid landscape paintings. Finally, a wall that truly sings. But is it a frontier song?

Glover immigrated to Tasmania in 1831 at the age of 64 to help his sons establish a farm. During the previous forty years he had made a successful career as a leading English artist in a movement that developed a reputation for mobilising landscape tropes (e.g. of the picturesque and sublime) into a language for composing allegories of national art. Glover applied a similar allegorical approach using “images in opposition” – as Tim Bonyhady dubbed this colonial semiotics – that depicted his property from both sides of the frontier.[5] But this storytelling device is not revealed in the hang. As well as a lost opportunity, it entrenched existing myths. For example, referring to The River Nile, Van Diemen’s Land, from Mr Glover’s Farm, one review began: “John Glover can’t paint eucalypts. Their branches twist elegantly into the sky, bearing none of the scars, broken branches and sharp angles that mark the trees in real life.”[6] Yet the second painting to its left features a more sharp-angled gum tree, under which lounge Glover’s English cows. The reviewer can’t be blamed for missing Glover’s arboreal semiotics, as the works aren’t paired to reveals this. Nor do the wall texts help.

Unable to look at the Aborigines enjoying swimming and hunting beneath the serpentine branches that “twist elegantly into the sky” because the memory of the infamous genocide was too disturbing, the reviewer admonished the old man: “Glover imagined the scene.” Imagine, an artist who dares to imagine? In Glover’s case, it wasn’t how the reviewer imagined, although she merely took her point from the wall text. The painting recalls a scene from a few years earlier when Glover enjoyed the company of a group of indigenes camped at the bottom of his property on the River Nile. He even invited them up to his studio to contemplate his allegories. A beneficiary and critic of Tasmania’s genocide that shamed an Empire, his paintings reverberate with stories of frontier wars if we have the ears to listen.

Colony peters out after Tasmania. In the final few rooms of Victoria and South Australia nothing new is added to the story. There is a very interesting artwork in this section, Billibellary’s mysterious ink drawing, The Lord’s Prayer, which among other things depicts an indigenous hunter with a rifle and I am guessing a horse. A few librarians have known about it, but it is something of a discovery for the rest of us. It feels like a key to unlock something new about the early colonial period, although where this work sits in the semiotics of colonial art is yet to be discovered.

In its challenges to the traditional whitefella story, Colony sets a new benchmark in the exhibition of colonial art. But without a language to articulate the frontier wars a new story cannot be written. Exhibitions think by finding in the juxtaposition of artworks a structure of difference – a semiotics – with which stories are told. The new story that Colony seeks to tell is difficult to hear when the blackfella story has been so obscured, but unless colonial art is squeezed harder to more fully exorcise its repressions it will become irrelevant to any new mythos of nationhood that is in the making. Ironically, the Indigenous art upstairs is most successful at giving colonial art a new relevance. They know white Australia has a black history, and only from this can a new post-national identity be articulated.

Footnotes

- ^ Mark McKenna, “Moments of Truth History and Australia’s Future,” Quartery Essay, no. 69, 2018, p. 73.

- ^ Calla Wahlquist, “History is messy: twin art shows that could aid Australia’s reconciliation,” Guardian Australia, 15 March 2018.

- ^ Tyson Yunkaporta, “NGV’s two-part (15).jpg Colony exhibition is a magical and unflinching look at Australia’s past,” Time Out, 28 March 2018: https://media.timeout.com. All future quotes from Yunkaporta are from this reference.

- ^ Bernard Smith, European Vision and the South Pacific 1768–1850: A Study in the History of Ideas, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960.

- ^ Tim Bonyhady, Images in Opposition: Australian Landscape Painting 1801–1890, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- ^ Wahlquist, op cit.