Directed by Fatih Akin, the 2017 film In the Fade was riveting in its depiction of the tension between Berlin’s Turkish–German community and the nationalist conservatives, who achieved success in the recent German election. It is the sort of topical conflict conjured in the title of the 2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, Divided Worlds. But curator Erica Green, director of the Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum, had a different, rather unexpected approach in mind. Observing that we live in troubled times, she posits difference – “race, religion, ideology, opportunity and power” – not as a portent of societal catastrophe, but rather as a celebration of the redemptive role of art and culture: “[These divided worlds in fact] offer us a rewarding account with something visionary and an opportunity to experience “difference” as a positive strength, an expression of natural order.”

It’s a proposition perfectly encapsulated by Angelica Mesiti’s, two-screen video installation Mother Tongue (2017), presented at the Samstag Museum – one of the five Adelaide Biennial venues featuring in total thirty artists. Bringing her particular insight to the Danish context of a contemporary demographic revolution – considered largely responsible for the growth of the new nationalism and emergence of right wing parties in Europe as elsewhere – Mesiti highlights the cultural divide through architectural context. Accordingly, Mother Tongue shifts between Gellerupparken, a multi-storey, International Style, concrete housing complex – occupied by newly-arrived immigrants and regarded by Danish authorities as a ghetto – and more rarefied surrounds, including the acclaimed Jacobsen/Moller designed Aarhus City Hall (1941) and the cutting-edge, twenty-first century library and cultural centre DOKK1.

In contrast with Akin’s confronting film, Mother Tongue is a subtle, moving and ultimately optimistic work, in which the point of cultural connection is music, song and performance – variously ancient, traditional or contemporary; a group of council workers sings about the beauty of the Danish landscape; a lone Palestinian woman strums the frame drum – an instrument rarely played by women; young Gellerup men dance the celebratory Dabke and renowned Somalian singer Maryam Mursal sings Lei Lei (“I am Blue”) – a lament for places and community, which resonates with the content of the traditional Danish songs.

The Biennial’s “journey into difference” begins with the juxtaposition of Lindy Lee’s luminous beacon Life of Stars (2015) and Roy Ananda’s dark, subterranean construction as points of entry to Divided Worlds. llluminated at night, Lee’s towering, intensively perforated sculpture – positioned at the Art Gallery of South Australia’s North Terrace entrance, both traps and disperses light (and Nike Savvas’ shimmering, mirrored curtain performs a similarly light-filled entrée to AGSA’s alternate entrance).

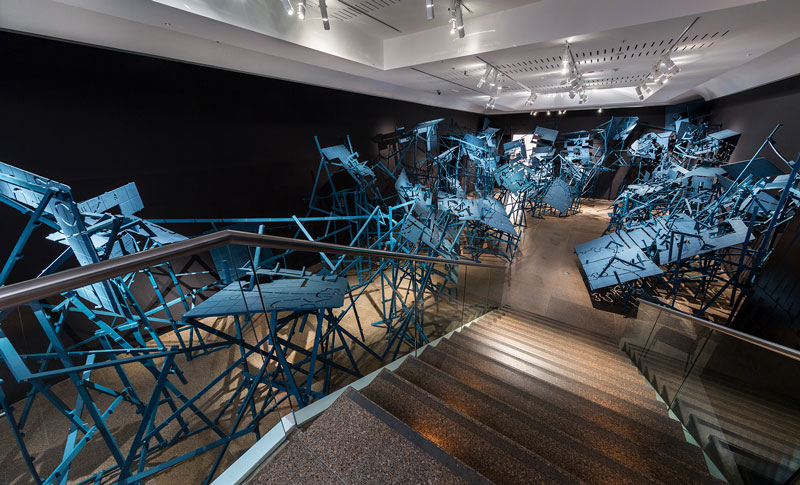

Descending to the near-stygian gloom of the basement as underworld, viewers encounter Roy Ananda’s massive, immersive installation, the most recent realisation of his exhaustive investigation into speculative fictional worlds and fandom. One of Divided World’s standout works, Thin Walls Between Dimensions is a skeletal transposition of an underground maze described in the game Dungeons & Dragons. In terms of spatial design, this grounded use of the atrium space, in which viewers are constrained to move through Ananda’s monument to fandom, is a most effective ploy.

For Divided Worlds, the equally obsessive practice of Patrick Pound has generated the expansive installation The Point of Everything. Adopting a now well-honed strategy of incorporating items from his own archive, alongside objects from the host collections, Pound has assembled a characteristically layered agglomeration of material, which includes photographs, literature, objects, paintings, vinyl records, ephemera etc., all of which literally “hold an idea of the point and pointing.”

Several editions of Aldous Huxley’s Point Counter Point (1928) proffer the kind of thematically apposite content and title that is achieved formally in Gerrit Rietveld’s sculptural Zig Zag chair (c. 1932). Groundbreaking in its strict angularity and geometry and lack of concession to comfort, it signifies an art-historical rupture, which architect/designer Rietveld, who was a member of the avant-garde De Stijl movement, philosophically committed to utopian ideals of equilibrium, simplicity etc., realised through the purity of reductivist, geometric abstraction.

Given the thoroughness of Pound’s methodology, it seems somewhat churlish to draw attention to an example of a pointing figure with especial relevance to the city of Adelaide. But Pound appears to have overlooked Adelaide’s remarkable surveyor-general Colonel William Light, whose statue with outstretched right arm pointing towards the city of Adelaide (and AGSA itself) oversees his cityscape from the elevated location of nearby Montefiore Hill.

The elegant, nineteenth-century Museum of Economic Botany in Adelaide’s Botanic Garden furnishes a synchronous backdrop to Tamara Dean’s In Our Nature (2017); a commissioned participatory project – resulting in a suite of photographic images depicting young women interactingwith and provocatively immersed in the landscape – photographed over successive seasons in the Mt Lofty and Adelaide Botanic Gardens. Flanked by two magnificent magnolia grandiflora trees, the 1881 museum houses permanent, specific collections of plants, for which the prototype was established at London’s Kew Gardens in 1847.

The watery aspect of many of these works, as well as the Ruskinian-like veneration of nature (and the heedlessness) inevitably recalls the Pre-Raphaelites (in particular J.W. Waterhouse and J.E. Millais), but is there also a stirring of the Australian gothic? (What is lurking beneath the water?) In the nearby Palm House – a splendid Victorian glasshouse imported from Germany in 1875 – Christian Thompson’s soundscape as lullaby provides a haunting backdrop to a precious collection of the distinctive flora of Madagascar.

(1).jpg)

By contrast, transgressions against nature are inherent within the overtly opulent, baroque sculptures of Timothy Horn – one of a number of Samstag scholars in this biennial. The extraordinary, super-sized jewellery pieces of Tree of Heaven 8 (Trident) allude to the fate of the infamous Trident tree – used by the Nazis to hang members of the Resistance – subjected, like the surrounding forest, to ongoing radiation exposure as a consequence of the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl.

Utopia or dystopia? While the ephemerality of Pip & Pop’s fantastical, sugary grotto may hint at the fleeting, yet seductive nature of material pleasures, Green states in her curatorial essay that in their celebration of abundance, these fluorescent topographies of sugar suggest consumerism. In this connection, it is worth pointing out the artworld associations with the material itself (now incidentally a pariah amongst foodstuffs). Interestingly, it was Henry Tate of the British sugar refining company, Tate & Lyle, who used his vast fortune to found Britain’s Tate Gallery in 1897 (and also donate to the gallery his collection of pre-Raphaelite paintings that feed into Tamara Dean’s biennial work).

Featuring newly commissioned and expanded works, in tandem with existing works, Divided Worlds riffs on binaries, demarcations, parallel universes, alternately overt or implied (and in which lighting design frequently plays an integral role). Consider Maria Fernando Cardoso’s ebullient, erotic flora, which provide a brilliantly hued and wayward counterpoint to the dramatic austerity of Kirsten Coelho’s elevated and pared-back, white porcelain vessels – shrouded in darkness, theatrically lit. From the arid Anangu Pitjantjara (APY) lands, the Ken Sisters’ vibrant, collaborative paintings of their tjukurpa reveal contrasting approaches to John R. Walker’s abstracted landscapes of the Flinders Ranges (an ancient terrain also painted by Hans Heysen in an additional point of difference).

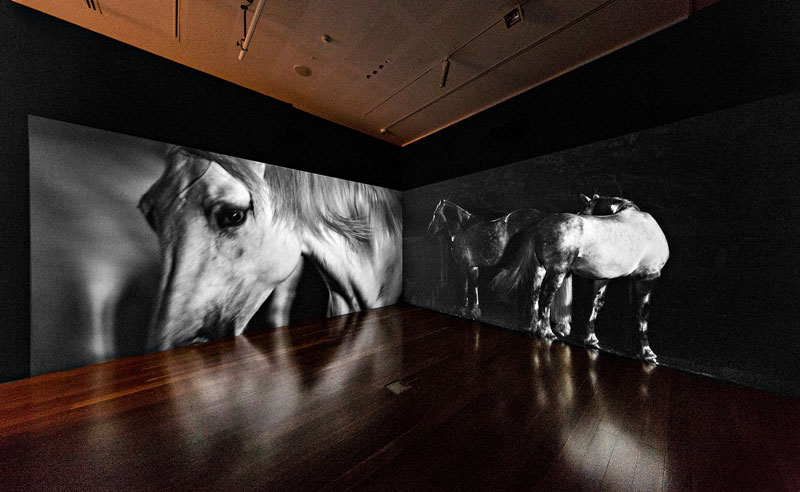

On the upper level of the Samstag Museum, overlooking Emily Floyd’s Icelandic Puffins (2017) and in the vicinity of the (differently nuanced) socio-political works of Khaled Sabsabi and Vernon Ah Kee, Amos Gebhardt’s video meditation Lovers (2018) depicts a mesmerising courtship ritual between two horses. For gallery visitors who seek trans-institutional dialogue, the provocative tossing of manes and horses’ tails brings to mind Patricia Piccinini’s hair “paintings” at AGSA. Attentive viewers will also identify the Botanic Garden’s Palm House reflected in the eyes of Christian Thompson’s colourful, flower-strewn self-portraits at the Samstag Museum.

Reinforcing Green’s art-as-panacea proposition, in his speech at the media launch, Festival co-director Neil Armfield alluded to the “longing for healing and becoming whole.” Like Khai Liew, whose family fled Kuala Lumpur in 1968, Sabsabi’s family were part of an exodus that escaped Lebanon’s bloody civil war (1975–90). Sabsabi has described his affecting 99 Names (2018) series – in which he paints over photographic images of war-torn Beirut, experienced first-hand in 2006 – as an act of healing.

With the notion of difference and duality as an overarching, yet open-ended stratagem, Green circumvents the constrictions and potential hazards imposed by more prescriptive curatorial directives. As with any major survey exhibition, although viewers and commentators may query certain selections and (in this biennial) particular juxtapositions – consonant with a subjective and non-hierarchical curatorial approach – individual works are given sympathetic presentation and accorded generous space, avoiding the overcrowding that can often mar such surveys.

Writing recently in The Monthly, Miriam Cosic observed: “The Adelaide Biennial is overshadowed on the national art scene by the rich and heavily promoted Biennale of Sydney, which shows more than twice as many artists drawn from all over the world.” Certainly, the rescheduling of the Biennale of Sydney (in 2016 and 2018) from mid-year to March, not only invites direct comparisons, but also intensifies competition for media coverage, visitor numbers etc., albeit allowing international curators to attend both events. In his essay for Divided Worlds, Daniel Thomas makes the point that the Adelaide Biennial is lacking the additional “e”, in order to emulate the example of New York’s Whitney Biennial of contemporary American art and to distinguish it from “the Italian Internazionale Biennale.”

With its inaugural presentation in 1990, Adelaide’s Biennial of Australian Art – like the Biennale of Sydney – was programmed (in even calendar years) to alternate with Sydney’s Australian Perspecta, but also to synchronise with the Adelaide Festival of Arts. Following the demise of Perspecta in 1999, the Adelaide Biennial became the most enduring, and for a time the sole, recurring survey of contemporary Australian art. Increasingly, that position has become eroded, not only with the advent in 2016 of The National: New Australian Art (to be staged like Perspecta in alternating years with Sydney’s Biennale), but also later this year, Ballarat’s Biennale of Australian Art (BOAA) – promoted as “the largest visual arts festival showcasing [150] living Australian artists.” Comprehensive survey exhibitions with a more specific curatorial focus include AGSA’s recurring and highly successful TARNANTHI festival of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander Art (2015–), the National Gallery of Australia’s National Indigenous Art Triennial (2007–), as well as other one-off surveys (with gendered, racial or regional frames of reference) that underscore the growing slipperiness of blanket terms, such as “national” or “Australian.”

With the expansion of the 2018 Adelaide Biennial into four additional venues (including the Samstag Museum), the programming of three (discrete) satellite exhibitions and the participation of co-artistic directors Rachel Healy and Neil Armfield at exhibition launches, the visual arts had a more pervasive presence than in some past years. Since 2017, Healy and Armfield have delivered festival programs, which revive memories of the bold, sometimes challenging selections that historically defined the Adelaide Festival; their contracts have now been extended until 2021 (totalling an unprecedented continuous directorship of five festivals). With the concomitant opportunity for forward planning, is there then hope for further enhanced visual arts content and perhaps even the inclusion of a commemorative edition of Artists Week to coincide with the festival’s sixtieth anniversary in 2020?