For over sixty years, the practice of California-based artist John Baldessari has cultivated a distinct humour and irreverence, his art consistently employing a use of language that is equal parts poetic word-play and non sequitur. This interest in oddly defining juxtapositions broadly connects the artist to the conceptual art movement, but Baldessari also has a strong connection to art education, and from the 1950s has taught at all levels of education from preschool to university. Famously, his short Class Assignments (1970) prompted students with simple and amusing written instructions, which if enacted upon could expand in any direction. It is this sense of expansion that comes to the fore in Baldessari’s recent exhibition at the Monash Art Design and Architecture (MADA) Faculty Gallery, Wall Painting (2017). This work reflects on globalised curatorial practices while retaining the conceptual and pedagogical form of the earlier Class Assignments.

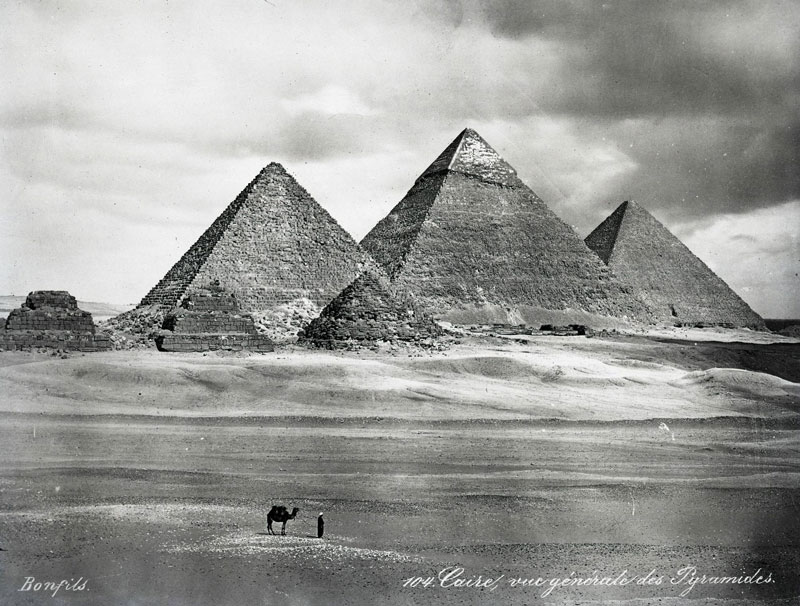

In a 2007 interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Baldessari described an unrealised artwork. The idea was for a different painter to each day paint the same wall a different colour, and afterwards hang up a small black and white photograph of the Egyptian pyramids in the centre of the wall. Baldessari thought it would be interesting to compare the two temporalities—the pyramids and the day-to-day transformation of the wall behind it. Tara McDowell, head of the curating program at MADA, wrote to Baldessari asking if she could realise this project at the newly opened faculty gallery. He accepted, but with otherwise minimal involvement, providing the idea and the image of the pyramids (its required printed dimensions).

For twenty-four days between October 7 and November 8, twenty-four students painted the back wall of the MADA faculty gallery a colour of their choosing. The commercially available colours had names like Capstan and Golden Marguerite. Employing the usual trappings of vernacular painting, the students used tarpaulins, rolls, brushes, extendable handles and ladders. They painted two coats throughout the day, allowing drying time in between, and only then would they re-hang the black and white image of the pyramids in the centre of the wall. During the painting and drying process, the photograph was leant against the wall, and the tarps, paint, rollers and such were left around the gallery.

The painters would “cut in” first—painting the corners and edges with a small brush—then, after painting the rest of the wall with a roller, they would leave the gallery and come back in a couple of hours to do the second coat. Small details and variations appeared throughout the process due to different competences, such as the layering of different colours accidentally marking the adjacent walls. The ladder presented a complication within the university setting, as OHS requirements meant each painter had to have an assistant present. The students weren’t permitted to work alone, and the roles between assistant and painter shifted and blurred, depending on the height, skill and the whim of those involved.

Wall Painting traces a line from conception to curatorial adoption, funding and implementation, well-exceeding the original simple idea expressed in three sentences in the interview. There is an obvious expansion in this investment due to the sheer amount of labour involved, supported by the available participants, venue and equipment at the school. In spite of the eagerness of the workforce, McDowell, wanted to avoid the ethical conundrums of employing students to provide free labour, so she arranged for each painter to be paid through funding from the United States Government alongside grants within the university. Drawn through a network of global dispersion, the generative idea for the artwork almost pales in insignificance beside the practical considerations of its realisation.

The flow of capital mirrors the flow of ideas, matching the investment of the individuated labour of the students. The work is perhaps best understood as a kind of pedagogical action akin to Baldessari’s I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art (1971). This earlier work—drawn from the Class Assignments—bears a strong resemblance to Wall Painting. Sent to Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax as a telegram in 1971, the instruction was for students to perform a kind of penance or mantra, by handwriting “I will not make any more boring art” onto the gallery wall for the duration of the exhibition.

While there are clear similarities between the two works, the issues have clearly shifted to prompt distilling down further the germ or matrix out of which action and practice can unfold. What are the implications of this in terms of distribution, authorship and intellectual property? Beyond the “dematerialised” conceptual practices of the early 1970s in which Baldessari participated, the emphasis is now on the capacity for following a set of rules or instructions. Now Baldessari is part of the post-conceptual canon. His proper name still presides over Wall Painting despite this hands-off approach. Yet this is not the whole story of the work.

The curator Tara McDowell, as the enabler of the “class activities”, is also acceding to the role of Baldessari’s student, or the player in a game of rules and instructions, not unlike the “Do It” project and strategy initiated by Obrist with the New-York based Independent Curators International. Baldessari becomes a kind of proto-globalised artist/curator, testifying to their shared concern with instruction- and rule-based economies of practice.

Wall Painting reflects on the shifting duality between Baldessari’s authorship as the project’s chief actor, and its many collaborators. This duality unfolds between the long-standing Giza Pyramids (representing Baldessari) and the daily reactivation of the wall’s colour (enacted by his student collaborators). These two temporal frames are manifest in the different kinds of labour and actions present in Wall Painting: the labour of the photograph, the labour of painting, the labour of the idea and the action of execution. Together, all these models of duration can be seen as a model for cinematic time, made manifest in the multiplication of the frame. If the twenty-four days are cinema’s twenty-four frames in a second, then what is revealed here is its practical unpacking or unfolding over time and place.

So what is MADA’s pedagogical aim in adopting Wall Painting as a project? There is certainly a practical outcome in the teaching and learning experience involving commitment, labour (of various outputs), finance and OHS. In terms of an art-historical outcome, students learned about John Baldessari’s practice as well as his approach to teaching. The 1970 Class Assignments were hung on the wall on sheets of A4 paper, and the activities facilitated teaching staff to turn the gallery into a classroom and site for “professional development” training. A notable aspect of this project is that it was hosted at a faculty gallery, metres away from the Monash University Museum of Art, playing on the relationship between the teaching or training faculty and the professional museum to also draw on the many innuendos of the labour market and careers in contemporary art.

There are many layers to this expansion of roles, repetitions, instructions and possible relational connections, although these are clearly limited to following a set of prescribed rules. While the instructional model leaves open the possibility for the generation of local differences and variations, the work ultimately sits tightly within the framework set by its author, who ultimately retains authority.