Regardless of the fact that Muslims have been in Australia since 1838 it is almost impossible to escape the shadows of incipient Islamophobia, exacerbated by media reports on the swarms of refugees on our doorstep about to irrevocably shift “our way of life.” In this alt-right climate We Are All Affected and The Invisible are great titles for exhibitions that feature the recent work of Australian Muslim artists. In both group shows, artists reveal aspects of their day-to-day experiences marked as separate, even dangerous within Australian and international culture because of their religion.

Both exhibitions also reveal the conundrums of art that engages with the immediate imperatives of politics. For over two centuries art has had no function, no clear utility – for example, it does not wash the dishes. In the 1980s there arose the notion that contemporary art exists as a form of philosophy, a space of social discourse to convey ideas about how we experience the world. Artists have become information providers, who have thoroughly digested postmodern theory and been made aware of the intricate power relationships that govern subjectivity and construct identity.

The challenge for the artists in We Are All Affected and The Invisible is how to translate and transcend their own memories, lived experiences and present realities for broader connection with audiences who I would suggest are largely already informed (albeit often erroneously) of the political and social contexts and concerns. How to combat racism in the face of intractable civil wars, aided and abetted by complicit external forces, physical and psychological violence and trauma, human rights versus human warehousing etc. Another challenge for artists who are advocates for causes is the miasma of issue fatigue and nostalgia, which swirls around difficult content, compounded by weary postcolonial artistic strategies such as the hyperbolising of traditional craft skills and debates around autobiographical reportage.

The work on exhibition in The Invisible was a fine example of the limitations of art as advocacy. The shopfront style UTS gallery had a hard-shiny glamour somewhat at odds with much of the content of the work gathered together by the participating artist and curator Abdul Kharim Hekmat. Featuring painting, photography, sculpture and video the essentialist focus of the exhibition explored the plight of Hazara and Kurdish peoples in their homelands and as refugees in Australia. I have to take issue with the curator, who states in the catalogue essay that they are “two of the worlds most persecuted ethnic groups” – a glaring editorial oversight if ever there was one. There is a long list of peoples who might also fit that claim: Australian Indigenous peoples, Palestinians, the Rohingya, Sudanese Christians, campesinos South American Indigenous peoples, ethnic Germans of the Ukraine et al. At least the refugee artists in this Australian exhibition have gained the freedom of agency and self-determination to register their views.

Untitled (from the The Arrivals series) (2016), a painting by Khadim Ali, operates as a somewhat illustrative signpost of cultural displacement. This out-of-scale Islamic miniature, full of pleasing archaic illusionistic technique, depicts a stylised seventeenth-century barque packed with approximately forty hybrid goat/donkey/demon creatures wearing red life jackets. The creatures are a composite of recent images of the Taliban who often call themselves the “Rustam of Islam” and the various demons that appear in the heroic tale of the Shahnama, The Book of Kings. In the stormy seas are empty life jackets and lifesavers plus assorted chimerical sea creatures, signs of imminent danger and tragedy, the now familiar backdrop to the bid for safe harbour.

Australia hosts the largest Hazara immigrant communities in the world. From the late nineteenth century there has been a deliberate policy to rid Afghanistan of the Hazara. Although resident in Afghanistan for over eight centuries, the Hazara people are not considered true Afghani by the Pashtun majority because of their Shia Islam faith and their distinctly different Mongol/Tibetan/Turkic physicality. As a Hazara refugee in Iran, Pakistan and Australia, Khadim Ali has a keen awareness of being cast or labelled as a demon. He is also a Trustee of the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

There are approximately 7,000 Australian Kurds. The Kurds are a people whose traditional lands sit across the present-day states of Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria. Literally homeland-less, they are among the many losers of the Sykes-Picot Agreement (made public 27 November 1917) which carved up the Ottoman Empire in the middle east between WWI victors, Britain and France.

Articulating the central gallery floor, Awan Anwar laid a grid of coiled and rolled blackened silver foil. Looking both slightly dangerous and decorative, at first I thought Displacement (2016) was a reference to thankfully now-diffused Improvised Explosive Devices. Rather, this work and Dancing Letters (2015) – an elegant black and white waterfall of cut paper shapes – are actually large-scale calligraphy symbols from poems by the nineteenth-century Kurdish poet Nali. These sculptures talk to the yearning that diaspora creates, as well as to contained and secret communications around lost languages and homelands.

Elyas Alavi also has two works in the exhibition. Fading Faces (2017) is an installation of thirty-three glass panels of loosely painted portraits of women and children from refugee camps. Ironically, at odds with the title of the work, the faces and bodies keep returning to consciousness as the lighting on the acrylic paint casts shadows between the glass and the wall to eerily animate the work. The intersections of fatalism, racism, mortality and memory are inescapable elements in the video installation Mohammed Jan (2016–17). This work documents the immediate effects of the death of a 14-year-old boy, one of ninety dead and four hundred injured in a July 2016 suicide attack at a Hazara demonstration in Kabul against the diversion of electricity from Bamiyan Province. Alavi places the video monitor low on the wall. This display technique not only physically demands that the viewer bow down and submit to the image but psychically hurtles us into the humble domestic environment where shocked brothers and sisters stare blankly while bewildered and angry parents speak to the camera about the death of their son. “Are we not from Afghanistan?” they ask. Mohammed’s favourite soccer jersey hangs beside the monitor.

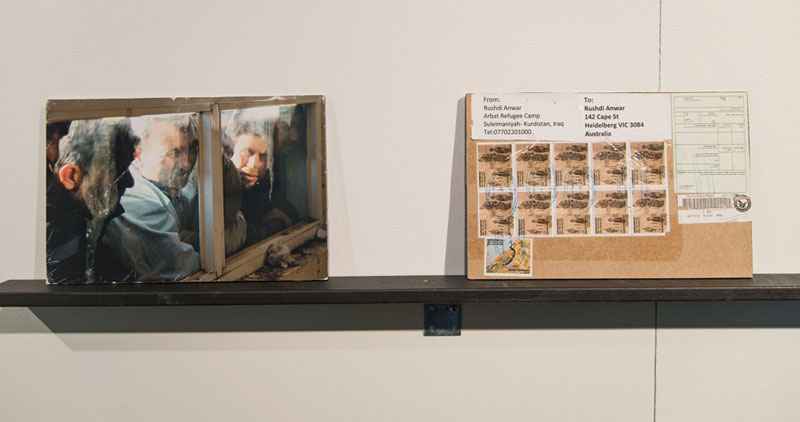

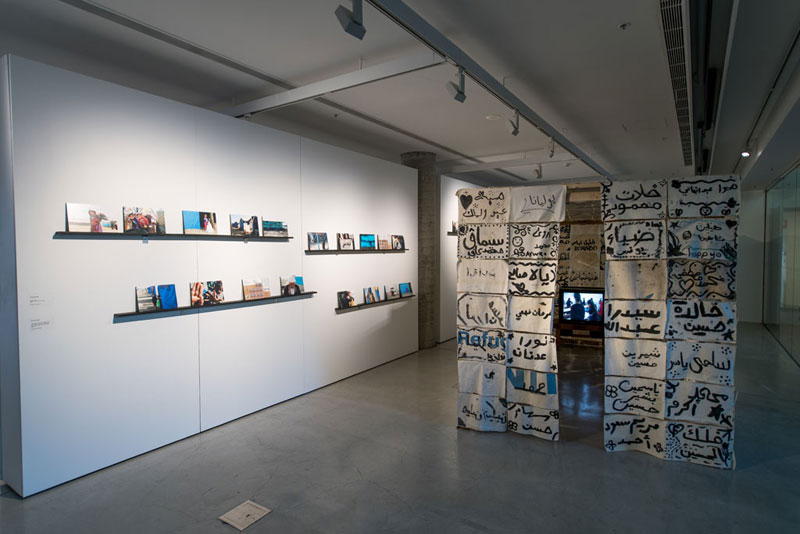

The sometimes-desperate life of young adults and children at home and in refugee camps are meant to be a revelatory focus of the exhibition. Abdul Kharim Hekmat has made three short soundscapes featuring the voices of refugees on Nauru. Rushdi Anwar presents two works, Unprotected an installation of large-scale postcard portraits of Kurdish refugees in Arbat Refugee Camp Suleimaniyah–Kurdistan Iraq. Close by, a flimsy rectangular structure composed of sections of UNHCR tents on which child refugees have written their names. Titled The Notion of Place and Displacement, inside the temple/mausoleum-like structure is a single monitor documenting the process of gaining the autographs.

We Are All Affected was co-curated by Khaled Sabsabi and Nur Shkembi who claim that we (they) exist in a constant “state of othering.” Opened during the Multicultural Eid Festival in July 2017 this was an exhibition across two venues, Fairfield City Museum and Gallery and Peacock Gallery, Auburn. At the latter, over a number of weekends, pop-up exhibits of photography, video installations, sculptures and ceramics were made more accessible and more real by the presence of the artists and curators who actively engaged in discussions across a range of public forums, talks and readings. These encounters with the general public were then documented and included at the Fairfield Museum, which itself revealed the shared curiosity and joy of discovery amongst audience members.

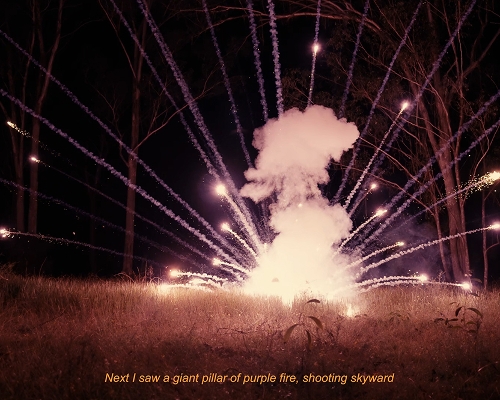

For me, the curatorial coup was to introduce members of the Sydney Islamic community to aspects of contemporary art and the people who make it in a comfortable, accessible venue within a broader celebratory cultural frame. Not that all of the art chosen for the exhibition was easy. Abdullah M.I. Siyed exhibited some images from the performative Soft Target series. The lens is placed at a vantage point above and behind the figure of the artist, who faces iconic structures in locations like Sydney, Dubai and New York. With his back to the viewer, he is framed and pin-pointed by the industrial colours of a portable fabric/plastic target, while adopting a tense expectant posture derived from Sufi zikr (dhikr) as reverent meditative acts of remembrance. These photographs are thought-provoking. What or whom is the target? Is this a representation of the artist as conduit for the Rapture, the End of Days?

Similarly perplexing was M.I. Siyed’s interactive performance work presented at the Auburn festival. One wonders whether the young children bursting balloons filled with a new US dollar note, while standing upon the target symbol featured in his photographs, did actually reflect on a world where “anxiety tends to lead to peril rather than pleasurable reward,” as stated in the catalogue essay Nur Shkembi and Eugenia Flynn. As part of the The Big Anxiety Festival, a Sydney-wide festival organised through the University of NSW, it certainly straddled the line-up of awkward conversations and mood experiments.

A more succesful engagement with contemporary identity politics and the colonising and corrupting forces of late capitalism was the video installation Whirl (2015) by Cigdem Aydemir. Displayed at both venues, Aydemir employs the tropes of television shampoo commercials of the last twenty years not only as a wry response to the fact that many Muslim women now actively participate in what has become known as “Pious Fashion” (as discussed by Elizabeth Bucar in her recent book on this topic, published by Harvard University Press), but also simultaneously to question the generally non-Muslim assumptions around the hijab as unveiled/liberated/beautiful and veiled/oppressed/abject, among a number of conditions listed in the catalogue.

Isolated in a cramped but historically significant building We Are All Affected at the Fairfield City Museum and Gallery featured familiar works by Abdul Abdullah and Abdul Rahman Abdullah. The Wedding (Conspiracy to Commit) (2015) and Wednesday’s Child (2013) show opposite representations of childhood and cultural difference. The former, a lurid Pierre et Giles-like tableau featuring a balaclava-clad wedding couple to destabilise and make perverse a comforting tradition is underlined with education and knowledge presented as light, a gift from the divine. Also on display were poignant homages to the strength and survival instincts of Somali women by Idil Abdullahi. She presented a series of stylised photographs and ceramic forms. The images depict text by the Somali poet and activist Hawa Jibril (1920–2011) while the ceramics were reminiscent of the goddess figures of Neolithic Bactria/Margiana.

Both exhibitions would have benefited from a recognition that we are all damaged goods, accidents of history. Indeed, it has long been argued that post 9/11 that we are outside of history, and such conceptualising is not a straitjacket but a liberating force. It is 2017, the curators and artists could be more keenly aware of the limitations of the strategies of witnessing and agitprop didacticism. Too much preaching, plaintive tones, distilled poignant moments overlaid with anger engenders resistance. I feel simultaneously annoyed and powerless encountering this type of tunnel vision art. But then perhaps this response, this striking affect is a mark of the continued currency of such content and indeed the success of these two intriguing exhibitions.