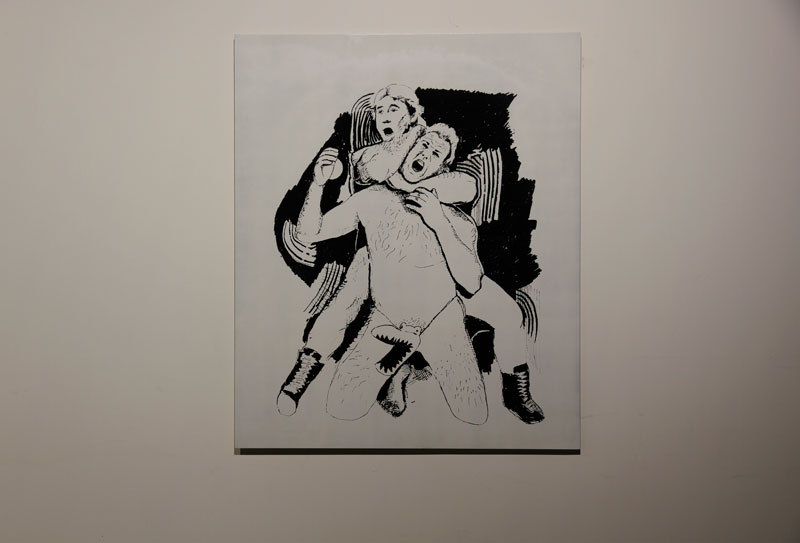

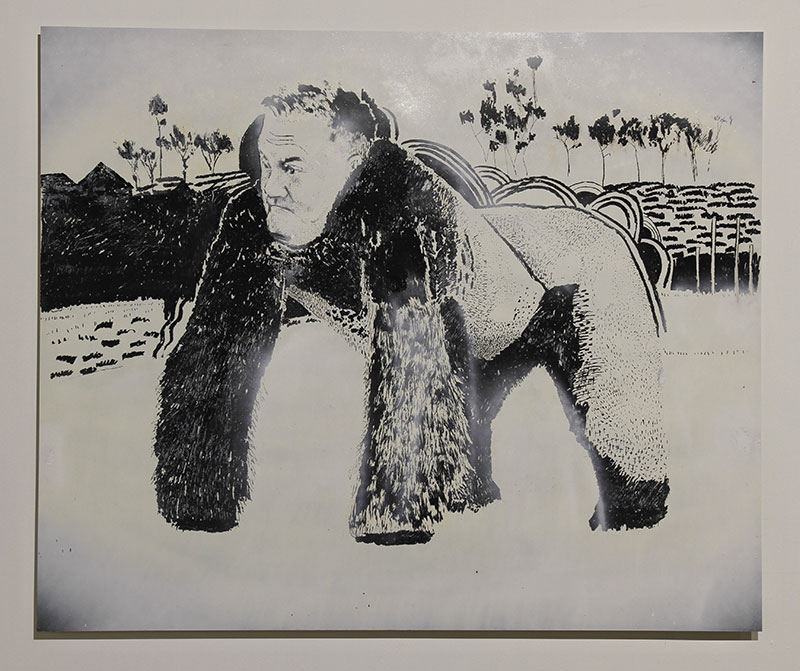

Sharks and Shamans is a powerful and irreverent collection of works by the contemporary interdisciplinary artists John “Prince” Siddon and Wes Maselli at PS Art Space in Fremantle. Opening between the state-sanctioned “Australia Day” and Fremantle’s own “One Day In Fremantle” – held on the 28th of January, to equal measures of local support and frenzied conservative backlash. Embracing this clash head on, Siddon and Maselli’s mixed media works open up a space to question the ideological power of seriousness and sanctimoniousness in white Australian politics and culture. Put simply, Siddon and Maselli’s works move between playful vibrancy – embodied in the dazzling colour and pattern-work of their etchings, carvings, and painted found objects – and a caustic humour that undermines complacency. Siddon’s carved and painted wooden figures radiate in the dim glow of PSAS, revealing the charisma of his animal and human subjects. Maselli’s etchings on tin are provocative, sending-up prominent white Australian figures – including Malcolm Turnbull, Steve Irwin, Shane Warne, and the “honorary aussies” Tim and Neil Finn. Two scathing and hilarious works of etched acrylic on tin by Maselli stand out: Eddie the Ape – representing the body of a Gorilla with the head of Eddie McGuire, replete with an ambivalent rictus smile; and the Kartiya diptych, showing a violent grapple between the two white fellas (Kartiya), Steve Irwin and Shane Warne, that is arresting in its comedic brilliance.

But is this a time for ribald jokes and vibrancy? In Australia, like the rest of the world, the march of nationalism, conservatism, and fascism appears to have only intensified. For many, at a time when the Hansons, Trumps, Le Pens, and Farages of the world appear horrifically emboldened, acerbic wit and vibrant beauty can only serve as dangerous forms of catharsis. For some, parody and vibrancy may seem to be mere distractions from a more conventionally political art; one that might, on face value, seem more appropriate for our present political and cultural situation. Arguably, what is important about the work of artists like Siddon and Maselli is this capacity to interrupt the political self-righteousness, and the disempowering injunction to be authentic that is so often fostered by the political establishment. Indeed, the playful and parodic elements of Sharks and Shamans speak equally to the importance of rejecting the strictures of imposed significance, especially when it emerges from a hegemonic culture, such as that of white Australia. As the contemporary theorist Elizabeth Povinelli argues in The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism, indigenous Australians are almost intractably caught between the demands to accept a white vision of Australia’s future and the imperative to conduct themselves in accordance with a state-sanctioned sense of what it means to be indigenous. The demand that indigenous people forget the past, and embrace a white neoliberal future, is combined with the expectation that indigenous people show themselves to be “proper” and “authentic” custodians of a culture over-determined by white history and anthropology. Such a demand to be good contemporary consumers, while also making manifest the pre-capitalism of indigenous culture is wonderfully exposed in Maselli’s “Bush Medicine” etchings – pieces that reveal the market underpinnings of the Western embrace of indigenous knowledge as a means of finding lucrative “super foods.” Similarly, Siddon’s depictions of animals – and especially those of sharks, an animal with a precarious status in many parts of Australia – raise questions about the liberal fantasy of a “melting pot” of ideas by combing celebrated indigenous artistic traditions with totemic embodiments of Western anxiety.

Indeed, if there is a principal target of Maselli and Siddon’s critique it is this sentimental and earnest attachment white hegemony has to the promotion and protection of its own institutions. No matter the number of clownish white politicians the public – and especially indigenous Australians – have to endure, the injunction is to take positions of office seriously, to tolerate the legal and political status quo without question. Indeed, recent clashes between the media, government, police, and protesters over the proposed destruction of the Beeliar wetlands – only twenty minutes from PSAS by car – shows the extent to which all opposition is crushed. Indeed, as the Beeliar wetlands of Western Australia move closer and closer to destruction, the public is told by politicians and the media alike that those who protest or dissent simply aren’t serious, they’re professional trouble makers, and should they find themselves on the wrong side of the law it’s their own fault. Protestors are routinely accused of being jobless and feckless. Those that question the imposed vision of our country’s future “don’t live in the real world” and are simply unwilling to face the “realities” propagated by the conservative media and government. To paraphrase the late great Niall Lucy, writing on the Chaser’s APEC stunt in Sydney in 2007, what the establishment fears is the possibility that humour and parody might capture the public attention and reveal the pretensions behind the demand to seriously respect established figures and institutions.

This association of propriety with moral superiority is of course a common method of downplaying the concerns of indigenous people and those that sympathise with them. When some protest the booing of Adam Goodes, the dismissal of indigenous culture and knowledge as a “lifestyle choice,” or the destruction of sacred indigenous sites, the answer from establishment politicians and media – and, it must be said, much of mainstream society – is to “get real” and “be serious.” After all, there are economic interests and “real injustices” that need consideration. The dismissal of alternative views or concerns as mere frivolities relies upon a clear distinction between what is admissible within discourse, and what is simply taking the piss. But to return to Lucy, to take the piss is to “mock authority, poking fun especially at its self-importance and always – always – with a straight face.” The emphasis for Lucy here is on playfulness. Moreover, by keeping a poker face those implicated by the joke are forced to seriously question their identity, so often taken for granted and reified, but also potentially disrupted by just such a gesture. This sense of taking the piss, perfectly embodied by Siddon and Maselli’s work, doesn’t let the viewer off the hook. The question that Siddon and Maselli’s work provokes is “how is the decision of what and who gets taken seriously made?” If, looking at an etching of Eddie McGuire’s grimacing poe-face fixed atop an ape, one were to wonder “is this a joke?” that would be asking precisely the right question. (McGuire was the prominent AFL mogul who likened Adam Goodes to King Kong.)

What is so powerful about Sharks and Shamans is this dual capacity to entrance the viewer and challenge notions of authenticity and good taste that allow so much art to be accepted on totally apolitical terms. Gazing at a semi-naked Shane Warne held in a chokehold by Steve Irwin I was struck by how absurd white Australian culture can be, and how absurd it is that we so often take the collection of stories and roles that make up Australia to be immutable and beyond reproach. Indeed, as curator Emilia Galatis and guest speaker Glenn Iseger-Pilkington posed the question to the audience on the opening night, “what does Australia mean to us today?” I couldn’t help but feel directed towards the possibility that Australia is something of a joke. This isn’t to say that Australia’s history and culture is all laughs and giggles, but instead to point out that Australia – that is, to say, the story of a place that is meant to unify us – like any joke, is something that has to be shared between people and cannot have one form or mode of delivery, but can only work when it finds an accord between those that share it. It is also worth remembering that our attachment to this story of Australia, like any joke, can be dangerous if taken too seriously.