The old language of alchemy is a heady mix of allegory, code and conjecture spanning many centuries of experiment in the arts and sciences. Forging links between natural, supernatural, divine and human forces, the old alchemists generated alternative logics to understand the cycles and systems of the universe. The appeal of such activity lay in the promise of transforming the ordinary into the valuable and the hope of finding the ultimate key – the philosopher’s stone – to come to an ultimate understanding of the sustainability of life.

This expansive exhibition curated by Alicia King for the Salamanca Arts Centre, retains the universal breadth of old alchemy, while adding to it a hefty dose of critique stemming from her concern for “an ever growing disconnect between our experience of the natural world and our internal conceptualisation of it”. King critically frames New Alchemists around the shift away from life as bare material to a view of progress through the impact of anthropocentric advances in science and technology. Beginning her catalogue essay with an alarming reference to the Junior Oxford Dictionary’s recent move to replace some biological words with technological terms, the show puts our increasingly technologised connection to life under scrutiny. The influence of King’s own artistic practice in the bio-material field can be felt in her gentle handling of the ebb and flow of consciousness through concepts of futility and productivity, hope and failure, connection and isolation across the selection of works for this exhibition.

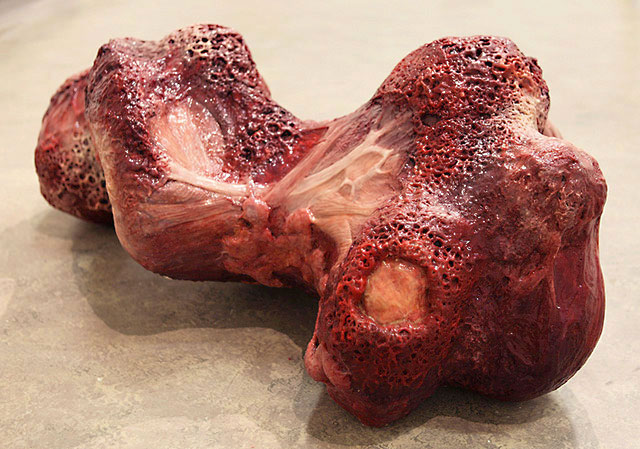

At the centre of this sprawling exhibition is, Ian Haig’s fleshy, ambiguous body Some Thing (2011). Appearing from a distance like the remains of a large animal, the work is an uneasy corporeal presence, unclassifiable in material and form. The isolation and uncertain definition of Haig’s work establishes the show’s conceptual frame, raising questions of biological evolution and experiment in the same breath. A self-contained mass of tendons, bones and skin, it is an object of abject horror reminding us of human corporeality and its potential alienation.

Contention around human–animal boundaries and the problem of classification lies at the heart of both Art Orienté Objet’s May the Horse Live in Me! (2011) and Thomas Thwaites’ I, Goat (2015). Although the works emerged from very different cultural contexts and methods, they both explore concepts of cross-species empathy and the potential permeability of biological boundaries. Art Orienté Objet’s May the Horse Live in Me! (2011) is a staging of bio-medical alchemy, showcasing the momentous event of artist Marion Laval-Jeantet being injected with horse blood in an act of cross-species transfusion and communication. The video of her performance, recorded in two parts as “in vitro” and “in vivo”, demonstrates current advances in bio-chemistry, creating a dramatic moment of biological realism as Marion’s body tolerates the normally intolerable foreign horse plasma. As Marion dons prosthetic horse legs and walks with the horse, the tension resolves to foretell a potentially transformative animal–human relationship.

Thomas Thwaites’s I, Goat (2015) is displayed as a series of photographic and video documents, with one of the sculptural contraptions Thwaites built in his attempt to live as a Swiss Alpine goat. This work is an enthralling, affectionate and at times amusing account of Thwaites’ exploration and ultimately thwarted becoming. It highlights the limitations of the human body in Thwaites’ attempt to overcome difference, reflecting an idealised empathy and union with the animal world. King’s juxtaposition of this and Art Orienté Objet’s work, builds a vision of the human body as a potentially productive but limited site of sustainable co-existence.

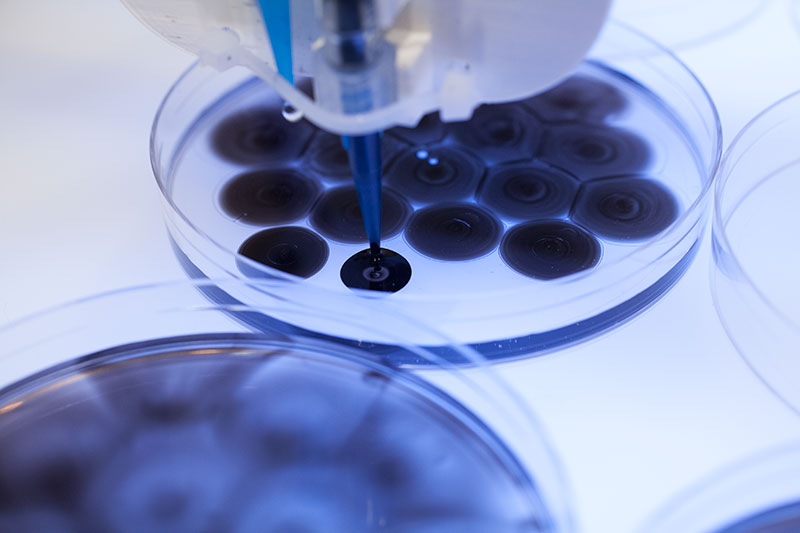

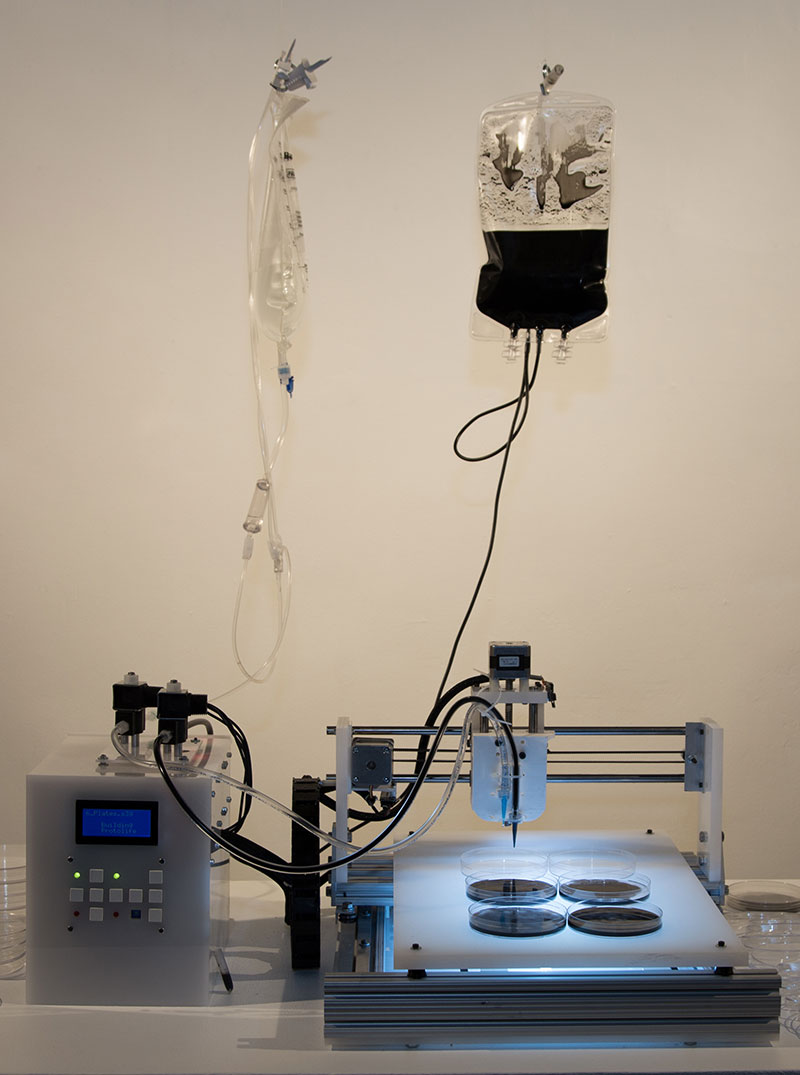

Further questions about the impact of bio-technologies on the human body are explored in Lu Yang’s video work Lu Yang Delusional Mandala (2015) and The Mechanism of Life – after Stéphane Leduc (2013) by Oron Catts, Ionat Zurr and Corrie Van Sice. Critiquing the definitions of life, according to the discursive mechanics of science, this work by Catts, Zurr and Sice explores recent developments in bio-engineering that rehearse early twentieth century attempts to position life as a purely chemical process, in reference to the theories of French biologist Stéphane Leduc. In what is effectively an aesthetic and technological conceit, the work’s custom-designed printer mimics the precise regularity of the lab instrument, creating cell-like droplets in a series of petri dishes. Comprised of chemicals and dyes, the “protocell” drops dissolve into a diffuse liquid alluding to what the artists suggest is a smokescreen of rhetoric promoted by today’s bio-printing industry around attempt to define life as pure process.

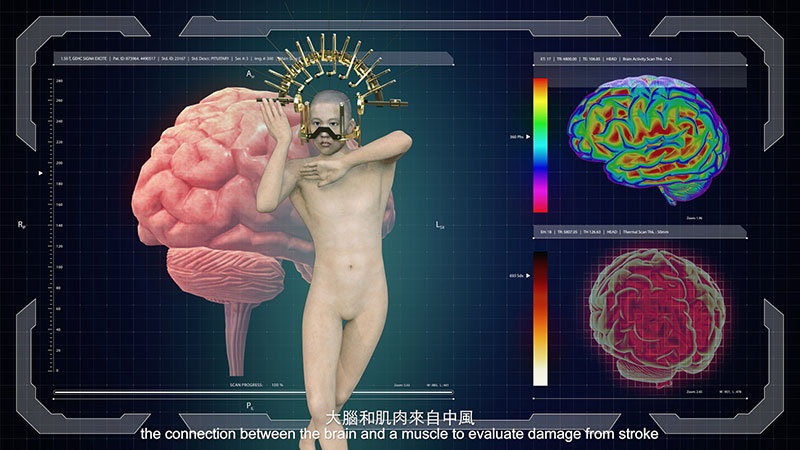

Where Catts, Zurr and Van Sice’s work plays with distinctions between “life” and the “lifelike”, the Lu Yang Delusional Mandala explores the concept that consciousness can be constructed and manipulated through neurological stimulation. Producing a self-image as a de-gendered, digitised body, Lu Yang approaches the question of consciousness through an imagined series of neurological manipulations where consciousness emerges as a technological construction. This work is also unsettling in its evocation of a delusional human endeavor as a concept of disconnection in extremis at our own expense. Overtones of a universal longing to escape the limitations of our human bodies is is also found here, but this time conceived as a form of bio-technological reverie supporting the idea that technology can relocate our consciousness in time and space.

Nadege Phillipe-Janon and Michaela Gleave present more environmentally focused works, in reflection upon the concept of an expanding universe that is both immediate and beyond our grasp in equal measure. In a separate gallery, Phillipe-Janon’s site-responsive installation Jerry on the Katabatic Wind (assisted by Bill Hart) draws directly on local data produced by a weather station positioned on the roof of the gallery. A microcosm of the elemental processeses of transformation and symbiosis, the work is an alchemical mix of mechanical and air-propelled ephemera, light projections creating reflections on water, rocks, crystals, plastic ephemera and organic detritus under perpetual stimulus. Reminding us of the interconnectivity of all things, Phillipe-Janon’s exquisite componentry offers a view of a unified system built on notions of dependency and fragility.

In contrast to the intimacy of Phillipe-Janon’s work, the eloquent stasis of Michaela Gleave’s works The World Arrives at Night (Star Printer) (2014) and We Are Made of Stardust (2011–12) is even more poignant. King reinforces the sense of distance embedded in Gleave’s works by positioning them at the far end of the gallery like a final frontier. There is a loneliness to the installation as the neon of We Are Made of Stardust shifts silently through its colour spectrum, and the dot matrix printer spews out astronomical data in an isolated, intermittent way. In relation to the other works in the show, Gleave’s works support an eerie absence of agency, a sense that our data has finally become debris, that the universe has abandoned us, or that something else we don’t know about yet is in charge. In such a mix of nostalgia and futuristic yearning, Gleave’s work suggests the kind of long-range perspective that exists in King’s vision too – is life just the sum of our constructions, or something beyond us, closer to the sublime?

All situated beautifully within a speculative realm, New Alchemists highlights the vulnerability of bodies at the limits of knowledge, the blindspots and glitches in our known universe to privilege the hopes and failures of the human experiment in an increasingly technologised world.